A lecture by Prof. Dr. Joseph Ratzinger, Tübingen.

- Joseph Ratzinger

Man’s ultimate battlefield is the Cross. In it, John Paul II looks for the reunion of the human person and society.

Was J.R.R. Tolkien a modern writer? The author of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion is undoubtedly “modern” in the sense that he lived in our own historical period (he died in 1973). Furthermore, his writing is extraordinarily popular with modern readers. But critics often allege that he was not modern but rather pre-modern in his approach to literature, and certainly they are right in the sense that it was ancient storytelling traditions and Anglo- Saxon literature such as Beowulf that particularly inspired him. His book contained many archaic elements. It was not, however, archaic or pre-modern in itself. The Lord of the Rings is a novel with modern concerns. It could not have been written in an earlier age. It contains an implicit but very strong critique of modernity – of aspects and tendencies of the modern world – such as globalization, socialism, and reliance on technology. But is this regressive or progressive? Only time will tell.

But first, who was this man, this writer? Like every one of us, he was more than the sum of his parts. As a child he became an orphan – his father died when he was four, his mother (a Catholic convert reduced to poverty by the resulting exclusion from her family) when he was twelve. Later he became an Oxford don, a professor of Anglo-Saxon. He worked on the Oxford English Dictionary. He translated the Book of Job for the Jerusalem Bible. He cycled to Mass nearly every day. In the evening he made up stories for his four children. People say he dressed up like an ancient warrior with horns on his head wielding a big axe to chase tourists out of his garden. He was a bit like an overgrown hobbit, with his fancy waistcoats and his pipes of tobacco. (In fact he once described himself as a “Hobbit in all but size.”) And he was very like a wizard in his old age, casting a magic spell with his words over millions of readers.

In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day and more than a million lives on both sides were lost altogether. The experience helped to make him a writer, as it did the war poets Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, and Siegfried Sassoon, and in the next war the fantasy writer T.H. White, author of The Once and Future King. In later years, looking back, Tolkien described how the early writings about Middle-earth and some of his made-up Elvish languages began as a distraction when he was supposed to be paying attention to being a good officer in the War: “in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle-light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire” (L. 66).1 He wrote fantasy, he said, in order to express his feelings about good and evil, fair and foul; to make sense of them, and prevent them “just festering.”

In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day and more than a million lives on both sides were lost altogether. The experience helped to make him a writer, as it did the war poets Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, and Siegfried Sassoon, and in the next war the fantasy writer T.H. White, author of The Once and Future King. In later years, looking back, Tolkien described how the early writings about Middle-earth and some of his made-up Elvish languages began as a distraction when he was supposed to be paying attention to being a good officer in the War: “in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle-light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire” (L. 66).1 He wrote fantasy, he said, in order to express his feelings about good and evil, fair and foul; to make sense of them, and prevent them “just festering.”

Another aspect of Tolkien might surprise you: Tolkien as Romantic Lover. He fell in love in 1909 at the age of sixteen with a pretty girl called Edith Bratt who was three years older than him, also an orphan, but a Protestant. His guardian by that time, the rather strict Father Francis Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory, forbade him to see or speak to her until he came of age at twenty-one, and he obeyed fairly well – except for a couple of clandestine meetings early on, which got him into trouble, and some accidental encounters later – with the result that by the time he finally wrote to ask her to marry him, on the evening of his twenty-first birthday, she had become engaged to someone else, thinking Tolkien had forgotten her. Luckily she was still in love with him and willing to break off the engagement. In 1914 she reluctantly converted to Catholicism (in those days mixed marriages were not permitted in a Catholic church), and in 1916 they married in the Church of Mary Immaculate in Warwick. Despite occasional tensions2 it was a remarkable lifelong romance, and left its mark on Tolkien’s writing in several ways.

If you have read The Lord of the Rings or seen the movie, you’ll remember the love story concerning Aragorn and Arwen. In Tolkien’s writing, this harks back to an earlier romance between Man and Elf, many thousands of years earlier – the story of Beren and Lúthien, the ancestors of both Aragorn and Arwen. Wandering in the summer in the woods of Neldoreth, he writes, the man Beren came upon Lúthien, the princess of the Elves,

at a time of evening under moonrise, as she danced upon the unfading grass in the glades beside Esgalduin. Then all memory of his pain departed from him, and he fell into an enchantment; for Lúthien was the most beautiful of all the Children of Ilúvatar [the Elvish name for God]. Blue was her raiment as the unclouded heaven, but her eyes were as grey as the starlit evening; her mantle was sewn with golden flowers, but her hair was as dark as the shadows of twilight. As the light upon the leaves of trees, as the voice of clear waters, as the stars above the mists of the world, such was her glory and her loveliness; and in her face was a shining light.

Beren falls instantly in love, and asks for her hand in marriage. Her father sends him on a seemingly impossible quest, in which (though only with Luthien’s help) he succeeds. Eventually, however, he is killed and she descends into the underworld to rescue his soul. She sings so beautifully to the Lord of the Dead that both are restored to life for a brief time. It is a beautiful story, right at the heart of Tolkien’s writing, but the romance he was describing was in a way his own – a kind of mythological statement about what it felt like to fall in love at first sight, how love can reshape one’s entire life, and how husband and wife achieve the Quest together or not at all. Tolkien and Edith are buried together in Oxford, and on their tombstone he had the names engraved of Beren and Lúthien.

Finally, of course, Tolkien was a master of languages. His friend C.S. Lewis, in an obituary, even wrote that Tolkien unlike other, more superficial linguists, had travelled “inside” language, like an explorer penetrating a barrier and finding a place no one else had been. He understood the music and the meaning of language, and the way it evolves through time, perhaps better than anyone else before or since. Already as a teenager he knew most of the main European languages, ancient and modern. In school debates he was happy to speak in Latin, Greek, Gothic, or Anglo-Saxon instead of English. Later he came to love Finnish and Welsh particularly.

And of course he soon started to make up new languages of his own, although he began to think of them not so much as inventions but as reconstructions of old languages that might have existed before the ones we know, going back to a mythological time before history, a time when elves and dragons walked the earth. Middleearth, you could say, was constructed partly as a setting for these languages – to imagine a world in which it would make sense that people spoke Elvish not English.

Each of the elements I have been describing in Tolkien’s make-up – soldier, lover, linguist, and Catholic – specifically contributed to his critique of modernity, and I will say a brief word about each in turn.

«In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day.»

«In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day.»

First, through fighting in the War he became very aware of the sudden onset of the modern age, marked by the use of weapons of mass destruction and the increasing mechanization of warfare – but at the same time he learned to appreciate the moral virtues of the ordinary English soldier alongside he was fighting, the English “tommy,” as he was called. In fact the character of the lovable, unpretentious, and yet indomitable working-class Sam Gamgee is a portrait of the men he got to know in the trenches of the Somme – a ruined landscape, by the way, which bore a marked resemblance to the Dead Marshes through which Frodo and Sam are led by Gollum on their way to the Black Gate of Mordor. His account of the Fall of the hidden Elvish city of Gondolin was begun at this time, and describes an assault by Orcs and Balrogs, “dragons of fire” and “serpents of bronze and iron”, under great steams and smokes that must have been partly inspired by his experiences on the Front. Later, The Lord of the Rings was written during the Second World War, in which his son Christopher served, a war fought against a great dictator who was seeking to bring the whole world under his dominion – and yet a war that was eventually won by the use of tactics and technology that Tolkien abhorred, for example the fire-bombing of Dresden and the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He calls it “the first War of the Machines”, which will leave everyone the poorer, millions dead, “and only one thing triumphant: the Machines” (L. 96). After the War, he prophesied, “the Machines are going to be enormously more powerful” – prompting him to ask: “What’s their next move?” (ibid.).

In his published Letters, Tolkien refers to the “tragedy and despair” of modern reliance on technology, when it alienates us from the natural world. In the novel, this tragedy is vividly illustrated in many ways, not least by the corrupted wizard Saruman, with his “mind of metal and wheels.” In the modern world, with its ecological disasters and its factory farms, we have seen the devastating and dehumanizing effects of Saruman’s purely pragmatic approach to nature. The English Romantic movement, from William Blake and Coleridge through to the Inklings, believed there must be an alternative. At the end of his wonderful essay The Abolition of Man, which everyone ought to read, Tolkien’s friend C.S. Lewis writes hopefully of a new kind of science, a “regenerate science” of the future that “would not do even to minerals and vegetables what modern science threatens to do to man himself. When it explained it would not explain away. When it spoke of the parts it would remember the whole.”

For modern science, on the other hand, Lewis argued, as for the old black magic that never really worked, the goal is power over the forces of nature. That power is sought for a variety of reasons, some good, some bad. We may wish to satisfy our curiosity and increase our knowledge of how the world works. We may wish to do wonderful things with our new-found power over nature: end poverty, extend life, heal disease. We may simply want to win a Nobel Prize. But what Lewis calls the “magician’s bargain” tells us what the price of such power may be: namely, our own souls. In fact, he says, the conquest of nature turns out to be our conquest by nature, that is to say, by our own desires or those of others (those who end up controlling the machinery). Only those who are masters of their desires, and not driven by them, can really be called powerful or free.

Tolkien explores two different types of technology, two different understandings of science, through the contrast in his story between the Elves and the Enemy: the science of the Elves (called “magic”) has not been separated from art as it is in our day; indeed, it could be called a form of art. If the goal of the Elves is Art, the aim of the Enemy is what he calls the “domination and tyrannous reforming of Creation.” The devices of the Elves, like the magic Ring worn by Galadriel to protect Lothlórien, are all more or less benign. They work “with the grain of nature,” not against it. The science of the Enemy, in Tolkien’s world, is very different. It reflects a desire to control. The will to power, he writes, “leads to the Machine”: by which he means the use of our talents or devices to bulldoze others into submission. The Ring of Power, the “One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them,” is an example of this kind of technology. And he is realistic when he shows the biggest temptation to use the Ring is felt by those who persuade themselves they want to do good rather than evil – to make the world a better place by bending it to their own will.

Of course, when we get into the task of “locating” the Ring, or what is left of it, in the present world, I should mention that Tolkien always insisted that his fantasy was no mere allegory. Mordor was not a thinly disguised Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia. He once wrote: “To ask if the orcs ‘are’ communists is to me as sensible as asking if communists are orcs.” But at the same time he did not deny that the story was “applicable” to contemporary affairs, indeed he affirmed this. It is applicable not merely in providing a parable to illustrate the danger of the Machine, but in showing the reasons for that danger: namely the ever-present vices of sloth and stupidity, pride, greed, folly and lust for power, all exemplified in the various races of Middle-earth.

This important lesson that Tolkien drew from the War –that evil must not be done for the sake of the good– has many important implications. Even the Orcs, who appear utterly evil and who “must be fought with the utmost severity,” Tolkien writes in one of his notebooks, “must not be dealt with in their own terms of cruelty and treachery. Captives must not be tormented, not even to discover information for the defence of the homes of Elves and Men. If any Orcs surrendered and asked for mercy, they must be granted it, even at a cost.” In recent years and months we have seen the British and American secret services put on trial for allegedly flouting this principle and torturing prisoners. Tolkien’s parable remains instructive on many levels.3

Earlier I said that Tolkien’s romance with Edith – his role as romantic lover – was itself a basis for his critique of modernity, and it is time to explain what I meant by that. Bear in mind that in writing these stories he was not constructing an “escape” from everyday reality, as critics allege by calling this kind of thing “escapist” literature. He was trying to show, albeit in an exaggerated and imaginary form, the way the world really works, both morally and spiritually. The actor who played Aragorn in the movie, Viggo Mortensen, when asked why the film and the book were so popular, replied that he thought it was because they tell a “true story.” He was right. There is truth in the story, and that is what makes it so interesting. But by building romance into the mythology the way he did – and this only becomes obvious when you read The Silmarillion as well as The Lord of the Rings – Tolkien was affirming that all of history is in the end a love story; that love is the most important thing in the world – it is not just what shapes the world, but the thing for the sake of which everything happens. Not just the love of man and woman, of course, but also the love of friends and the love of beauty and the love of life that comes to a kind of crescendo in the fruitful love of marriage.

Take The Lord of the Rings itself. Frodo’s Quest to destroy the Ring begins with his desire to save his beloved Shire from the Shadow that threatens to engulf it. It is the love of his friends that creates the Fellowship which achieves the Quest. Each member of the Fellowship plays a part. Through that adventure, the Hobbits grow up. They learn the virtues of courage and fidelity and wisdom that are needed to heal the Shire of the evil that infects it when they return. (Very unfortunately this part of the book was omitted in Peter Jackson’s film.) And Sam in particular – who is in a way the hero of the story, almost more than Frodo according to the author – acquires through these adventures the maturity and courage to propose to his beloved Rosie, and settles into Bag End as Frodo’s heir, before long with a big family. The Lord of the Rings ends with his return from the Grey Havens:

And he went on, and there was yellow light, and fire within; and the evening meal was ready, and he was expected. And Rose drew him in, and set him in his chair, and put little Elanor upon his lap. He drew a deep breath. “Well, I’m back,” he said.

With this ending, Tolkien was making the point that all the high epic adventures in Rohan and Gondor and Ithilien, all the battles and torments that the Hobbits had gone through at the hands of the Orcs and on the fields of the Pelennor, were for the sake of the Shire, to enable the Hobbits not only to defend and heal it, but in the case of Sam, to settle down into ordinary domestic life.

The Shire, of course, represents the England that Tolkien loved, the villages and fields that he played in as a child, and the horrible slum ruled by Saruman that they find on their return is a vision of what modernity has done to that English idyll 4. You could say that the lesson of the story is that ordinary life, and especially marriage and family today, needs to be protected and supported not just by external armies but from within, by a life of heroic virtue, or by virtues that would be recognized as heroic if projected onto the big screen of an adventure far from home, because there they can be seen for what they really are.

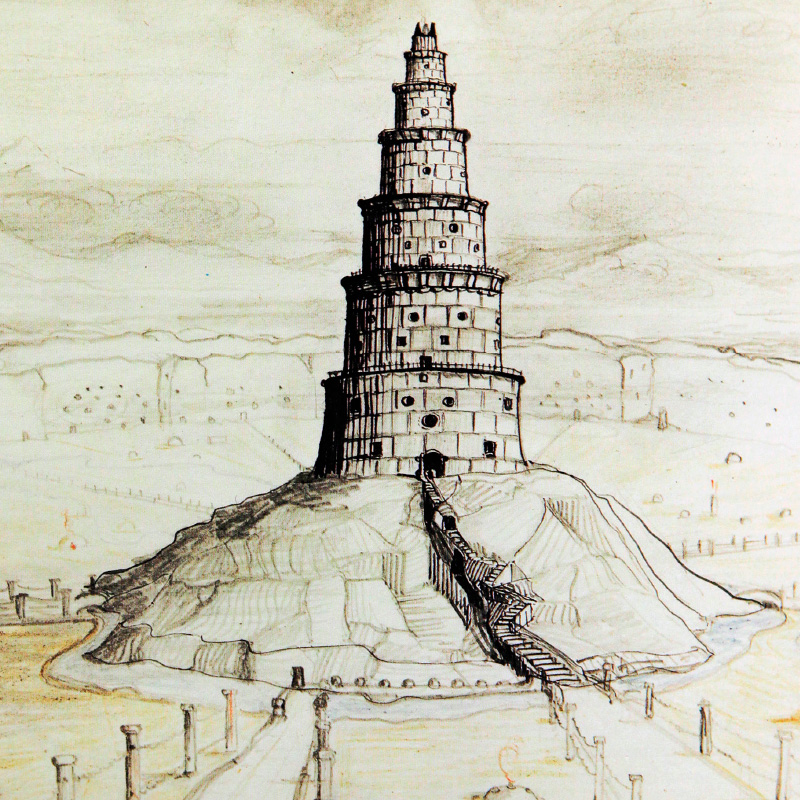

«In his published Letters, Tolkien refers to the “tragedy and despair” of modern reliance on technology, when it alienates us from the natural world. In the novel, this tragedy is vividly illustrated in many ways, not least by the corrupted wizard Saruman, with his “mind of metal and wheels.”» Tolkien’s drawing of the Tower of Isengard (Orthanc).

«In his published Letters, Tolkien refers to the “tragedy and despair” of modern reliance on technology, when it alienates us from the natural world. In the novel, this tragedy is vividly illustrated in many ways, not least by the corrupted wizard Saruman, with his “mind of metal and wheels.”» Tolkien’s drawing of the Tower of Isengard (Orthanc).

As for Tolkien’s love of language as a source for his anti-modernity, it is bound up with his love of tradition, of history, and of folklore. The evolution of languages cannot be separated from the evolution of civilizations, and the words we use today give us clues to things that happened, and the way people thought and acted in the distant past. Tolkien wanted to unravel language, and travel back through time to see a lost world, one that predated the histories known to us, so far back that it would appear mythological, enabling him to speak of mysteries such as creation itself, and the origin of good and evil, and the obscure longing that haunts us for a paradise we somehow feel once existed on the earth. “We all long for it,” he wrote (L. 96), “and we are constantly glimpsing it: our whole nature at its best and least corrupted, its gentlest and most humane, is still soaked with the sense of exile.” The sense of longing, of nostalgia for paradise, comes (he thought) from the best part of ourselves, the part that “remembers” its Origin, when we came from the hand of God and were first filled with the breath of life. He was “anti-modern” in the sense that modernity often stands against this kind of yearning with a kind of world-weary cynicism. Such things never were, we are told, and never could be because Man is just an animal like any other, except nastier and more dangerous. Tolkien’s stories say, No! We can look up at the stars, we can aspire to be greater than we are, and if we do this then divine grace will help us. Our very ability to imagine worlds like Middle-earth and the Blessed Lands of the West prove that we are more than these modern cynics choose to believe. In a poem called “Mythopoeia,” inspired by a conversation with C.S. Lewis that led to Lewis’s conversion to Christianity, he summed it up like this:

The heart of Man is not compound of lies, but draws some wisdom from the only Wise, and still recalls him. Though now long estranged, Man is not wholly lost nor wholly changed. Dis-graced he may be, yet is not dethroned, and keeps the rags of lordship once he owned, his world-dominion by creative act: not his to worship the great Artefact, Man, Sub-creator, the refracted light through whom is splintered from a single White to many hues, and endlessly combined in living shapes that move from mind to mind. Though all the crannies of the world we filled with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build Gods and their houses out of dark and light, and sowed the seed of dragons, ‘twas our right (used or misused). The right has not decayed. We make still by the law in which we’re made.

Tolkien’s search for the Beginning of all things was expressed through the invention of mythology, but his desire for it was awoken by the love of language, or rather of the Word – the divine Logos, the Second Person of the Trinity – that he felt he could hear resounding like a kind of distant music in certain phrases in certain languages, such as Anglo-Saxon.5 It was this that in 1914 prompted him to start writing, and he never stopped until his death in 1973. His mythology expresses the very profound intuition that prose begins in poetry, and poetry in song, and song in music, and that music is equivalent to light, which is the primary vibration stirred by the voice of God in the deep waters of existence. So that all of history, like all of cosmology, is the unfolding story of Light and Music, in which God expresses his joy by giving freedom to creatures who sing and shine with him, and by bringing good out of the evil that seeks to engulf the light at every turn.

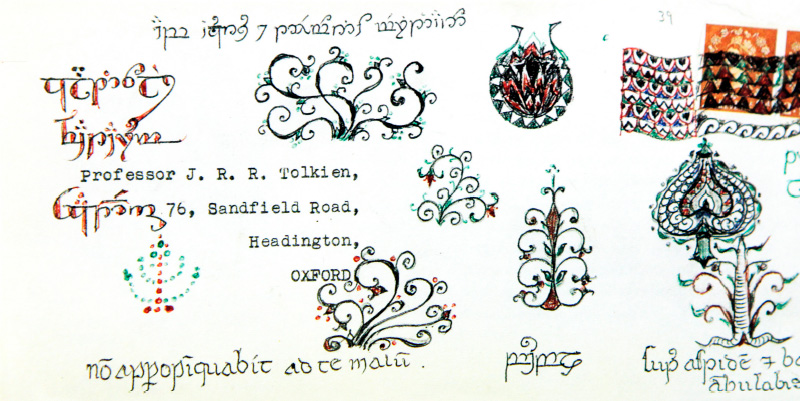

«He soon started to make up new languages of his own, although he began to think of them not so much as inventions but as reconstructions of old languages that might have existed before the ones we know, going back to a mythological time before history, a time when elves and dragons walked the earth.» Envelope with Tolkien´s elvish writing.

«He soon started to make up new languages of his own, although he began to think of them not so much as inventions but as reconstructions of old languages that might have existed before the ones we know, going back to a mythological time before history, a time when elves and dragons walked the earth.» Envelope with Tolkien´s elvish writing.

And so we come to the fourth and final point, Tolkien’s Catholicism. How much more anti-modern can you get, than to be a Roman Catholic? Or rather, to be a Catholic of Tolkien’s kind, traditional and orthodox and devout, in the end submissive to Rome even when it changed the liturgy he loved, faithfully upholding the supreme value of the Real Presence (L. 250), and even the unpopular teaching on marriage? Of course, The Lord of the Rings makes no reference to religion, and is even less obviously a Christian work than C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. Nevertheless, in 1953 Tolkien admitted to a Jesuit friend, Robert Murray, that “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision” (L. 142). He goes on to say that he has nevertheless cut out “practically all references to anything like ‘religion,’ to cults or practices, in the imaginary world.” He has done this so that “the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.”

But he did leave some clues. The calendar date he gives for the destruction of the Ring is March 25th, which in “the real world” is the Feast of the Annunciation, the day on which Catholics celebrate the beginning of the Incarnation in Mary’s womb.6 Mary was preserved from sin, and strengthened in her will to good, by the grace that flowed into the world (both backwards and forwards in time) from the Cross. Her Yes to the Holy Spirit was therefore the beginning of the final reply to Sauron, and the definitive rejection of the Ring. (In fact there is a longstanding tradition that the Crucifixion also took place on March 25th.) And clearly aspects of Christ and his mission are glimpsed at various points in The Lord of the Rings, for example when Aragorn walks the Paths of the Dead and returns to claim his throne, and when Gandalf gives his life to slay the Balrog in Moria and is “sent back” to Middle-earth in resurrected form as Gandalf the White, endowed with new authority. Frodo and Sam’s journey across Mordor and up the side of Mount Doom carrying the Ring is very reminiscent of Christ’s stumbling walk to Calvary carrying his Cross. In these and other ways, one can tell that Tolkien believes in Christ and also believes that the mission of Christ is bound to send out echoes and reflections throughout human history and mythology.

But these references to Christianity are buried very deep, and one does not have to notice them in order to enjoy the book for its own sake (it is, after all, set in a pre-Christian time). What is more important, and more obvious, is the moral universe that Tolkien portrays, a world of virtues, vices, and temptations. The vices are vividly portrayed in the Orcs and Saruman – greed, envy, pride, hatred, and so on – and in the case of Denethor, the Steward of Gondor, despair. Against these vices he sets the virtues of courage and courtesy, kindness and humility, generosity and wisdom, in the hearts of the Fellowship. And he shows how the human heart is often balanced between the two, as in the case of Boromir or Frodo, where the Ring serves to represent the ultimate temptation, the temptation to wield power over others.

I hope I have said enough to suggest some of the ways in which Tolkien can be called anti-modern. He was in many ways a part of the great Romantic movement in European literature. The Romantic poet William Blake also composed great mythological epics, as well as poetry, and criticized the scientific and industrial revolution for its dehumanizing effects on society. The Romantics believed less in Reason and Science than in Feeling and Imagination. Tolkien retained this belief in the importance of the Imagination, but unlike some of the Romantics he also believed in objective Truth, and as a Catholic he tried to integrate emotion and imagination together with rational thought into one comprehensive vision of reality.

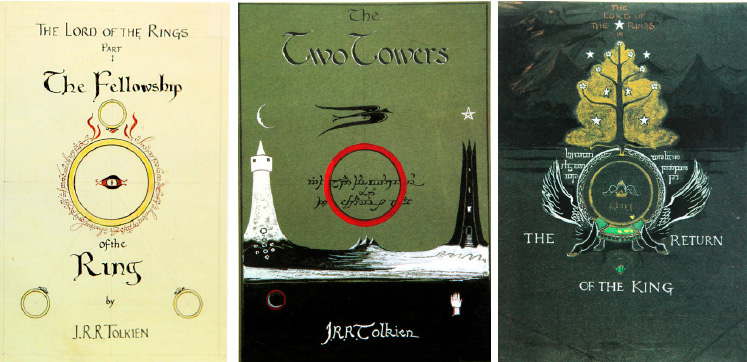

«He felt that the four members of the TCBS, with their refined sense of honor and poetry and beauty, “had been granted some spark of fire… that was destined to kindle a new light, or, what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world”.» Cover designs for the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings by Tolkien.

«He felt that the four members of the TCBS, with their refined sense of honor and poetry and beauty, “had been granted some spark of fire… that was destined to kindle a new light, or, what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world”.» Cover designs for the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings by Tolkien.

But this very fact makes him as much post-modern as anti-modern – or rather, if the term postmodern is associated with the last gasp of modernism and the “failure” of the Enlightenment, we might call people like Tolkien post-postmodern, because they are looking backwards in order to move forwards. As a schoolboy at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, Tolkien formed a close friendship with three other boys who together called themselves the TCBS (Tea Club and Barrovian Society). After they left school and went on to Oxford and Cambridge, and then into the Army to fight in the War, they remained friends. It was through them on the eve of the War that Tolkien found in 1914 his sense of his vocation as a writer. He believed that the TCBS “was destined to testify to God and Truth in a more direct way even than by laying down its several lives in this war” – in a work that may be done “by three or two or one survivor,” always inspired in part by the others. Tolkien, of course, was one of the survivors.

He felt that the four members of the TCBS, with their refined sense of honor and poetry and beauty, “had been granted some spark of fire… that was destined to kindle a new light, or, what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world” (L. 5). Do you see what I mean? The “old light” that they wanted to bring back into the world is the light of beauty and of truth grasped by the Romantic imagination, a beauty of poetry and art and a love of nature that was fast being eliminated by consumerism and mass media, by the noise and pollution and technology that is spreading everywhere. But this is the same as a “new light,” because in a very real sense it is timeless, and by perceiving it we begin to create a new civilization based on a different set of values.

I believe, and I think Tolkien secretly believed, that by writing his stories he had constructed a literary vehicle in which to transmit the vision of the TCBS to the wider world. He had given millions a glimpse of the “old light” of beauty and truth, and for those who allow this light to get into their souls, nothing is ever quite the same again.

In this brief space it is impossible to do justice to all the themes developed in this monumental encyclical, whose purpose is to update Paul VI’s encyclical, Populorum Progressio, after more than forty years since its publication, which is considered by the current Pontiff as the Rerum Novarum of the contemporary epoch (n. 8). Therefore, I will abide by its novelty, taking as reference basically paragraph 70 of the encyclical, which is in chapter VI, “The development of peoples and technology.”

Paul VI’s statement that authentic development had to be of “the whole man and of all men” has become became very wellknown. This statement, which Benedict XVI endorses and now explains in the new historical context of the development problem, has two dimensions. The expression “the whole man” refers to the foundation; that is to say, to the truth of man, to his transcendent dimension, spiritual condition, and above all, his vocation for eternity. From this point of view, the encyclical states that “Paul VI taught that progress, in its origin and essence, is first and foremost a vocation” (n. 16), which means, on the one hand, the answer to a transcendent call from the Creator himself, and that, therefore, progress cannot take an ultimate meaning by itself. On the other hand, such an answer requires freedom and responsibility (n. 17). As he has done so many times, this is a clear invitation from the Pope to expand reason and our horizon, also in relation with current social realities. The “all men” expression has as its historical horizon the growing interdependence of the people, which at the end of the sixties was beginning to become evident, and forty years later, continues to be so evident that the Pope calls it an “explosion of worldwide interdependence, commonly known as globalization” (n. 33). Then, the horizon of justice and peace exceeds the boundaries of local political power and national states, to consider this new form of relationship, which affects all the peoples of the earth: “The development of peoples – says the encyclical – depends, above all, on a recognition that the human race is a single family, working together in true communion, not simply a group of subjects who happen to live side by side” (n. 53).

Evidently, this new worldwide scale of the human phenomenon would not be possible without technology. First, the latter was linked to printing and transportation. Now, the communications electronic revolution has allowed worldwide circulation of capital and information of all kinds, and has permitted the virtual presence of people and events in real time, at any place on earth. Such a powerful tool, from which humanity has benefited with abundant fruits in all areas of social activity, is modifying, nevertheless, the very mentality of the people, with the resulting danger that they stop looking for the ultimate meaning of everything. The Pope says: “Technological development can give rise to the idea that technology is self-sufficient when too much attention is given to the ‘how’ questions, and not enough to the many ‘why’ questions underlying human activity. For this reason, technology can appear ambivalent. Produced through human creativity as a tool of personal freedom, technology can be understood as a manifestation of absolute freedom, the freedom that seeks to prescind from the limits inherent in things. The process of globalization could replace ideologies with technology, allowing the latter to become an ideological power that threatens to confine us within an a priori that holds us back from encountering being and truth” (n. 70). The phrase reminds me right away of Nietzsche’s statement in which nihilism is that situation that lacks finality and the answer to the why question. Now, it seems not only to lack the answer, but also the very question. Nietzsche appealed to the dissatisfaction of the answers offered by metaphysics in connection with human destiny, thinking that it placed values in a sphere in which human beings could not reach. Now, instead, it seems that technology brings values more accessible to a great number of people. However, such values do not refer to the “why,” but only to the “how,” with the risk of finding answers only to the question for efficiency and utility. Therefore, the Pope states that the substitution of ideologies for technique transforms itself into an ideological power, exceeding its instrumental condition until it becomes a judgment criterion and an offer of a sort of pseudo finality. Unfortunately, it is not about an eventual danger, but of a situation that we can daily verify in politics, economics, social media, and even in the very cultural phenomenon’s, as it testifies to the widespread “new age.” But the field that certainly becomes more burdensome than any other is the biotechnological manipulation of human life itself, depriving it of its received gift character to transform it into a product ordered to the corresponding industry.

Therefore, the encyclical wants to offer a judicious and different judgment criterion, which allows an exit from the confinement of the technological a priori towards the truth of being. For this, it is necessary to restore the question of finality. The text continues: “When the sole criterion of truth is efficiency and utility, development is automatically denied. True development does not consist primarily in ‘doing.’ The key to development is a mind capable of thinking in technological terms and grasping the fully human meaning of human activities, within the context of the holistic meaning of the individual’s being” (n.70). This horizon of meaning is the one proposed from the key textual interpretation which represents the observation of all social events with the eyes of “charity in truth.” Christian anthropology usually summarizes it in the formula “being made for gift,” since all intelligence and human freedom is played in the answer that people want to give to the gift of life received and accepted as a gift. From this horizon, technology is discovered in its humanity. The encyclical says: “Technology –it is worth emphasizing– is a profoundly human reality, linked to the autonomy and freedom of man. In technology we express and confirm the hegemony of the spirit over matter” (n. 69). And appealing to the teachings of John Paul II on human work it continues: “It touches the heart of vocation for human labor: in technology, seen as the product of his genius, man recognizes himself and forges his own humanity. Technology is the objective side of human action whose origin and raison d’être is found in the subjective element: the worker himself. For this reason, technology is never merely technology. It reveals man and his aspirations towards development, it expresses the inner tension that impels him gradually to overcome material limitations. Technology, in this sense, is a response to God’s command to till and to keep the land (cf. Gen 2:15) that he has entrusted to humanity, and it must serve to reinforce the covenant between human beings and the environment, a covenant that should mirror God’s creative love” (n.69).

This priority that puts the magisterium in the subjective dimension of human work on its objective dimension is what leads intelligence to discover development as a vocation and a response to the original exhortation of God’s creative love that puts the human being on his path towards his destiny. As Heidegger explains very well, technology is a way of approximation to reality that considers the latter as magnitude; that is to say, as something capable of being measured and compared in its quantity. But this is a capacity which human intelligence is able to discover, and which cannot be applied to the spiritual life, which exceeds all magnitude when it comprehends selfless love and life itself. From technology itself comes the name of “chance,” a word beyond technology which expresses the confession of perplexity, of not knowing the cause or origin of the considered reality. For the very spirit of intelligence, chance cannot exist, since the very act of comprehension, including the expression “chance,” is preceded or anticipated by the initial exhortation which provokes in intelligence the act of asking and which puts the latter on the road of thought. Therefore, intelligence that seeks truth is open to charity which by its own nature is excessive and overabundant of the gift.

From the action’s point of view, the freedom which arises and comprehends itself from this human tendency toward gift, is not indeterminism or indifference, but the search for the responsibility of one’s own acts, and the rest of humanity with whom we remain related, to lead them to the path which carries out vocation. Therefore, the Pope states that “human freedom is authentic only when it responds to the fascination of technology with decisions that are the fruit of moral responsibility. Hence, the pressing need for formation in an ethically responsible use of technology. Moving beyond the fascination that technology exerts, we must reappropriate the true meaning of freedom, which is not an intoxication with total autonomy, but a response to the call of being, beginning with our own personal being” (n.70). In this sense, one understands the responsibility that human beings have for the realization of common good, which is not a generic general good for all men, but that good which relationally shared allows for the reciprocal realization of vocation. We Christians know that this human vocation which is carried out in goodness, truth, and beauty is called holiness. But even those who have not received the gift of faith will be able to understand that the goods one is expecting can only be a result of the moral responsibility assumed in the communion that comes from a shared culture.

I think that many people could understand the message of this encyclical as an answer to the economic and financial crisis experienced by the world in the last two years. You will find numerous passages of this pontifical text that are enlightening in this respect. But the challenges that the Pope identifies at this time of global emergency in society, a worldwide interdependence as he calls it, is much deeper and of broader scope. While Paul VI and John Paul II had been able to still identify, in their respective epochs, the anthropological errors that were nestled in the ideologies that sought the legitimation of different ways of power; Benedict XVI’s new encyclical identifies technology instead with the pretension of human self-sufficiency or with technology itself turned into an “ideological power.” Thereby, the interlocutor of the pontifical discourse is not only the powers of the state and its governments, but all human beings that use technology to produce and rule the daily rhythm of their work and decision making. The traditional distinction between the public and private sphere is today equally crossed by technology: from economy to health, from sports to formal education, from family to procreation, from mass media to politics. In all these areas and many others, technology embodies this new form of self‑sufficiency which disorients human beings from their purpose, and consequently, from where they can put their hope confidently. The magisterium of this Pope seems to indicate to us that the only thing that can counteract this technology’s unilateral vision of the orientation of the human process and its development is the intelligence that arises from the three theological virtues; since its recognition opens reason to grace, to that which transcends human life, because they do not correspond to the design of a product of human work, but to divine grace which is received with the freedom and responsibility that should correspond to the reception of a gratuitous gift. The invitation, accordingly, is to pass from the “how” questions to the “why” questions, so that they will be a response to the infinite longings of those created in the image and likeness of their Creator, a response which is the only one that can guarantee a social coexistence in justice and peace.

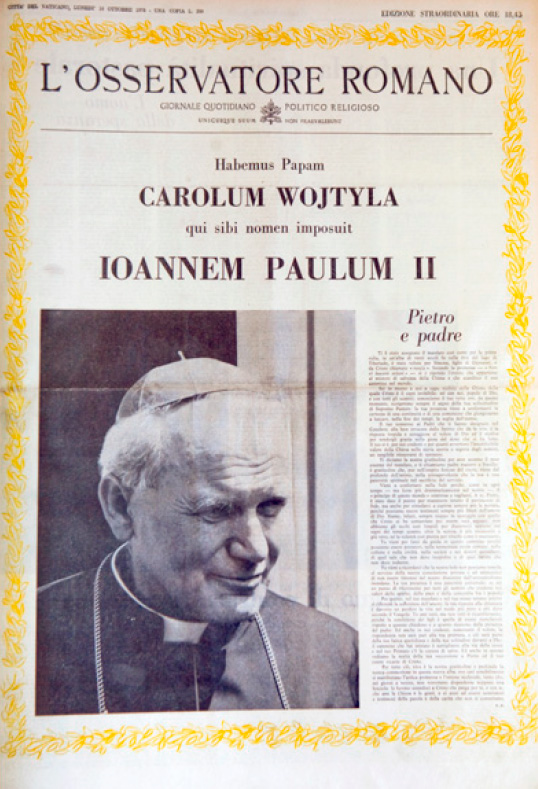

John Paul II began his first encyclical with the words “Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of Man, is the Center and Purpose of Human History”. In doing so he fired a shot across the bows of the then fashionable Marxism, for whom the history of the world was determined by the dynamics of class conflict. As the Saarland philosopher Peter Wust wrote in his 1931 work Crisis in the West, Christian self-knowledge meant the discovery for the first time of the complete extent of man’s metaphysical structure, and of the entire actual and potential range of his history1. The International Theological Commission under the chairmanship of Cardinal Ratzinger expressed the position thus:

In the last time inaugurated at Pentecost, the risen Christ, Alpha and Omega, enters into the history of peoples: from that moment, the sense of history and thus of culture is unsealed and the Holy Spirit reveals it by actualizing and communicating it to all. The Church is the sacrament of this revelation and its communication. It recenters every culture into which Christ is received, placing it in the axis of the world which is coming, and restores the union broken by the Prince of the world. Culture in thus eschatologically situated; it tends towards it completion in Christ, but it cannot be saved except by associating itself with repudiation of evil.

Using the language of Trinitarian appropriations, the English Dominican, Aidan Nichols has addressed the subject of what it mean for a culture to be centered on Christ:

First, a culture should be conscious of transcendence as its true origin and goal, and this we call culture’s tacit “paterological” dimensions, its implicit reference to the Father. Second, the forms which a culture employs should manifest integrity – wholeness and interconnectedness; clarity – transparency to meaning; and harmony – a due proportion in the ways that its constituent elements related to the culture as a whole. And since these qualities – integrity, clarity, and harmony – are appropriated in classical theology to the divine Son, the “Art” of God and splendor of the Father, we can call such qualities of the beautiful form the specifically Christological aspect of culture… and thirdly, then, in the Trinitarian taxis, the spiritually vital and health-giving character of the moral ethos of our culture yield up culture’s pneumatological dimension, its relation to the Holy Spirit.2

In the celebration of the 30th anniversary of Pope John Paul II’s Christological encyclical, I will narrow my analysis to the contemporary problems associated with what Nichols calls the Christological dimension. In particular I would like to address the question of why the Christological dimension is so weak within countries of the western world.

«A starting place for this analysis is Alasdair MacIntyre’s judgment that the institutions of contemporary Western culture are a site of civil war between the proponents of tree rival versions of morality, justice and truth. These are broadly categorized as the classical-theistic synthesis, the eighteenth century Enlightenment philosophies and the 19th century Romantic reactions to the Enlightenment in its Nietzschean form»A starting place for this analysis is Alasdair MacIntyre’s judgment that the institutions of contemporary Western culture are a site of civil war between the proponents of three rival versions of morality, justice, and truth. These are broadly categorized as the classical-theistic synthesis, the eighteenth century Enlightenment philosophies, and the 19th century Romantic reactions to the Enlightenment in its Nietzschean form. MacIntyre believes that each of these three dominant traditions come with their own lists of virtues and vices, their own notions of rationality and justice and their own approach to the relationship between faith and reason. In any given institution it is possible to find proponents of all three traditions, though in some institutions like courts and parliaments, one can find a dominance of Enlightenment types, while in institutions such as universities and the more artistically oriented professions, there is a dominance of the Romantic, Nietzschean types.

«A starting place for this analysis is Alasdair MacIntyre’s judgment that the institutions of contemporary Western culture are a site of civil war between the proponents of tree rival versions of morality, justice and truth. These are broadly categorized as the classical-theistic synthesis, the eighteenth century Enlightenment philosophies and the 19th century Romantic reactions to the Enlightenment in its Nietzschean form»A starting place for this analysis is Alasdair MacIntyre’s judgment that the institutions of contemporary Western culture are a site of civil war between the proponents of three rival versions of morality, justice, and truth. These are broadly categorized as the classical-theistic synthesis, the eighteenth century Enlightenment philosophies, and the 19th century Romantic reactions to the Enlightenment in its Nietzschean form. MacIntyre believes that each of these three dominant traditions come with their own lists of virtues and vices, their own notions of rationality and justice and their own approach to the relationship between faith and reason. In any given institution it is possible to find proponents of all three traditions, though in some institutions like courts and parliaments, one can find a dominance of Enlightenment types, while in institutions such as universities and the more artistically oriented professions, there is a dominance of the Romantic, Nietzschean types.

MacIntyre observes that in cultures characterized by conflicts of values between and within institutions individuals are encouraged to fragment the self and wear different masks in different contexts in order to avoid social marginalization. The Czech intellectual Vaclav Havel has described this behavior as being like people on a football field who are playing for a number of different teams at once, each with a different uniform and not knowing to which team they ultimately belong. MacIntyre argues that the behavior of the Sartrean rebel, a popular sociological species in intellectual and artistic circles of the 1960s, was an attempt by the self to defend its integrity from the bureaucratic practices which divided it into its rôle-governed functions; while the contemporary post-modern celebration of difference is also, at least in part, a reaction against what Weber identified as the iron cage of instrumental reason. Far from being “value neutral” MacIntyre believes that bureaucratic practices are ideological, that is, specifically designed to serve a political end, in this case that of concealing the conflict between the three dominants traditions. Since liberalism operates so as to preclude appeals to what might be described loosely as “ultimate values” there is a social trend toward undermining the prudential judgment of professionals and circumscribing their actions with allegedly value neutral mandatory regulations. As a consequence, John Milbank has noted that professionals are “no longer trusted, but instead must be endlessly spied upon, and measured against a spatial checklist of routinized procedure, that is alien to all genuine inculcation of excellence.”3

Milbank also argues that in contemporary Western society, the sovereignty of Christ has been replaced by the sovereignty of the mob. In his presentation of this thesis he applies Giorgio Agamben’s account of the homo sacer in Roman jurisprudence to an analysis of the trial of Christ. After the succession of the plebs in Rome it was granted to them the right to pursue to the death someone whom they as a collective had condemned. Such an individual was declared homo sacer – a person cast out from the community. For Milbank, Christ was homo sacer some three times over. He is abandoned first by the Jewish leaders to the Roman governor, then by those representing the sovereignty of Rome to the sovereign-executive mob, then finally by the sovereignexecutive mob to the Roman soldiers. Milbank concludes that neither Jewish nor Roman law could be relied upon to condemn Christ, only a mob into which sovereign power and plebiscitory delegation had been collapsed could achieve this 4.

The “sovereignty of the mob” and its juxtaposition with the sovereignty of Christ is a recurring theme in Milbank’s analysis of contemporary Western culture. Following Jean-Yves Lacoste and Olivier Boulnois, Milbank argues that the sovereignty of Christ was lost with the rise of modern philosophy which did not simply emancipate itself from theology but arose from within the space of “pure nature” – something he regards as “a fiction” created by theologians in the Baroque era. Whereas in the pre-modern reading, the Incarnation of Christ and the hypostatic descent of the Holy Spirit inaugurated on earth a counter-polity exercising a counter-sovereignty, nourished by sovereign victimhood, in the theology of the Baroque era, particularly in the work of Suarez (1545- 1617), a dualism developed between nature and grace and the natural and the supernatural, with the natural eventually finding itself equated with the secular and the supernatural finding itself equated with the sacred.

The Suarezian political theory was highly popular in midtwentieth century Catholic social thought, but its claims to a classically Thomist pedigree have been severely questioned, and it is now generally agreed that the notion of there being “two ends” to human nature, one natural, and one supernatural, and corresponding secular and sacred orders, is alien to classical Thomism. As the Thomist scholar, Fr. I. Th. Eschmann noted, “however independent Church and State are, [in the thought of St Thomas] they do not escape being parts of one res publica hominum sub Deo, principe universitatis.”5 Catholic scholars calling themselves “Whig Thomists”, an expression coined by Michael Novak, continue to foster the Suarezian dualism, and this fault line between those who follow Suarez and those who prefer a more pre-modern interpretation is pivotal for theological engagements with the phenomena of modern and post-modern culture. A new generation of Catholic political philosophers and theologians is emerging who prefer the Augustinian concept of the two cities, to the Suarezian concept of the two ends. As Williams T Cavanaugh has expressed the idea:

Augustine does not map the two cities out in space, but rather projects them across time. The reason that Augustine is compelled to speak of two cities is not because there are some human pursuits that are properly terrestrial, and others that pertain to God, but simply because God saves in time. Salvation has a history, where climax is in the advent of Jesus Christ, but whose definitive closure remains in the future. Christ has triumphed over the principalities and powers but there remains resistance to Christ’s saving action. The two cities are not sacred and profane spheres of life. The two cities are the already and the not yet of the Kingdom of God 6.

«The Suarezian political theory was highly popular in mid-twentieth century Catholic social thought, but its claims to a classically Thomist pedigree have been severely questioned, and it is now generally agreed that the notion of there being “two ends” to human nature, one natural, and one supernatural, and corresponding secular and sacred orders, is alien to classical Thomism».According to Cavanaugh’s reading of intellectual and social history, the modern state arose not by secularizing politics but by supplanting the imagination of the body of Christ with an heretical theology of salvation through the state7. While modernity represents salvation through the state, post-modernity is coming to represent salvation through globalization.

«The Suarezian political theory was highly popular in mid-twentieth century Catholic social thought, but its claims to a classically Thomist pedigree have been severely questioned, and it is now generally agreed that the notion of there being “two ends” to human nature, one natural, and one supernatural, and corresponding secular and sacred orders, is alien to classical Thomism».According to Cavanaugh’s reading of intellectual and social history, the modern state arose not by secularizing politics but by supplanting the imagination of the body of Christ with an heretical theology of salvation through the state7. While modernity represents salvation through the state, post-modernity is coming to represent salvation through globalization.

When the sovereignty of Christ is replaced by the sovereignty of the mob, the consumption of the Body and Blood of Christ is replaced by the consumption of brands which serve as symbols of some desired personal or social attribute. According to Naomi Klein, the author of the 2002 best seller No Logo, brand-name multinational corporations sell images and lifestyle rather than simple commodities: “Branding is about ideas, attitudes, lifestyle, and values all embodied in the logo. The ‘transcendental logo’ replaces the corporeal world of commodities, of ‘earthbound products.’” 8 For example, a pair of Dolce & Gabbana underpants will cost several times the money of the same garment without the embroidered D & G logo. The consumer does not buy the expensive designer label product because of superior quality fabric or tailoring, but because he believes that the logo will pseudo-sacramentally convey a desired social attribute such as the physical prowess of David Beckham who was paid millions of British pounds to be photographed wearing the product. The market power of brands and logo attest to a sublimated need in post-modernity for the sacramental that is, for signs and symbols which give definition to the individual self. De Maeseneer, in a fascinating essay comparing the reception of the stigmata by St. Francis of Assisi, with the mechanisms by which brand logos are engraved on the human memory, develops the thesis that brand-name multinational corporation have their own theo-programme9. Places like Eurodisney and the various Disney emporia are not only in the words of one of my French friends, “a cultural Chernobyl” but it is argued that they are a secular culture’s analogue for sacred spaces which hold out the promise of an escape from the mundane.

Williams Cavanaugh believes that “the kenosis of God creates the possibility of a human subject very different from the consumer self. However he reaches the conclusion that the Trinitarian solution to the homeless ego in search of a symbol by which to define itself, is currently eclipsed by the market. The logos of designer brands have replaced the Eucharist as the source of the unity or disunity of the self”10. For Cavanaugh and Milbank, the current global neo-liberalism represents a rival sacrality to that of Christ: “Economic relations do not operate on value-neutral laws, but are rather carriers of specific convictions about the nature of the human person, its origins and its destiny. There is an implicit anthropology and an implicit theology in every economics,”11.

In contrast to the ideology of global neo-liberalism, Cavanaugh believes that a Eucharistic theology “produces a catholicity which does not simply prescind from the local, but contains the universal Catholic within each local embodiment of the Body of Christ”12. As a consequence, “the consumer of the Eucharist is no longer the schizophrenic subject of global capitalism, awash in a sea of unrelated presents, but walks into a story with a past, present, and future.”13. Christianity rather than the ideology of neo-liberalism is the tradition in which the division between plain folk and aristocrat, universal and particular, parish and global community, can ultimately be reconciled. Within this tradition there is a most sacred place, but it exists beyond time in the eternity of the New Jerusalem; while in the period between the first Easter and the consummation of the world, the Eucharist unites the universal and the particular in a multitude of sacred places across the globe. This Eucharist theology and its linking of love and social life is powerfully expressed by Benedict XVI in his Apostolic Exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis:

Man is created for that true and eternal happiness which only God’s love can give. But our wounded freedom would go astray were it not already able to experience something of that future fulfillment. Moreover, to move forward in the right direction, we all need to be guided towards our final goal. That goal is Christ himself, the Lord who conquered sin and death, and who makes himself present to us is a special way in the Eucharistic celebration. Even though we remain “aliens and exiles” in this world (1 Pet 2:11), through faith we already share in the fullness of risen life. The Eucharist banquet, by disclosing its powerful eschatological dimension, comes to the aid of our freedom as we continue our journey 14.

In this Exhortation Pope Benedict goes on to link the sacrament of charity, as he calls the Eucharist, with the love of man and woman united in marriage. The marriage bond is intrinsically linked to the Eucharistic unity of Christ, the Bridegroom, to His Bride, the Church. This vision of the Eucharist as both an affirmation of the freedom of the individual person, and a source of unity, has been poetically expressed by Gottfried Benn, a twentieth century German medical doctor and expressivist poet. In the poem Verlorenes Ich (The Lost Ego), he wrote:

«According to Cavanaugh’s reading of the intellectual and social history, the modern state arose not by secularizing politics but by supplanting the imagination of the body of Christ with an heretical theology of salvation through the state. While modernity represents salvation through the state, post-modernity is coming to represent salvation through globalization.»

«According to Cavanaugh’s reading of the intellectual and social history, the modern state arose not by secularizing politics but by supplanting the imagination of the body of Christ with an heretical theology of salvation through the state. While modernity represents salvation through the state, post-modernity is coming to represent salvation through globalization.»

Oh, when they all bowed towards one center and even the thinkers only thought the god, when they branched out to the shepherds and the lamb, each time the blood from the chalice had made them clean and all flowed from the one wound, all broke the bread that each man ate – oh, distant compelling fulfilled hour, which once enfolded even the lost ego 15.

«Prescriptively, Balthasar notes that “the task of making the historical existence of Christ the norm of every individual existence is the work of the Holy Spirit and that everything in the sacramental order has to be embedded in the personal level, as mediation and encounter, as a gesture expressing personal intention, and hence it always communicates personal, historical graces, and creates personal, historical situations”».

«Prescriptively, Balthasar notes that “the task of making the historical existence of Christ the norm of every individual existence is the work of the Holy Spirit and that everything in the sacramental order has to be embedded in the personal level, as mediation and encounter, as a gesture expressing personal intention, and hence it always communicates personal, historical graces, and creates personal, historical situations”».

If the above represents a pathology report on where the Christological dimension is weak it does not entirely answer the question of why. While one can say that secularism is an alternative religion and that the sovereignty of the mob has replaced the sovereignty of Christ, and that the lost ego is wandering around the marketplaces of the world in search of a spiritual home, fascinated by the signs and symbols of companies by which a self-identity might be constructed, these explanations still do not explain why the Church has been so pastorally ineffective for such social conditions to exist.

Here it may be argued that the problem is fundamentally liturgical. In his account of the rise of secularism, von Balthasar begins with the period of the Renaissance in which there is a transformation from cultural achievement being a result of a life steeped in the liturgical consecration of religion, to a situation where cultural achievement as an end in itself takes priority. He suggest that this transition in the Renaissance mirrors a similar transition in the classical era from Aeschylus, for whom art was still a part of liturgical life, to Euripides for whom it had already become an end in itself. Prescriptively, Balthasar notes that the “task of making the historical existence of Christ the norm of every individual existence is the work of the Holy Spirit and that everything in the sacramental order has to be embedded in the personal level, as mediation and encounter, as a gesture expressing personal intention, and hence it always communicates personal, historical graces, and creates personal, historical situations.” 16.

The question is thus one of addressing how the sacramental is embedded in the personal. Here the work of Jean Borella is helpful. Borella argues that the sense of the supernatural is a sense of a higher nature or a sense that the possibilities of existence do not limit themselves to what we ordinary experience. In order for this sense to be awakened in people, they need to have an experience of forms which by themselves refer to nothing of the mundane. While elements of the physical world are always involved –otherwise no experiences of it would be possible– they are set aside from the natural order to which they originally belonged and consecrated in order to render present realities of another order.17 As Louis Duprè emphasizes, the purpose of a ritual act is not to repeat the ordinary action which it symbolizes, but to bestow meaning upon it in a higher perspective. A reduction of ritual gestures to common activity would defeat the entire purpose of ritualization, which is to transform life, not to imitate it. 18

«Until these problems are resolved the Christological dimensions of Western culture will continue to be weak because the sacramental order will not be sufficiently embedded in the personal. Not only will our youth not love the Eucharist but their intellects will not be very receptive to the work of the Holy Spirit because their memories will not include within them something like a Transfiguration moment».

«Until these problems are resolved the Christological dimensions of Western culture will continue to be weak because the sacramental order will not be sufficiently embedded in the personal. Not only will our youth not love the Eucharist but their intellects will not be very receptive to the work of the Holy Spirit because their memories will not include within them something like a Transfiguration moment».

While it is difficult to generalize across the entire Western world, certainly in the English speaking parts of it, the liturgical practices have been quite problematic since at least the 1970s. What Pope Benedict calls pastoral pragmatism or bringing God down to the level of the people, parish tea party liturgy and sacro-pop music has been a dominant part of any Catholic child’s experience of liturgy over the past 40 years.

Until these problems are resolved the Christological dimensions of Western culture will continue to be weak because the sacramental order will not be sufficiently embedded in the personal. Not only will our youth not love the Eucharist but their intellects will not be very receptive to the work of the Holy Spirit because their memories will not include within them something like a Transfiguration moment. Their liturgical and sacramental experience will not have sufficiently liberated them from the mundane. Their choices will appear to be between following the mob and searching for a self-identity among the signs and symbols of the market, or pursuing the option of the Sartrean or Nietzschean rebel, which, while representing a kind of liberation from the mob, requires a foundational stance against love, that is, against the kind of human commitments that appear to place limit on the exercise of human freedom.

«When the sovereignty of Christ is replaced by the sovereignty of the mob, the consumption of the Body and Blood of Christ is replaced by the consumption of brands which serve as symbols of some desired personal or social attribute».

«When the sovereignty of Christ is replaced by the sovereignty of the mob, the consumption of the Body and Blood of Christ is replaced by the consumption of brands which serve as symbols of some desired personal or social attribute».

The first option, following the mob, represents a variety of inauthenticity which the young Karol Wojtyla called servile conformism, while the second option represents a kind of inauthenticity described by Wojtyla as non-involvement – a Stoic withdrawal from community and public life on the grounds that it is all too banal or requires too much self-giving. The notion that one only finds oneself though acts of love (the Gaudium et Spes 24 theme) is precisely what the Nietzschean rejects. For the Nietzschean, Gaudium et Spes 24 is the moral outlook of the slave. The servile conformism to the object of desire of the mob is not a deliberate rejection of true love, it is just a case of not knowing where real love can be found. However the option of noninvolvement, of a Stoic withdrawal into the personal dreams or projects of the emotionally unattached self, does represents a conscious foreclosure against love.

Thus, the solutions of the problems of the weakness of the Christological dimension seem to lie in the fields of sacramentality, especially the sacrament of the Eucharist, and in liturgy, which again is intimately related to the Eucharist. They also lie in taking a critical stance towards the trend to undermine the prudential judgment of professionals by circumscribing the exercises of their judgment with bureaucratic regulation, designed to prevent them from promoting their moral values. In the West, no less than in the formerly Communist countries, people need to learn to live in truth and resist having their integrity undermined by ideological regulations. Moreover the Church herself needs to resist being entangled by such regulations and the tendency to mimic modern corporate practices.

The beatified John Henry Newman wrote that the Church is not a mere creed or philosophy but a counter kingdom before which all must bow down and lick the dust of her feet so that the world may become a fit object of love.19 The sovereignty of Christ is exercised through His Church and his personal contact with his subject is effected through her ministry of the sacraments, themselves embedded within liturgical rites. One can thus take the theological anthropology of Redemptor hominis and the liturgical theology of Sacramentum Caritatis and see the second as providing the cultural healing that needs to be undertaken for the first to be restored as the infrastructural principle of western civilization, and indeed the whole world. As the English philosopher Roger Scruton has concluded:

The high culture of Europe acquired the universality of the Church which had engendered it. At the same time the core experience of membership survived, to be constantly represented in the Mass – the “communion” which is also an enactment of community. It is in this experience that our common culture renewed itself, and the arts of our culture bears witness to it, either by honoring or by defiling the thought of God’s incarnation. 20

The second of June 1980, John Paul II went to UNESCO in Paris, to deliver one of the most important and memorable speeches on human culture. Shortly afterwards he created the Pontifical Council for Culture dedicated to the pastoral care and the promotion of dialogue between the Church and all cultures.

The pastoral concern of the Church for culture today comes from Vatican II and it is contained in one whole chapter: Pastoral Constitution, Gaudium et spes. Well known is the theme it proposed to resume the Christian itinerary in the field of culture and taken up by the former Pontifical Magisterium: “strive to make human life more human.” This means that human life is not only a gift, individually assumed and accepted, but a vocation of communion amongst peoples and cities, and as Paul VI taught in Populorum progressio and Benedict XVI followed up in Caritas in veritate, the authentic development and progress of humanity not only implies material welfare, but most important, the spiritual development in solidarity and charity.

The Council certainly had in mind, as context, the destruction of Europe produced by the Second World War, the reshuffling of international geopolitics and the alignment of the Cold War, the hopeful creation of a worldwide judicial order through the organization of the United Nations and the process of decolonialization produced later in various regions of the planet; all of which made indispensable the start of a new dialogue, one that took into account the inviolable dignity of human beings, and that respected and furthered the legitimate effort of many countries to recover the originality of its history and traditions, where they had been forgotten or submitted to the ideological imperatives of the dominating powers.

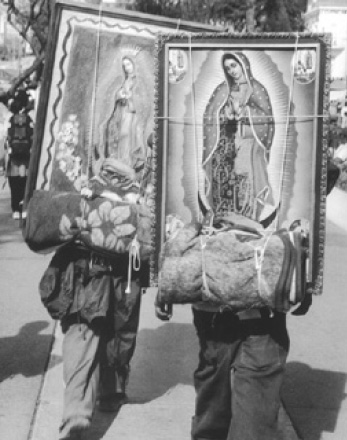

To make human life more human was an itinerary of reconstruction and reconciliation in a worldwide scale, which the Church wanted to serve with special solicitude. The Church’s faith in the Incarnation of the Son of God, who assumed the human condition, made the Church strongly proclaim that “the mystery of man only became clear in the light of the mystery of the Verb Incarnate” as stated in Gaudium et spes (n22) that John Paul II never tired to repeat. And in that same paragraph of the Constitution it is suggested that the Holy Spirit, though mysteriously, also promotes sanctity amongst unbelievers. “Since Christ died for every man and the ultimate vocation of man is effectively only one: divine vocation, we must sustain that the Holy Spirit offers every one the possibility, in a way only known to God, to associate with the paschal mystery.”

Thus we may consider, using the Patristic expression, that there exist “seeds of the Verb” in all cultures, which show the human being as the image and likeness of his Creator. So, the consideration of culture has at its centre man himself, his dignity, his vocation and mystery. John Paul II recalls this on the first part of his message to the UNESCO, he states: “The fundamental dimension [human cohabitation] is man, man as a whole, man living at the same time within the sphere of material and spiritual values. The respect for the inalienable rights of the human person is the basis of everything.” (Quoting his own speech at the UN on October, 1979) (n 4). The need for this respect stems from the human being himself, “from the dignity of his intelligence, of his will and of his heart” (ibid). This dignity is the premise of every culture.

For this reason, it is interesting to point out that Pope Wojtyla never considered in his anthropological thought, that human dignity should be justified or deduced from other arguments apart form man’s own existence, conscious of it by his intelligence, his will and his heart. He evidently thought that the human being could alienate himself, that sin could bewilder the rightful conscience of himself, and that in the tragic twentieth century this had actually happened. To found or recognize again his injured dignity, the human being only had to be faithful to the itinerary of his own conversion. This is beautifully reflected in the most moving moment of his speech at the UN, when recalling Pilate’s words, he proclaims plainly: Ecce homo. Without intending it, Pilate had pronounced at that moment, the most profound truth about man.

«One can be a great producer without being a cultivator. In this sense a person can be civilized without culture, even against culture. I can see how ‘producture’, this technical civilization based on possessions, has reduced itself, has locked itself in its own immanence, and automatically becomes anti culture, because it is contrary to love, liberty, dignity, justice and peace.» (In the picture, Stanislaw Grygiel)The following paragraphs are devoted to explain this truth in its intimate and indestructible relationship with culture. He relies on the assertion of Saint Thomas Aquinas: Genus humanum arte et ratione vivit (n.6). “The essential meaning of culture consists, according to the words of St. Thomas Aquinas, in the fact that it is a characteristic of human life as such. Man lives a really human life thanks to culture… Culture is specific way of man’s ‘existing’ and ‘being’. Man always lives according to a culture which is specifically his, and which, in its turn, creates among men a tie which is also specifically theirs, determining the interhuman and social character of human existence” (ibid). In the same way as no one chooses from whom to be born nor what family to belong to, neither does he choose the culture which becomes to him the gift that receives him, the set of personal and social relationships that will help him to conform to the community that makes possible such relationships. Zubiri, the philosopher, teaches that the dynamics of the person is not his formation, but his conformation, since before the person can have conscience of his originality and of the unique responsibility which it implies, others have come first to welcome him and offer him their world as something worthy of inhabiting. In fact, many thinkers also talk about culture as a “second nature,” since it determines for men, as the Pope says, the specific way of existing and being. This manner of insertion of the human being into reality, invites him to understand that within culture “being” comes before “having,” priority which has been altered so many times in the society of comfort, consumerism and opulence. Says the Pope, “Man who, in the visible world, is the only ontic subject of culture is also its only object and its term. Culture is that through which man as man, becomes more man, ‘is’ more, has more access to ‘being’… The experience of the various eras, without excluding the present one, proves that people think of culture and speak about it in the first place in relation to man then only in a secondary and indirect way in relation to the world of his products” (n.7). This statement reminds of an interview given by the Polish philosopher and disciple of Karol Wojtyla, Stanislaw Grygiel, which appeared in Humanitas No. 31, Winter 2003, in which interpreting the idea of the Pope opposed culture and “producture.” He remarked, “Culture resides in desiring, in acting, in meaning, in loving and knowing, in practicing justice, peace and acting in a peaceful way. This is culture. If we reduce our life only to the making of eyeglasses, books, shoes, to producing things, we do not live within culture but in “producture.” One can be a great producer without being a cultivator. In this sense a person can be civilized without culture, even against culture. I can see how “producture,” this technical civilization based on possessions, has reduced itself, has locked itself in its own immanence, and automatically becomes anti culture, because it is contrary to love, liberty, dignity, justice and peace.”