The second of June 1980, John Paul II went to UNESCO in Paris, to deliver one of the most important and memorable speeches on human culture. Shortly afterwards he created the Pontifical Council for Culture dedicated to the pastoral care and the promotion of dialogue between the Church and all cultures.

The pastoral concern of the Church for culture today comes from Vatican II and it is contained in one whole chapter: Pastoral Constitution, Gaudium et spes. Well known is the theme it proposed to resume the Christian itinerary in the field of culture and taken up by the former Pontifical Magisterium: “strive to make human life more human.” This means that human life is not only a gift, individually assumed and accepted, but a vocation of communion amongst peoples and cities, and as Paul VI taught in Populorum progressio and Benedict XVI followed up in Caritas in veritate, the authentic development and progress of humanity not only implies material welfare, but most important, the spiritual development in solidarity and charity.

The Council certainly had in mind, as context, the destruction of Europe produced by the Second World War, the reshuffling of international geopolitics and the alignment of the Cold War, the hopeful creation of a worldwide judicial order through the organization of the United Nations and the process of decolonialization produced later in various regions of the planet; all of which made indispensable the start of a new dialogue, one that took into account the inviolable dignity of human beings, and that respected and furthered the legitimate effort of many countries to recover the originality of its history and traditions, where they had been forgotten or submitted to the ideological imperatives of the dominating powers.

To make human life more human was an itinerary of reconstruction and reconciliation in a worldwide scale, which the Church wanted to serve with special solicitude. The Church’s faith in the Incarnation of the Son of God, who assumed the human condition, made the Church strongly proclaim that “the mystery of man only became clear in the light of the mystery of the Verb Incarnate” as stated in Gaudium et spes (n22) that John Paul II never tired to repeat. And in that same paragraph of the Constitution it is suggested that the Holy Spirit, though mysteriously, also promotes sanctity amongst unbelievers. “Since Christ died for every man and the ultimate vocation of man is effectively only one: divine vocation, we must sustain that the Holy Spirit offers every one the possibility, in a way only known to God, to associate with the paschal mystery.”

Thus we may consider, using the Patristic expression, that there exist “seeds of the Verb” in all cultures, which show the human being as the image and likeness of his Creator. So, the consideration of culture has at its centre man himself, his dignity, his vocation and mystery. John Paul II recalls this on the first part of his message to the UNESCO, he states: “The fundamental dimension [human cohabitation] is man, man as a whole, man living at the same time within the sphere of material and spiritual values. The respect for the inalienable rights of the human person is the basis of everything.” (Quoting his own speech at the UN on October, 1979) (n 4). The need for this respect stems from the human being himself, “from the dignity of his intelligence, of his will and of his heart” (ibid). This dignity is the premise of every culture.

For this reason, it is interesting to point out that Pope Wojtyla never considered in his anthropological thought, that human dignity should be justified or deduced from other arguments apart form man’s own existence, conscious of it by his intelligence, his will and his heart. He evidently thought that the human being could alienate himself, that sin could bewilder the rightful conscience of himself, and that in the tragic twentieth century this had actually happened. To found or recognize again his injured dignity, the human being only had to be faithful to the itinerary of his own conversion. This is beautifully reflected in the most moving moment of his speech at the UN, when recalling Pilate’s words, he proclaims plainly: Ecce homo. Without intending it, Pilate had pronounced at that moment, the most profound truth about man.

«One can be a great producer without being a cultivator. In this sense a person can be civilized without culture, even against culture. I can see how ‘producture’, this technical civilization based on possessions, has reduced itself, has locked itself in its own immanence, and automatically becomes anti culture, because it is contrary to love, liberty, dignity, justice and peace.» (In the picture, Stanislaw Grygiel)The following paragraphs are devoted to explain this truth in its intimate and indestructible relationship with culture. He relies on the assertion of Saint Thomas Aquinas: Genus humanum arte et ratione vivit (n.6). “The essential meaning of culture consists, according to the words of St. Thomas Aquinas, in the fact that it is a characteristic of human life as such. Man lives a really human life thanks to culture… Culture is specific way of man’s ‘existing’ and ‘being’. Man always lives according to a culture which is specifically his, and which, in its turn, creates among men a tie which is also specifically theirs, determining the interhuman and social character of human existence” (ibid). In the same way as no one chooses from whom to be born nor what family to belong to, neither does he choose the culture which becomes to him the gift that receives him, the set of personal and social relationships that will help him to conform to the community that makes possible such relationships. Zubiri, the philosopher, teaches that the dynamics of the person is not his formation, but his conformation, since before the person can have conscience of his originality and of the unique responsibility which it implies, others have come first to welcome him and offer him their world as something worthy of inhabiting. In fact, many thinkers also talk about culture as a “second nature,” since it determines for men, as the Pope says, the specific way of existing and being. This manner of insertion of the human being into reality, invites him to understand that within culture “being” comes before “having,” priority which has been altered so many times in the society of comfort, consumerism and opulence. Says the Pope, “Man who, in the visible world, is the only ontic subject of culture is also its only object and its term. Culture is that through which man as man, becomes more man, ‘is’ more, has more access to ‘being’… The experience of the various eras, without excluding the present one, proves that people think of culture and speak about it in the first place in relation to man then only in a secondary and indirect way in relation to the world of his products” (n.7). This statement reminds of an interview given by the Polish philosopher and disciple of Karol Wojtyla, Stanislaw Grygiel, which appeared in Humanitas No. 31, Winter 2003, in which interpreting the idea of the Pope opposed culture and “producture.” He remarked, “Culture resides in desiring, in acting, in meaning, in loving and knowing, in practicing justice, peace and acting in a peaceful way. This is culture. If we reduce our life only to the making of eyeglasses, books, shoes, to producing things, we do not live within culture but in “producture.” One can be a great producer without being a cultivator. In this sense a person can be civilized without culture, even against culture. I can see how “producture,” this technical civilization based on possessions, has reduced itself, has locked itself in its own immanence, and automatically becomes anti culture, because it is contrary to love, liberty, dignity, justice and peace.”

«One can be a great producer without being a cultivator. In this sense a person can be civilized without culture, even against culture. I can see how ‘producture’, this technical civilization based on possessions, has reduced itself, has locked itself in its own immanence, and automatically becomes anti culture, because it is contrary to love, liberty, dignity, justice and peace.» (In the picture, Stanislaw Grygiel)The following paragraphs are devoted to explain this truth in its intimate and indestructible relationship with culture. He relies on the assertion of Saint Thomas Aquinas: Genus humanum arte et ratione vivit (n.6). “The essential meaning of culture consists, according to the words of St. Thomas Aquinas, in the fact that it is a characteristic of human life as such. Man lives a really human life thanks to culture… Culture is specific way of man’s ‘existing’ and ‘being’. Man always lives according to a culture which is specifically his, and which, in its turn, creates among men a tie which is also specifically theirs, determining the interhuman and social character of human existence” (ibid). In the same way as no one chooses from whom to be born nor what family to belong to, neither does he choose the culture which becomes to him the gift that receives him, the set of personal and social relationships that will help him to conform to the community that makes possible such relationships. Zubiri, the philosopher, teaches that the dynamics of the person is not his formation, but his conformation, since before the person can have conscience of his originality and of the unique responsibility which it implies, others have come first to welcome him and offer him their world as something worthy of inhabiting. In fact, many thinkers also talk about culture as a “second nature,” since it determines for men, as the Pope says, the specific way of existing and being. This manner of insertion of the human being into reality, invites him to understand that within culture “being” comes before “having,” priority which has been altered so many times in the society of comfort, consumerism and opulence. Says the Pope, “Man who, in the visible world, is the only ontic subject of culture is also its only object and its term. Culture is that through which man as man, becomes more man, ‘is’ more, has more access to ‘being’… The experience of the various eras, without excluding the present one, proves that people think of culture and speak about it in the first place in relation to man then only in a secondary and indirect way in relation to the world of his products” (n.7). This statement reminds of an interview given by the Polish philosopher and disciple of Karol Wojtyla, Stanislaw Grygiel, which appeared in Humanitas No. 31, Winter 2003, in which interpreting the idea of the Pope opposed culture and “producture.” He remarked, “Culture resides in desiring, in acting, in meaning, in loving and knowing, in practicing justice, peace and acting in a peaceful way. This is culture. If we reduce our life only to the making of eyeglasses, books, shoes, to producing things, we do not live within culture but in “producture.” One can be a great producer without being a cultivator. In this sense a person can be civilized without culture, even against culture. I can see how “producture,” this technical civilization based on possessions, has reduced itself, has locked itself in its own immanence, and automatically becomes anti culture, because it is contrary to love, liberty, dignity, justice and peace.”

This distorted vision of culture by technical civilization ends up damaging the image that human beings have of themselves, giving priority to the values of efficiency and productivity above those of dignity, love, and liberty. Consequently the Pope adds: “This man who expresses himself and objectifies himself in and through culture, is unique, complete, and indivisible. […] Consequently, he cannot be envisaged solely as the resultant —to give only one example— of the production relations that prevail at a given period. […] A culture without human subjectivity and without human causality is inconceivable: in the cultural field, man is always the first fact: man is the prime and fundamental fact of culture […] in his totality: in his spiritual and material subjectivity as a complete whole” (n.8). In other documents of his Magisterium it is precisely in this human subjectivity and human causality that he bases the sovereignty and the freedom of men and their cultures. Consequently at the same time, human beings are called to assume their responsibilities towards themselves and towards others for their acts of sovereignty and for their consequences within the conscience that each person has of his own dignity. In Wojtyla’s anthropology, man was always considered according to his acts, thought being one of them; but which does not exhaust his subjectivity or the explanation for his causality. Love, on the other hand, summarizes the whole of the dignity of conscience that man acquires from his free actions, hence he can think of culture, in the aforesaid quotation, as “a truly human system, a splendid synthesis of spirit and body.”

«In the same way as no one chooses from whom to be born nor what family to belong to, neither does he choose the culture which becomes to him the gift that receives him, the set of personal and social relationships that will help him to conform to the community that makes possible such relationships. Zubiri, the philosopher, teaches that the dynamics of the person is not his formation, but his conformation, since before the person can have conscience of his originality and of the unique responsibility which it implies, others have come first to welcome him and offer him their world as something worthy of inhabiting.» (In the picture, Xavier Zubiri)

«In the same way as no one chooses from whom to be born nor what family to belong to, neither does he choose the culture which becomes to him the gift that receives him, the set of personal and social relationships that will help him to conform to the community that makes possible such relationships. Zubiri, the philosopher, teaches that the dynamics of the person is not his formation, but his conformation, since before the person can have conscience of his originality and of the unique responsibility which it implies, others have come first to welcome him and offer him their world as something worthy of inhabiting.» (In the picture, Xavier Zubiri)

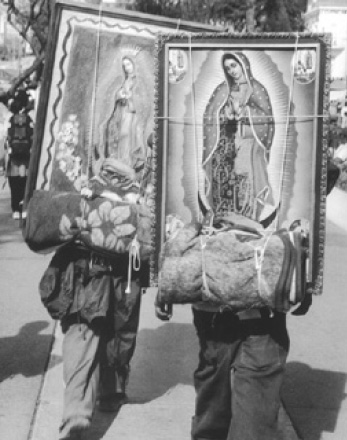

The Pontiff resumes his speech: “the organic and constitutive link which exists between religion in general and Christianity in particular, on the one hand, and culture, on the other hand” (n.9), which manifests itself in diverse specific expressions as in education and art, for example, without forgetting the popular religiosity of common people, make of it an essential component of their cultural identity. He mentions Europe as an example from the Atlantic to the Urals, whose history would be impossible to understand without the substratum of their religious experience. He proclaims his “admiration before the creative riches of the human spirit, before its incessant efforts to know and strengthen the identity of man, this man who is always present in all the particular forms of culture” (ibid). And concludes the explanation of the anthropological basis of culture with one of the most outstanding paragraphs of his teachings about the meaning of the Incarnation and its consequences on human dignity. Says the Pope: “ the fundamental link between the Gospel, that is, the message of Christ and the Church, and man in his very humanity. This link is in fact a creator of culture in its very foundation. To create culture, it is necessary to consider, to its last consequences and entirely, man as a particular and autonomous value, as the subject bearing the transcendency of the person. Man must be affirmed for himself, and not for any other motive or reason: solely for himself! What is more, man must be loved because he is man. Love must be claimed for man by reason of the particular dignity he possesses. The whole of the affirmations concerning man belongs to the very substance of Christ’s message and of the mission of the Church” (n.10).

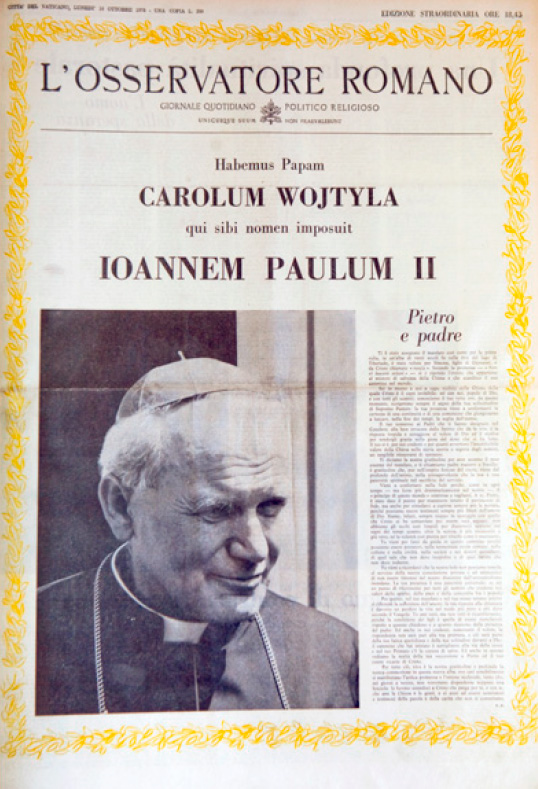

Front page of “L’Osservatore Romano” announcing the election of Karol Wojtyla for the Papacy in October 1978 with the name John Paul II

Front page of “L’Osservatore Romano” announcing the election of Karol Wojtyla for the Papacy in October 1978 with the name John Paul II

This statement on the human being as “the subject bearing the transcendence of the person” seems to me of incomparable precision and beauty. It reminds us that the concept of person was applied first and foremost to Christ and the Holy Trinity, then to the human being; however, the human being has been converted by the Incarnation of the Verb in an icon of the Trinity. To talk about person is to talk about God himself, of the mystery of the communion that unites the Trinity in one and the same nature and dignity; to apply to human beings a qualification of person is, then, to talk of his participation in the Christological vocation of becoming “sons in the Son,” as defined in Gaudium et spes, adding that when He prayed to the Father, “that all may be one… as we are one” (John 17:21-22) opened up vistas closed to human reason, for He implied a certain likeness between the union of the divine Persons, and the unity of God’s sons in truth and charity “ (n.24). This same teaching that John Paul II applied to the relationship of the human being with his culture, he also applied to the nuptial mystery, bestowing an impressive strength of renewal to the theological anthropology as referred to the person, marriage and the family.

On the second part of his speech before UNESCO, the Pope shows the consequences of these essential anthropological statements, which I enumerate briefly in the same order that they appear:

a) Education. The first and essential task of all culture is education. “Education consists in fact in enabling man to become more man… For this purpose man must be able to ‘be more’ not only ‘with others’, but also ‘for others’… he most important thing is always man, man and his moral authority which comes from the truth of his principles and from the conformity of his actions with these principles” (n.11).

b) Family. “There is no doubt that the first and fundamental cultural fact is the spiritually mature man, that is, a duly educated man, a man capable of educating himself and educating others… what can be done in order that man’s education may be carried out above all in the family?” (n.12). Parents basically have the necessary moral authority to educate.

c) Alienation and manipulation of man. “In the process of education as a whole, and of scholastic education in particular, has there not been a unilateral shift towards instruction in the narrow sense of the word? … a real alienation of education instead of working in favour of what man must ‘be’, it works solely in favour of what man can grow in the field of ‘having’, of ‘possession’. The further stage of this alienation is to accustom man, by depriving him of his own subjectivity, to being the object of multiple manipulations: ideological or political manipulations which are carried out through public opinion; those that are operated through monopoly or control, through economic forces or political powers, and the media of social communication; finally, the manipulation which consists of teaching life as a specific manipulation of oneself” (n.13). Most important is to teach to manipulate oneself. These dangers menace specially the technically developed societies. There is a growing lack of confidence in the meaning of the fact of being a man. Instead false “imperatives” are established like the priority of behaving according to what is in fashion, to what is subjective and of quick success.

d) The nation. “… it is, in fact, the great community of men who are united by various ties, but above all, precisely by culture. The Nation exists ‘through’ culture and ‘for’ culture, and it is therefore the great educator of men in order that they may ‘be more’ in the community” (n.14). Referring to the example of Poland, which survived thanks to its culture, he adds: “What I say here concerning the right of the Nation to the foundation of its culture and its future is not, therefore, the echo of any ‘nationalism’, but it is always a question of a stable element of human experience […] There exists a fundamental sovereignty of society which is manifested in the culture of the Nation. It is a question of the sovereignty through which, at the same time, man is supremely sovereign” (ibid). This is a condition to overcome the remains of colonialism.

e) The media. They must be the expression of the sovereignty of the nation and not an instrument of dominion of the agents of political and financial powers. They should strive to be useful in building a more human life.

f) The education of the people and the suppression of analphabetism. The popularization of education is necessary to dispose of and administer the means they have, for their own and the public welfare. It also avoids bloodshed for power.

g) The right of Catholics to a Catholic education. The Church through the centuries has founded schools and universities. The Church supports “the right which belongs to all families to educate their children in schools which correspond to their own view of the world, and in particular the strict right of Christian parents not to see their children subjected, in schools, to programs inspired by atheism. That is, indeed, one of the fundamental rights of man and of the family” (n. 18).

h) The cultivation of science. Man’s vocation to knowledge, as well as the constitutive link of humanity with truth, that become a daily reality in the institutions of education, especially in universities (n.19). After paying homage to scientists the Pope adds: “we must be equally concerned by everything that is in contradiction with these principles of disinterestedness and objectivity, everything that would make science an instrument to teach aims that have nothing to do with it” (n. 20). “The future of man and of the world is threatened, radically threatened … because the marvellous results of their researches and their discoveries, especially in the field of the sciences of nature, have been and continue to be exploited—to the detriment of the ethical imperative—for purposes that have nothing to do with the requirements of science … Whereas science is called to be in the service of man’s life, it is too often a fact that it is subjected to purposes that destroy the real dignity of man and of human life” (n. 21). The speech gives as examples: genetic manipulation, biological experiments, chemical and bacteriological and nuclear warfare. “The cause of man will be served if science forms an alliance with conscience” (n. 22).

«The Pontiff resumes his speech: “the organic and constitutive link which exists between religion in general and Christianity in particular, on the one hand, and culture, on the other hand” (n.9), which manifests itself in diverse specific expressions as in education and art, for example, without forgetting the popular religiosity of common people, make of it an essential component of their cultural identity.»

«The Pontiff resumes his speech: “the organic and constitutive link which exists between religion in general and Christianity in particular, on the one hand, and culture, on the other hand” (n.9), which manifests itself in diverse specific expressions as in education and art, for example, without forgetting the popular religiosity of common people, make of it an essential component of their cultural identity.»

In conclusion the Pope gives three statements that summarize the arguments exposed and that at the same time express a vision and a task for the future: “The future of man depends on culture. Yes! The peace of the world depends on the primacy of the Spirit! Yes! The peaceful future of mankind depends on love!” (n. 23). Many of the elements present in his speech were developed more extensively in other documents of the fruitful Magisterium of John Paul II. Their relevance in this document is related to the fact that it is an early document of his Pontificate that was to announce a future course. Personally, however, I am moved by his passion about man in his specific circumstances: historical and social. “Man has to be asserted because of himself and because of no other reason or motif: just because of being himself” and because of it we have to love all the relations that constitute his being: culture, the family, school, nation and work. In contrast with the instrumental vision that prevails today over all these realities, the Paris speech reminds us that all these realities participate of the being of man and the possibility to carry out his vocation of person.