Man’s ultimate battlefield is the Cross. In it, John Paul II looks for the reunion of the human person and society.

It is enlightening to return to John Paul II’s anthropology after his canonization, together with his predecessor’s, John XXIII. Pope Wojtyla’s view of man, in the pursuit of an answer, is always associated to the mystery of the Incarnate Word. He does so by means of a sui generis “reduction” of man to the Son of God: in Him, there is the realization and defense of the human person. Christ was sent to man as God’s great question, calling the human person towards the dialogue that transfigures him. And the true consideration of man is only reached by the one who incessantly turns to Christ as his Beginning and End. John Paul II does not accept battles for the human person in a field of chaos. He always moves the battlefield to a higher ground, where man’s reality, disintegrated into senseless fragments, is rebuilt in a beautiful landscape. Man’s ultimate battlefield is the Cross. In it, John Paul II looks for the reunion of the human person and society. In front of this “magna quaestio” of God and man “the thoughts of many hearts will be revealed” (Lk. 2:35), and therefore his freedom and order, but also his desire and chaos.

Before becoming John Paul II, Karol Wojtyla saw in man a big question about transcendence. Transcendence—the center towards which human thought and action move—integrates the being in the being-someone. Because of transcendence man is himself.

Transcendence expresses itself through moral experience, in which man moves away from the norms depicted on the cave’s wall and directs all his being towards infinitely distant things… Karol Wojtyla started thinking about the human person precisely from the point of view of the experience of this call to conversion.

Transcendence is not part of the question’s landscape, but the landscape demands transcendence. Without transcendence there would be no landscape, but only a random collection of things that are too close to man’s hands to be able to be what constitute the sense of his being. If transcendence were identified with any of these things, it would also require integration. With transcendence there can only be questioning.

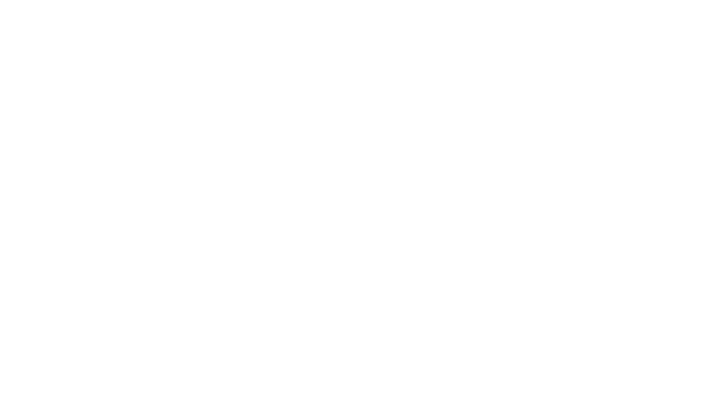

Episcopal Consecration of his personal secretary, now Cardinal Archbishop of Krakow, Stanislaw Dziwisz.

Episcopal Consecration of his personal secretary, now Cardinal Archbishop of Krakow, Stanislaw Dziwisz.

Transcendence announces to man that he is also beyond… As it calls him to what is beyond, it calls him to

itself and to himself. Therefore, through this dialogue, man turns… into someone else. Put in a different way, wisdom’s friend converts himself daily. In the metanoia of his being we find what cardinal Wojtyla called the person’s integration through transcendence.

Through the experience of the moral imperative—and not in this or that system of thought—the truth of the human person is revealed. It is freedom; not any kind of freedom or whim, but freedom that is love and an answer to love. In the experience of freedom compelled to an act of love, man discovers he is a word spoken by someone else before he can utter anything. The human person can be a word that is full of meaning because the word of love is in it, giving it all before receiving.

The word that is man, to whom love has made its announcement, becomes a question about his transcendence. This transformation happens at the moment man understands his inability to locate himself with his own efforts in a landscape that is permanently endowed with meaning, indestructible by suffering and death. The question on transcendence frees man from the landscape’s immanence. Transcendence does not give man any behavioral rules; it just gives itself. Fascinated with the afterlife of transcendence, man knows where to go and feels guilty if he does not grow in that direction. Therefore, the more he converts, the more he feels a sinner. And it must be thus, because the afterlife would not be transcendence otherwise.

Transcendence is present in man’s freedom as “per procura”: a light shines from it that makes the truth of things rise from the chaos of darkness. Everything gains importance with this light, despite its provisional character, so that man cannot but love these things and, at the same time, he can love them in accordance to justice. The truth of things protects his freedom from the degeneration of whim. Love that is inspired by justice makes man’s being fair; it justifies him. Sometimes it must justify him with death.

If he works on the Earth, in all freedom, that is, in the presence of transcendence, man cultivates his being as he cultivates the world’s being. He cultivates it as the peasant cultivates his own field. He cultivates it through the seed thrown on the earth with the hope of a harvest. This work during the wait for fruitfulness is what Karol Wojtyla—and then John Paul II—calls culture. Man’s lack of culture or society shows how both are dominated by whim, which never creates culture and, in fact, does not go beyond comfort and pleasure.

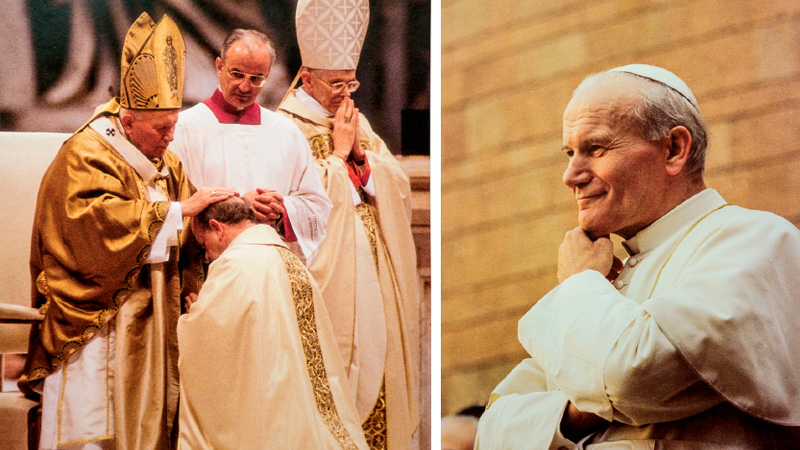

Cardinal Wojtyla salutes his predecessor, Paul VI.

Cardinal Wojtyla salutes his predecessor, Paul VI.

We never see directly a person’s being, i.e. the dialogue of their freedom answering to the Love of transcendence. The person hides his own intimacy to the point of having to guess at it. Everything that is revealed through gesture, which we can only explain with the person’s being that answers to the afterlife of transcendence, leads us towards intimacy in the same way footprints lead hunters in the thicket of the forest to the animal’s lair. The story of the dialogue among men that is deciphered in these gestures allows us only to guess at the story of the dialogue between the human person’s intimacy and He that is “intimior intimo eius,” without whom intimacy would not be so.

To Karol Wojtyla, human actions represent a symbolic reality that refers man to transcendence, making him walk in its direction. Every action requires a specific language: the myth, which expresses its condition as a miniature version of the story of the fall and man’s hope of recovering essential justice.

Through the alliance with His people and with each man personally, God Himself reveals about His own being only that, without it, men would not be able to respond to His proposed divinity. He reveals to them everything that makes them become what they are, nothing more.

Man’s actions are interpreted through transcendence and his being should be interpreted likewise, as action proceeds from it (“agere sequitur esse”). Man’s being has a beginning and an end, birth and death. When man finds himself in transcendence, especially by confronting death and the suffering that accompanies it, a big question mark is drawn into his experience of moral obligation. Is there meaning in human freedom—and not whim—if it must suffer and both it and whim are death’s prey? Death and suffering have elevated man to a level that is beyond ethics, where only transcendence can answer the question concerning his own being, which has become “magna quaestio.” Man does not read the answer in his own nature, especially the one he desires.

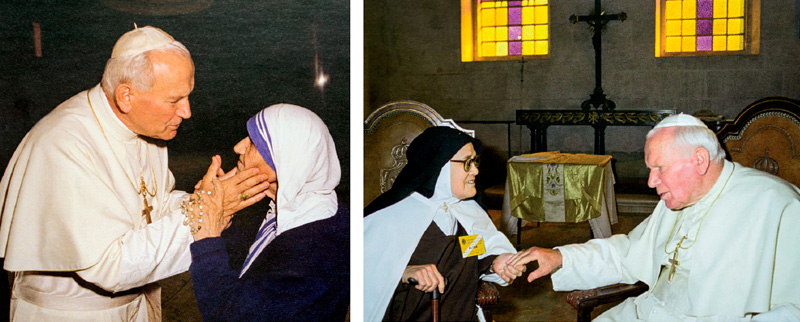

Saint John Paul II with Blessed Teresa of Calcutta and Sister Lucía dos Santos.

Saint John Paul II with Blessed Teresa of Calcutta and Sister Lucía dos Santos.

Through the experience of the moral imperative Karol Wojtyla “read” that particular kind of text that is the nature of the personal being. Without this “text”, man would lack the principle of action, and there could only be a question on what man in general is, but not on what the personal being is.

Job, the pagan of the land of Hus, knew how to read his own nature. He was an intellectual in the deepest sense of the term (from “intus-legere”). By living from the gift of this “text” and not from a hypothesis, he had avoided evil when his life shined bright with the star of success. The outer shape of his actions was no different from those of his friends. Only when he became a victim of misfortune, along with suffering and death, was it evident that Job had “read” man and the world; his friends, on the other hand, only had their own thoughts. Their friendship with Job was formal because they did not understand the fundamentals linked to the beginning and to the end. He, on the contrary, rewarded them with a friendship with which he told them he defended them from themselves. He did not even feel frustrated when what they said hurt him. In fact, he was not faithful to what his friends were, but to what they had to become. By turning into a “magna quaestio” for himself, he became a “magna quaestio” for them.

John Paul II leading the Via Crucis at Rome's Colisseum and saluting the Orthodox Patriarch.

John Paul II leading the Via Crucis at Rome's Colisseum and saluting the Orthodox Patriarch.

Trapped inside their own thoughts, Job’s friends did not understand that the “text” written by God in man is the text of a laborious freedom and a difficult birth. They had been frightened by the vehemence of Job’s questions to God. According to them, Job uttered blasphemies against God. They did not think for a second that Job could have been defending God from their impious thoughts. So great was their idolatry in their theological reasoning, grown in solitude and, thus, outside the dialogue with God.

Idolizing, theological reasoning offends God and negates man. Whoever experiments its influx loses the capacity of sharing his thoughts with others. It is not strange, then, that such a person cannot tremble over death and another’s suffering. Why?

It is only possible to participate in someone else’s suffering and death if such is considered within the perspective of transcendence, which is common to all. Reading the same text is a condition for the dialogue. In order to read man’s nature and not one’s own thought about an argument, it is necessary to reach man’s concrete being, that is, his person. We have to reach our desire for transcendence, which makes us “capaces Dei.” The person is united with love and his desire is understood only in the light of hope. Only by believing in God is it possible to believe in the person of man without the risk of disappointment. He who reads the person’s nature in this way participates in the difficult birth. Let us remember that the word nature comes from the Latin “nascor,” I am born, whose future participle points to something that must be born.

Job’s friends did not understand the nature of the human person because they had done without the experience of suffering and death. They continued thinking outside hope, so, instead of reading the nature of their own being together with He who writes it, they created monologues. Their rationalism prevented them from offering anything to Job. And he was not interested in the exchange of opinions, but in the dialogue with gifts, which to him would have been their words if they had been endowed with such gifts. Empty words were unacceptable to him. His words, on the contrary, were full of presence and that is why God was able to receive them.

There was a separation between ethics and salvation in the ethical thinking of Job’s friends because they did not know the gift. In their reasoning, each of them built a sort of ethical monologue that was an adaptation of God, transforming Him into an idol. All idolatry is the product of an ethics that, not basing itself on the person’s being as desire of transcendence but on the passions that enter it, looks for a way beyond what is ethical to adapt itself to man’s conscience.

As he found himself in the ray of light cast by suffering and death, Job understood the substantial insufficiency of an ethics that is not inspired by the reading of superhuman objectives in man’s nature, that is, in the reading of the presence of the transcendence that comprises it. This does not mean that Job did not acknowledge the need of an ethics. More so, it was precisely at that moment that it acquired importance to him. However, while he found the answers to ethical questions in himself, he had to seek Salvation outside of himself. In the light of Salvation, Job, so bound by ethics in his life, became a question. If there is no answer to the soteriological question, the answers to ethical questions have no meaning: they are mere moralisms [empty moral speeches].

The question of salvation determines the existence, or not, of the ethical questions’ context, even when it is not located within that context. The question over Gift places ethical questions in a context forever endowed with meaning. Man decides his fate inasmuch as he lives in hope, which allows him to move toward the direction his desire tends.

Karol Wojtyla’s pondering was not limited to ethical questions because he possessed a consciousness about man, that is, of his personal bond with God, who entrusts truth and goodness to his freedom. In his ethical questions we find the question of the transcendence of the human person. These questions set up the context of the human person’s actions, and each of them is man’s answer to its categorical call and non-verification of ephemeral ethical hypotheses.

We must not be surprised, then, by the easiness with which ethical questions, in Karol Wojtyla’s thinking, overlap with the question of grace. They form an organism in which the question of man’s divine past, which allows him to understand his own present sin, comes together with the hope of recovering everything he has lost. The encounter between these two questions gives rise to the anthropology that cardinal Wojtyla will eventually call proper anthropology.

Karol Wojtyla’s anthropology led to John Paul II’s testimonial thinking. I allow myself to point out that, somehow, he must have sensed where the path he was following would take him.

Karol Wojtyla entered Peter’s order as John Paul II, where man’s “magna quaestio” meets the “Magna Quaestio” that is Christ. Karol Wojtyla’s pondering on man goes back to “ad Christum Redemptorem,” by permanently returning to the foundations of being and action, united now to the communion of people entrusted to him by Peter.

With the liberty that can only be permitted to the love thrice confessed to Christ, John Paul II speaks of him as the divine answer to man’s question on the transcendence of the beginning and the end. While he gives testimony to Christ, he not only gives a testimony about Salvation, but about God’s Creation through his Son. John Paul II does a sui generis “reduction” of man to the Son of God.

In him, as it is always said, the realization and defense of the human person is found. In fact, Christ was sent to man as God’s great question, calling the human person to a dialogue that transfigures him. Only he who thinks about this question and defends it continuously returns to Christ as Beginning and End.

Ethical foundations protect man from evil and with the foundation of Christ man is protected from himself.

By bearing witness to the act of creation, John Paul II bears witness, through faith, of the divine definition of man, without which one could not speak of the truth and action of his being. Thinking means searching for this Definition with all one’s being, because in it we may clearly find every man’s identity. The thought that creates it is God Himself. Thus, searching for the definition of one’s own being is to look for Him in one’s own realization, i.e. Salvation. It is useful to understand the definition of the truth of knowledge not as “adaequatio intellectus cum re,” but as the coherence of man’s human person with the nature of being, known by means of the first. In this acceptance of the truth, knowledge is love and love is knowledge. The man that seeks such a truth becomes that and gradually experiences in a smaller degree the pressure that acts outside the dialogue between his own freedom and God’s freedom. Proper anthropology protects human thought from servility and human subjectivity from the invasion of the objective world.

In Peter’s testimony there is man’s truth, saving him. Here, man, who asks God about himself, receives Christ’s person. In him, the anxious question of man about himself develops and matures in the question of God. Mercifully oriented towards the human person through the act of the Incarnation, it is introduced in the dialogue that is his inner life. The dialogue with God frees the human person of all that is not God.

In the question-testimony given to Christ by Peter, man appears as a judged being who knows where Peter’s question should aim: “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (Jn 6:68). A man that has been judge as Peter was, cannot and must not judge everything.

Therefore, it is not surprising how determined John Paul II is in emphasizing that no human will, even with a majority supporting it, has the right to decide over human freedom, i.e. over his knowledge and love. No human will has the right to decide over his rights and duties, because they do not come from political decisions, but from an identity devised “in the heavens before the making of the world.” Nothing can decide over the birth or death of a conceived human being. This, in fact, comes from beyond, where calculations of human intellect and the technical capacity of his hands cannot reach: the place where man comes from and that can only be reached by man’s love and hope, together with the song that express them. There can only be song about love and hope and they are not submitted to vote.

John Paul II’s intransigence which reminds us that the human person has already been judged in Christ, in the acts of creation and redemption, inevitably awakens criticism in all who, for different reasons, do not want to acknowledge God’s authority.

By starting his catechism with a reflection on man’s creation and resurrection, John Paul II defends the human person’s body by arguing that its meaning comes from the love that unites two people. This union is not only physical, but the union of the two bodies’ beauty, and it is not a matter of possession, but something destined to be. In this union, by generating one and the other, they create the space for a new gift: the human person. The meaning of the body is expressed in its beauty, transforming the whim of man’s immanence into freedom.

Friendship, marriage, families, and nations are born from this freedom-love. This is what John Paul II refers to when he speaks of society. On the other hand, when he speaks of the State he refers to something that must be defined and guarded. A state that does not achieve these essential duties is not worth the name; it is but a parasite to man. It is not politics or economics’ responsibility to decide over a person’s service to people, but it is the responsibility of the person’s service to people to decide over politics and economics. If politics and economics were the basis of love and freedom, instead of the other way around, the person, together with his friendship, marriage, family and society, would be mistreated. Injustices originate from this misconception.

John Paul II defends the human person, marriage, the family and society itself from the lack of reflection of a whim that looks like freedom, but which is not so. The individual’s freedom, which is his faithful love, is protected by the truth that is inscribed in the act of man’s creation and resurrection. When the “text” of the human person’s nature is not read, coexistence among men occurs as a struggle that often develops into conflict. War makes evident the lack of preoccupation for that which makes the individual person, people, and societies, what they are.

Man, transformed into a question of the transcendence of the beginning and the end, stays in the past by means of love and resides with love in the future by means of hope. Because of these virtues, it measures present things with those that are far away. The present is not suspended over a void created by the past and the future. In the dialogue from which God’s people arises, man dominates the present and responsibly makes history.

The memory of the past and the future surpasses man’s historical memory. It is the memory of his divine origin and, moreover, of his divine destiny. Man, in his condition as created entity, living prophetically, receives the Word-Coming that is Christ. It is given to him so that the divinization of his created being is produced in him. This divine-human dialogue is realized in the dialogue among humans, where man welcomes another and gives himself to him in return. The concept of incarnate coming cannot be understood without it being word-coming and vice versa: being word-coming can only be understood in the light of Incarnation. The coming of the divine word into the coming of human words is what we call tradition. Words that do not find their place are dead, or not born.

The coming in the path towards the superhuman word implies existing disinterestedly from birth to death. The less selflessness there is among men, the greater the risk of them understanding each other and viewing birth, death, friendship, marriage, and society in the same way they view products administered according to market rules.

The gift is realized when it is received. So it happens with birth and also man’s death. He who is a gift waits for love to receive him. Men who live by calculations fail to understand words that have not been calculated. Only love can speak with love. No one can be forced to give a gift and no one can be forced to accept it. That is why, if birth and death are attained through technology, by not being acts of freedom and love, they radically hurt the person. The society that has forgotten the principles of freedom and love will only create a history of the production of life and death, a history of radical injustice.

John Paul II’s reflections on what occurs to man in the act of creation, and in the end, in the act of Resurrection, finish, according to a natural succession, with a reflection on man’s emancipation from injustice, i.e. in the history of his heart. John Paul II dedicated the third part of his catechism to this history.

Man’s heart is restless, and because of this it cannot be the starting point or the finish line for its own work. In the history of man, God’s Transcendence is manifested as an incomprehensible union of truth and love, Justice and Mercy. There is no doubt that the categorical moral obligation imprints a direction in that history. It begins with the mystery of sin that hurts man’s nature without destroying it, so that he can remember that he used to be different… The instinct of self-defense speaks in it. Man immediately and spontaneously defends himself. Just as his thought, his ethical effort, expresses itself in a daily metanoia, with the hope of finding salvation in the transcendence he is drawn to.

John Paul II looks at the dramatic history of the human heart through the dramatic history of Christ. As he thinks about man, he thinks about Christ, and vice versa. When he repeats Peter’s words in the name of everyone, “Lord, to whom we shall go? You have the words of eternal life. We have come to believe and to know that you are the Holy One of God” (Jn 6:68-69), he is thinking about man as someone who is destined for divinity and of Christ as someone who is “destined” to humanity. It is not by coincidence that his first encyclical begins with these words: “The ‘Redemptor hominis’ is the center of the universe and history.” In this center, justice is identified with mercy and mercy with justice.

John Paul II thinks about the history of the human heart through grace, which grows where there is sin and where man is as weak as defective wood and iron… It knows what sin is because it knows what grace is. With no consideration to the misery of time, it reveals duties to man that he will not understand if he continues to look at himself in the light of his own sin. I believe that men who are slaves to contemporary civilization feel offended by this Pope because they do not search in grace the criterion to think about themselves and society, but in sin.

John Paul II also thinks about the human person’s sociopolitical life in the light of grace. Together with the proclamation that the integration of the person, and therefore also the integration of society, is not realized in a doctrine, but in the person of Christ, John Paul II defends man and society from all kinds of totalitarianism that force men into accepting idolizing and mortifying behaviors and, thus, expressing themselves with hypocritical gestures in which nobody reveals himself.

Social justice reigns where there are just men, that is, where free men act, moved by the desire of something transcendent that allows them to be even more than themselves. The transcendence of the objects around which man moves does not lead to freedom. By promising to participate in someone else’s life, only the grace of love gives what is transcendent to him who aspires for it. Every gift of these free men is a sign and presence of the supernatural gift without which there is no justice.

He who chooses the criterion of freedom in the struggle for liberty is mistaken. Experience teaches that sooner or later we only become sensitive to cold and heat.

Politics and economics, practiced without remembering the grace of truth and mercy, in the characteristic oblivion of man’s weakness and sin, cease to generate peace and justice, because they do not integrate people. They just create situations where lies and sin are disguised by a simulation of truth and virtue. In the situations of lies and sin, “ars gobernandi” degenerates into “ars dominandi.”

Aware of the fact that the drama of man’s heart history is solved in the encounter with his weakness and sin and grace, John Paul II reminds the rich and the poor of human weakness and divine grace. He does not defend the poor against the rich. If he defended them, he should also defend the rich against the poor. He would enter a dialectic in which the master strikes the servant and the latter, in turn, does not look at the master with love, especially when he is in his hands. Master and servant are caricatures of the human person, and their struggle to achieve better positions in this dialectical society is just a squabble, sometimes inflamed, between impulsive and irresponsible children.

TESTIMONIES AND TESTAMENT

Testimony of Benedict XVI

“How can we sum up the life and evangelical witness of this great Pontiff? I will attempt to do so by using two words: "fidelity" and "dedication", total fidelity to God and unreserved dedication to his mission as Pastor of the universal Church. (…).With his words and gestures, the dear John Paul II never tired of pointing out to the world that if a person allows himself to be embraced by Christ, he does not repress the riches of his humanity (…).

The love of Christ was the dominant force in the life of our beloved Holy Father. Anyone who ever saw him pray, who ever heard him preach, knows that. Thanks to his being profoundly rooted in Christ, he was able to bear a burden which transcends merely human abilities: that of being the shepherd of Christ’s flock, his universal Church.”

Testimony of Pope Francis

“He was ‘the great missionary of the Church’: he was a missionary, a man who carried the Gospel everywhere, as you know better than I. How many trips did he make? But he went! He felt this fire of carrying forth the Word of the Lord. He was like Paul, like Saint Paul, he was such a man; for me this is something great.”

Prayer of Mother Teresa

“Under the weight of the Cross the Pope, following the example of Jesus, teaches us to ‘love’ the Cross. The Cross of the Christian is always a Holy Cross: teach us, O Lord, to learn to stay under the sign of the Cross. After the Cross, O Lord, comes the radiant dawn of the Resurrection. Our Holy Father already encountered this dawn of Resurrection in May of 1981after vanquishing the dark night of that tragic event. As then, so today, the Pope will return to serve the Church, having once again loved it at the foot of the Cross. (…) For us the Holy Father is presence, is grace, Is hope, is certainty. May our certainty, O Lord, not be damaged. In moments of suffering and hardship. We thank you, O Lord, for all the good that you wish for us.”

The Testament

“The times we are living in are unspeakably difficult and disturbing. The Church's journey has also become difficult and stressful, a characteristic proof of these times - both for the Faithful and for Pastors. In some Countries, the Church finds herself in a period of persecution no less evil than the persecutions of the early centuries, indeed worse, because of the degree of ruthlessness and hatred. Sanguis martyrum - semen christianorum ["The blood of martyrs is the seed of Christians" (Tertullian)]. And in addition to this, so many innocent people disappear, even in this Country in which we live.... I would like once again to entrust myself entirely to the Lord's grace. He Himself will decide when and how I am to end my earthly life and my pastoral ministry.

In life and in death [I am] Totus Tuus through Mary Immaculate. I hope, in already accepting my death now, that Christ will give me the grace I need for the final passover, that is, [my] Pasch. I also hope that He will make it benefit the important cause I seek to serve: the salvation of men and women, the preservation of the human family and, within in it, all the nations and peoples (among them, I also specifically address my earthly Homeland), useful for the people that He has specially entrusted to me, for the matter of the Church and for the glory of God Himself.”

(Spiritual Testament of Saint John Paul II)

My beloved city

“As the end of my earthly life draws close, I think back to its beginning, to my Parents, my Brother and my Sister (whom I never knew, for she died before I was born), to the Parish of Wadowice where I was baptized, to that city of my youth, to my peers, my companions of both sexes at elementary school, at high school, at university, until the time of the Occupation when I worked as a labourer, and later, to the Parish in Niegowic, to St Florian's Parish in Krakow, to the pastoral work of academics, to the context... to all the contexts... to Krakow and to Rome... to the persons who were especially entrusted to me by the Lord. I want to say just one thing to them all: "May God reward you!" “In manus Tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum”, A.D. 17.III.2000”.

(Spiritual Testament of Saint John Paul II)

Chronological Biography

1920, May 18. Karol Józef Wojtyla is born in Wadowice, Poland, son of Karol Wojtyla and Emilia Kaczorowska.

1929, April 13. His mother dies.

1938, August. He moves with his father to Krakow and is enrolled in the Faculty of Arts of the Jagiellonian University.

1941, February 18. His father dies of a heart attack. Karol is left alone and starts working as a laborer in the quarry of Zakrzewek.

1946, November 1. He is ordained to the priesthood in Krakow and shortly after travels to Rome to continue his studies in theology.

1958, July 4. After three years of study, he is appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Krakow.

1964, January 13. He was appointed Archbishop of Krakow.

1967, June 26. He is made Cardinal by Pope Paul VI.

1978, October 16. He is elected Pope.

1979, June 2-10. He makes his first Pastoral Visit to Poland.

1981, May 13. An assassination attempt on his life takes place at St. Peter’s Square, with two successive hospitalizations at the Gemelli Hospital which he finally leaves on August 14.

1983, June 16-25. Second Pastoral Visit to Poland, where the martial law is in force.

1986, October 27. He presides over the First World Day of Prayer for Peace convoked in Assisi with the representatives of the Christian Churches and the religions of the world.

1988, July 2. He ratifies the full ecclesial ex-communion of priests who were linked to the traditionalist Fraternity founded by Bishop Marcel Lefebvre.

1992, October 31. End of the “revision” of the Galileo Galilei case with the “loyal apology” for the wrongdoings which the erudite had suffered.

1999, December 24. He opens the Holy Door of Saint Peter’s Basilica and starts the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000.

2005, February 24 – March 13. He is admitted at the Gemelli Hospital due to a respiratory crisis and is operated of tracheotomy.

2005, April 2. He dies at 9:37 pm. in the Vatican.

2011, May 1st. Pope Benedict presides over his beatification.

2014, April 27. Pope Francis proclaims him SAINT.

For this reason and none other, John Paul II decisively said “No!” to theologians that look at man’s life and society through the perspective of feelings born from difficult political and pastoral experience. Even though they have nothing but noble intentions, when those feelings are left to themselves, they end up at the mercy of the servant-master dialectic, which is always totalitarian.

Cardinal Ratzinger, future Benedict XVI and- in that time -Dean of the College of Cardinals, presides Saint John Paul II's funeral.Using Norwid’s language, we would say that John Paul II “descends” to “human questions” about man considering the question about the person of Christ. “Human questions” in which Christ’s prophetic trace is not present, are merely technical and, more or less efficaciously, treat their own being and others as objects. Objects are desired. The chaos of man’s desire, provoked by the lordship of reason and will’s servility for pleasure and comfort, destroys friendship, marriage, families, and societies.

Cardinal Ratzinger, future Benedict XVI and- in that time -Dean of the College of Cardinals, presides Saint John Paul II's funeral.Using Norwid’s language, we would say that John Paul II “descends” to “human questions” about man considering the question about the person of Christ. “Human questions” in which Christ’s prophetic trace is not present, are merely technical and, more or less efficaciously, treat their own being and others as objects. Objects are desired. The chaos of man’s desire, provoked by the lordship of reason and will’s servility for pleasure and comfort, destroys friendship, marriage, families, and societies.

It is common to speak of John Paul II’s great strategy and his ability in ousting “adversaries.” There is as much truth in this as there is misunderstanding. The strategist wins because he looks at the case from a higher level. John Paul II’s thinking travels from man in his beginning until his end, therefore including God’s surprises for us. God comes to us when we least expect Him.

John Paul II does not accept battles over the human person on the grounds of chaos. He always takes the battlefield to a higher level, where man’s reality, disintegrated in senseless fragments, is reconstituted in a beautiful landscape. The ultimate battlefield for man is the Cross. In it, John Paul II looks for the reintegration of the human person and society. In front of this “magna quaestio” of God and man “the thoughts of many hearts will be revealed” (Lk 2:35), and therefore his freedom and order, but also his desire and chaos. Thus, the feelings in Job’s heart and his wife’s and friends’ hearts were expressed while facing suffering.

When we say “person”, we mean communication of the persons. In the union of the beauty of human bodies, which happens with God and not of themselves, God’s people is born, so the “magna quaestio” becomes the “magna quaestio” of society. Events in human society always happen in the same way they do in the society of divine persons. Every person is love. A society without persons becomes a mere sum of individuals in a mass.

The space of the interpersonal dialogue of love, to which God’s word gives life, is the Church’s space, in the widest sense of the term. The Church does not postulate ideological or doctrinal opinions and hypotheses; she is concerned with being present among men, creating a divine-human friendship through which we grow. The Church shows the person of God to the human person. That is why the Church, even when it exists in it, is different to this world. Beyond its serious moral shortcomings, she is an authority for the world and not the other way around.

If society cannot do without persons and persons cannot do without the Church, nothing in social life can replace the Church. The Church is not only concerned with man, but also with society. That is the reason why social doctrine is necessary in the Church and she releases encyclicals like “Centesimus annus.”

The Church—John Paul II says—must not create civilization or serve one system today and another one tomorrow. The Church, in fact, does not arise from that or is directed towards that. It ministers to the special vigil of the people in the presence of God’s gift.

The Church, which must show the person of Christ to the human person, cannot prevent suffering or death from occurring. If it did so, it would cease to protect and there would be no act of adoration in a world where the coming is realized in the Church. Man would not live in spirit and truth.

The absence of suffering and death cannot be anything but a cosmic tragedy, a tragedy of the individual person and of the people. Christ severely reprimanded Peter when he tried to convince him not to enter Jerusalem, where he was to suffer and die. He openly called him Satan because he felt according to man and, therefore, against man.

John Paul II’s reflection on man is a difficult one, because, with Christ, he watches over the human suffering that rises from life. It is the reflection that Job’s friends fail to understand. Nevertheless, in his prayer Job gained consciousness and acted in harmony with its own nature to save them; he trusted God. “No man is an island.”

Translated by Ana María Neira