Was J.R.R. Tolkien a modern writer? The author of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion is undoubtedly “modern” in the sense that he lived in our own historical period (he died in 1973). Furthermore, his writing is extraordinarily popular with modern readers. But critics often allege that he was not modern but rather pre-modern in his approach to literature, and certainly they are right in the sense that it was ancient storytelling traditions and Anglo- Saxon literature such as Beowulf that particularly inspired him. His book contained many archaic elements. It was not, however, archaic or pre-modern in itself. The Lord of the Rings is a novel with modern concerns. It could not have been written in an earlier age. It contains an implicit but very strong critique of modernity – of aspects and tendencies of the modern world – such as globalization, socialism, and reliance on technology. But is this regressive or progressive? Only time will tell.

Who Was Tolkien?

But first, who was this man, this writer? Like every one of us, he was more than the sum of his parts. As a child he became an orphan – his father died when he was four, his mother (a Catholic convert reduced to poverty by the resulting exclusion from her family) when he was twelve. Later he became an Oxford don, a professor of Anglo-Saxon. He worked on the Oxford English Dictionary. He translated the Book of Job for the Jerusalem Bible. He cycled to Mass nearly every day. In the evening he made up stories for his four children. People say he dressed up like an ancient warrior with horns on his head wielding a big axe to chase tourists out of his garden. He was a bit like an overgrown hobbit, with his fancy waistcoats and his pipes of tobacco. (In fact he once described himself as a “Hobbit in all but size.”) And he was very like a wizard in his old age, casting a magic spell with his words over millions of readers.

In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day and more than a million lives on both sides were lost altogether. The experience helped to make him a writer, as it did the war poets Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, and Siegfried Sassoon, and in the next war the fantasy writer T.H. White, author of The Once and Future King. In later years, looking back, Tolkien described how the early writings about Middle-earth and some of his made-up Elvish languages began as a distraction when he was supposed to be paying attention to being a good officer in the War: “in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle-light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire” (L. 66).1 He wrote fantasy, he said, in order to express his feelings about good and evil, fair and foul; to make sense of them, and prevent them “just festering.”

In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day and more than a million lives on both sides were lost altogether. The experience helped to make him a writer, as it did the war poets Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, and Siegfried Sassoon, and in the next war the fantasy writer T.H. White, author of The Once and Future King. In later years, looking back, Tolkien described how the early writings about Middle-earth and some of his made-up Elvish languages began as a distraction when he was supposed to be paying attention to being a good officer in the War: “in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle-light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire” (L. 66).1 He wrote fantasy, he said, in order to express his feelings about good and evil, fair and foul; to make sense of them, and prevent them “just festering.”

Another aspect of Tolkien might surprise you: Tolkien as Romantic Lover. He fell in love in 1909 at the age of sixteen with a pretty girl called Edith Bratt who was three years older than him, also an orphan, but a Protestant. His guardian by that time, the rather strict Father Francis Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory, forbade him to see or speak to her until he came of age at twenty-one, and he obeyed fairly well – except for a couple of clandestine meetings early on, which got him into trouble, and some accidental encounters later – with the result that by the time he finally wrote to ask her to marry him, on the evening of his twenty-first birthday, she had become engaged to someone else, thinking Tolkien had forgotten her. Luckily she was still in love with him and willing to break off the engagement. In 1914 she reluctantly converted to Catholicism (in those days mixed marriages were not permitted in a Catholic church), and in 1916 they married in the Church of Mary Immaculate in Warwick. Despite occasional tensions2 it was a remarkable lifelong romance, and left its mark on Tolkien’s writing in several ways.

If you have read The Lord of the Rings or seen the movie, you’ll remember the love story concerning Aragorn and Arwen. In Tolkien’s writing, this harks back to an earlier romance between Man and Elf, many thousands of years earlier – the story of Beren and Lúthien, the ancestors of both Aragorn and Arwen. Wandering in the summer in the woods of Neldoreth, he writes, the man Beren came upon Lúthien, the princess of the Elves,

at a time of evening under moonrise, as she danced upon the unfading grass in the glades beside Esgalduin. Then all memory of his pain departed from him, and he fell into an enchantment; for Lúthien was the most beautiful of all the Children of Ilúvatar [the Elvish name for God]. Blue was her raiment as the unclouded heaven, but her eyes were as grey as the starlit evening; her mantle was sewn with golden flowers, but her hair was as dark as the shadows of twilight. As the light upon the leaves of trees, as the voice of clear waters, as the stars above the mists of the world, such was her glory and her loveliness; and in her face was a shining light.

Beren falls instantly in love, and asks for her hand in marriage. Her father sends him on a seemingly impossible quest, in which (though only with Luthien’s help) he succeeds. Eventually, however, he is killed and she descends into the underworld to rescue his soul. She sings so beautifully to the Lord of the Dead that both are restored to life for a brief time. It is a beautiful story, right at the heart of Tolkien’s writing, but the romance he was describing was in a way his own – a kind of mythological statement about what it felt like to fall in love at first sight, how love can reshape one’s entire life, and how husband and wife achieve the Quest together or not at all. Tolkien and Edith are buried together in Oxford, and on their tombstone he had the names engraved of Beren and Lúthien.

Finally, of course, Tolkien was a master of languages. His friend C.S. Lewis, in an obituary, even wrote that Tolkien unlike other, more superficial linguists, had travelled “inside” language, like an explorer penetrating a barrier and finding a place no one else had been. He understood the music and the meaning of language, and the way it evolves through time, perhaps better than anyone else before or since. Already as a teenager he knew most of the main European languages, ancient and modern. In school debates he was happy to speak in Latin, Greek, Gothic, or Anglo-Saxon instead of English. Later he came to love Finnish and Welsh particularly.

And of course he soon started to make up new languages of his own, although he began to think of them not so much as inventions but as reconstructions of old languages that might have existed before the ones we know, going back to a mythological time before history, a time when elves and dragons walked the earth. Middleearth, you could say, was constructed partly as a setting for these languages – to imagine a world in which it would make sense that people spoke Elvish not English.

Tolkien and Modernity

Each of the elements I have been describing in Tolkien’s make-up – soldier, lover, linguist, and Catholic – specifically contributed to his critique of modernity, and I will say a brief word about each in turn.

Soldier

«In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day.»

«In his youth he was a soldier – an officer in the Lancashire Fusiliers, fighting in the trenches of the Somme in 1916, where 60,000 British soldiers died on the first day.»

First, through fighting in the War he became very aware of the sudden onset of the modern age, marked by the use of weapons of mass destruction and the increasing mechanization of warfare – but at the same time he learned to appreciate the moral virtues of the ordinary English soldier alongside he was fighting, the English “tommy,” as he was called. In fact the character of the lovable, unpretentious, and yet indomitable working-class Sam Gamgee is a portrait of the men he got to know in the trenches of the Somme – a ruined landscape, by the way, which bore a marked resemblance to the Dead Marshes through which Frodo and Sam are led by Gollum on their way to the Black Gate of Mordor. His account of the Fall of the hidden Elvish city of Gondolin was begun at this time, and describes an assault by Orcs and Balrogs, “dragons of fire” and “serpents of bronze and iron”, under great steams and smokes that must have been partly inspired by his experiences on the Front. Later, The Lord of the Rings was written during the Second World War, in which his son Christopher served, a war fought against a great dictator who was seeking to bring the whole world under his dominion – and yet a war that was eventually won by the use of tactics and technology that Tolkien abhorred, for example the fire-bombing of Dresden and the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He calls it “the first War of the Machines”, which will leave everyone the poorer, millions dead, “and only one thing triumphant: the Machines” (L. 96). After the War, he prophesied, “the Machines are going to be enormously more powerful” – prompting him to ask: “What’s their next move?” (ibid.).

In his published Letters, Tolkien refers to the “tragedy and despair” of modern reliance on technology, when it alienates us from the natural world. In the novel, this tragedy is vividly illustrated in many ways, not least by the corrupted wizard Saruman, with his “mind of metal and wheels.” In the modern world, with its ecological disasters and its factory farms, we have seen the devastating and dehumanizing effects of Saruman’s purely pragmatic approach to nature. The English Romantic movement, from William Blake and Coleridge through to the Inklings, believed there must be an alternative. At the end of his wonderful essay The Abolition of Man, which everyone ought to read, Tolkien’s friend C.S. Lewis writes hopefully of a new kind of science, a “regenerate science” of the future that “would not do even to minerals and vegetables what modern science threatens to do to man himself. When it explained it would not explain away. When it spoke of the parts it would remember the whole.”

For modern science, on the other hand, Lewis argued, as for the old black magic that never really worked, the goal is power over the forces of nature. That power is sought for a variety of reasons, some good, some bad. We may wish to satisfy our curiosity and increase our knowledge of how the world works. We may wish to do wonderful things with our new-found power over nature: end poverty, extend life, heal disease. We may simply want to win a Nobel Prize. But what Lewis calls the “magician’s bargain” tells us what the price of such power may be: namely, our own souls. In fact, he says, the conquest of nature turns out to be our conquest by nature, that is to say, by our own desires or those of others (those who end up controlling the machinery). Only those who are masters of their desires, and not driven by them, can really be called powerful or free.

Tolkien explores two different types of technology, two different understandings of science, through the contrast in his story between the Elves and the Enemy: the science of the Elves (called “magic”) has not been separated from art as it is in our day; indeed, it could be called a form of art. If the goal of the Elves is Art, the aim of the Enemy is what he calls the “domination and tyrannous reforming of Creation.” The devices of the Elves, like the magic Ring worn by Galadriel to protect Lothlórien, are all more or less benign. They work “with the grain of nature,” not against it. The science of the Enemy, in Tolkien’s world, is very different. It reflects a desire to control. The will to power, he writes, “leads to the Machine”: by which he means the use of our talents or devices to bulldoze others into submission. The Ring of Power, the “One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them,” is an example of this kind of technology. And he is realistic when he shows the biggest temptation to use the Ring is felt by those who persuade themselves they want to do good rather than evil – to make the world a better place by bending it to their own will.

Of course, when we get into the task of “locating” the Ring, or what is left of it, in the present world, I should mention that Tolkien always insisted that his fantasy was no mere allegory. Mordor was not a thinly disguised Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia. He once wrote: “To ask if the orcs ‘are’ communists is to me as sensible as asking if communists are orcs.” But at the same time he did not deny that the story was “applicable” to contemporary affairs, indeed he affirmed this. It is applicable not merely in providing a parable to illustrate the danger of the Machine, but in showing the reasons for that danger: namely the ever-present vices of sloth and stupidity, pride, greed, folly and lust for power, all exemplified in the various races of Middle-earth.

This important lesson that Tolkien drew from the War –that evil must not be done for the sake of the good– has many important implications. Even the Orcs, who appear utterly evil and who “must be fought with the utmost severity,” Tolkien writes in one of his notebooks, “must not be dealt with in their own terms of cruelty and treachery. Captives must not be tormented, not even to discover information for the defence of the homes of Elves and Men. If any Orcs surrendered and asked for mercy, they must be granted it, even at a cost.” In recent years and months we have seen the British and American secret services put on trial for allegedly flouting this principle and torturing prisoners. Tolkien’s parable remains instructive on many levels.3

Lover

Earlier I said that Tolkien’s romance with Edith – his role as romantic lover – was itself a basis for his critique of modernity, and it is time to explain what I meant by that. Bear in mind that in writing these stories he was not constructing an “escape” from everyday reality, as critics allege by calling this kind of thing “escapist” literature. He was trying to show, albeit in an exaggerated and imaginary form, the way the world really works, both morally and spiritually. The actor who played Aragorn in the movie, Viggo Mortensen, when asked why the film and the book were so popular, replied that he thought it was because they tell a “true story.” He was right. There is truth in the story, and that is what makes it so interesting. But by building romance into the mythology the way he did – and this only becomes obvious when you read The Silmarillion as well as The Lord of the Rings – Tolkien was affirming that all of history is in the end a love story; that love is the most important thing in the world – it is not just what shapes the world, but the thing for the sake of which everything happens. Not just the love of man and woman, of course, but also the love of friends and the love of beauty and the love of life that comes to a kind of crescendo in the fruitful love of marriage.

Take The Lord of the Rings itself. Frodo’s Quest to destroy the Ring begins with his desire to save his beloved Shire from the Shadow that threatens to engulf it. It is the love of his friends that creates the Fellowship which achieves the Quest. Each member of the Fellowship plays a part. Through that adventure, the Hobbits grow up. They learn the virtues of courage and fidelity and wisdom that are needed to heal the Shire of the evil that infects it when they return. (Very unfortunately this part of the book was omitted in Peter Jackson’s film.) And Sam in particular – who is in a way the hero of the story, almost more than Frodo according to the author – acquires through these adventures the maturity and courage to propose to his beloved Rosie, and settles into Bag End as Frodo’s heir, before long with a big family. The Lord of the Rings ends with his return from the Grey Havens:

And he went on, and there was yellow light, and fire within; and the evening meal was ready, and he was expected. And Rose drew him in, and set him in his chair, and put little Elanor upon his lap. He drew a deep breath. “Well, I’m back,” he said.

With this ending, Tolkien was making the point that all the high epic adventures in Rohan and Gondor and Ithilien, all the battles and torments that the Hobbits had gone through at the hands of the Orcs and on the fields of the Pelennor, were for the sake of the Shire, to enable the Hobbits not only to defend and heal it, but in the case of Sam, to settle down into ordinary domestic life.

The Shire, of course, represents the England that Tolkien loved, the villages and fields that he played in as a child, and the horrible slum ruled by Saruman that they find on their return is a vision of what modernity has done to that English idyll 4. You could say that the lesson of the story is that ordinary life, and especially marriage and family today, needs to be protected and supported not just by external armies but from within, by a life of heroic virtue, or by virtues that would be recognized as heroic if projected onto the big screen of an adventure far from home, because there they can be seen for what they really are.

Linguist

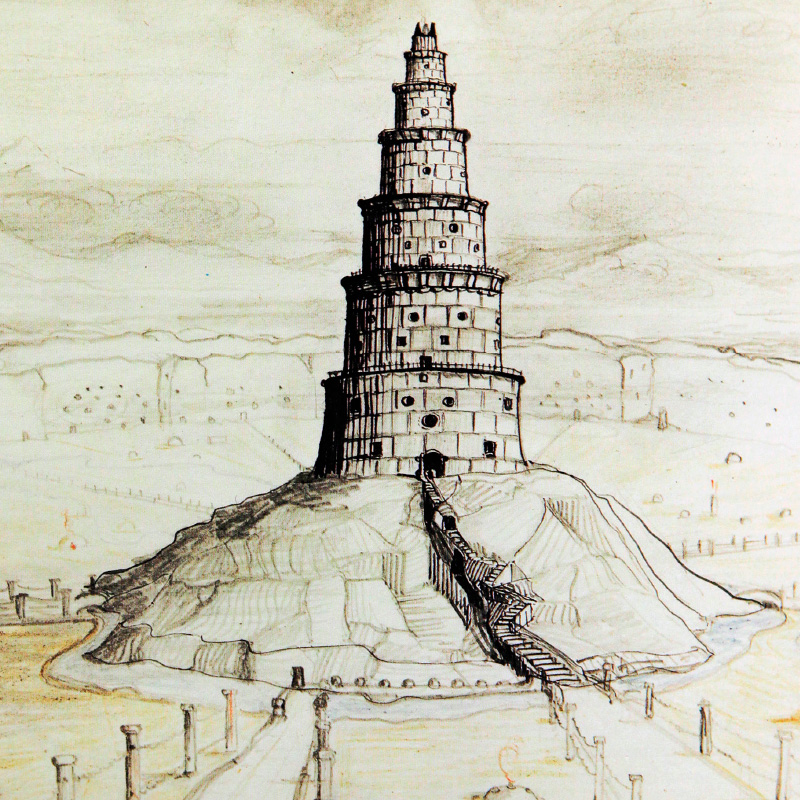

«In his published Letters, Tolkien refers to the “tragedy and despair” of modern reliance on technology, when it alienates us from the natural world. In the novel, this tragedy is vividly illustrated in many ways, not least by the corrupted wizard Saruman, with his “mind of metal and wheels.”» Tolkien’s drawing of the Tower of Isengard (Orthanc).

«In his published Letters, Tolkien refers to the “tragedy and despair” of modern reliance on technology, when it alienates us from the natural world. In the novel, this tragedy is vividly illustrated in many ways, not least by the corrupted wizard Saruman, with his “mind of metal and wheels.”» Tolkien’s drawing of the Tower of Isengard (Orthanc).

As for Tolkien’s love of language as a source for his anti-modernity, it is bound up with his love of tradition, of history, and of folklore. The evolution of languages cannot be separated from the evolution of civilizations, and the words we use today give us clues to things that happened, and the way people thought and acted in the distant past. Tolkien wanted to unravel language, and travel back through time to see a lost world, one that predated the histories known to us, so far back that it would appear mythological, enabling him to speak of mysteries such as creation itself, and the origin of good and evil, and the obscure longing that haunts us for a paradise we somehow feel once existed on the earth. “We all long for it,” he wrote (L. 96), “and we are constantly glimpsing it: our whole nature at its best and least corrupted, its gentlest and most humane, is still soaked with the sense of exile.” The sense of longing, of nostalgia for paradise, comes (he thought) from the best part of ourselves, the part that “remembers” its Origin, when we came from the hand of God and were first filled with the breath of life. He was “anti-modern” in the sense that modernity often stands against this kind of yearning with a kind of world-weary cynicism. Such things never were, we are told, and never could be because Man is just an animal like any other, except nastier and more dangerous. Tolkien’s stories say, No! We can look up at the stars, we can aspire to be greater than we are, and if we do this then divine grace will help us. Our very ability to imagine worlds like Middle-earth and the Blessed Lands of the West prove that we are more than these modern cynics choose to believe. In a poem called “Mythopoeia,” inspired by a conversation with C.S. Lewis that led to Lewis’s conversion to Christianity, he summed it up like this:

The heart of Man is not compound of lies, but draws some wisdom from the only Wise, and still recalls him. Though now long estranged, Man is not wholly lost nor wholly changed. Dis-graced he may be, yet is not dethroned, and keeps the rags of lordship once he owned, his world-dominion by creative act: not his to worship the great Artefact, Man, Sub-creator, the refracted light through whom is splintered from a single White to many hues, and endlessly combined in living shapes that move from mind to mind. Though all the crannies of the world we filled with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build Gods and their houses out of dark and light, and sowed the seed of dragons, ‘twas our right (used or misused). The right has not decayed. We make still by the law in which we’re made.

Tolkien’s search for the Beginning of all things was expressed through the invention of mythology, but his desire for it was awoken by the love of language, or rather of the Word – the divine Logos, the Second Person of the Trinity – that he felt he could hear resounding like a kind of distant music in certain phrases in certain languages, such as Anglo-Saxon.5 It was this that in 1914 prompted him to start writing, and he never stopped until his death in 1973. His mythology expresses the very profound intuition that prose begins in poetry, and poetry in song, and song in music, and that music is equivalent to light, which is the primary vibration stirred by the voice of God in the deep waters of existence. So that all of history, like all of cosmology, is the unfolding story of Light and Music, in which God expresses his joy by giving freedom to creatures who sing and shine with him, and by bringing good out of the evil that seeks to engulf the light at every turn.

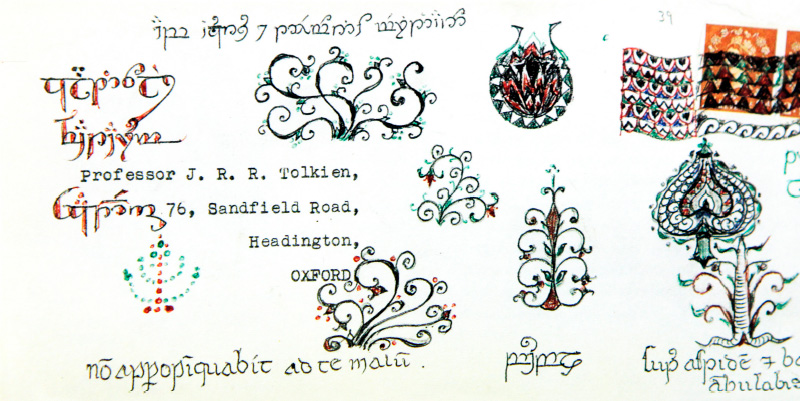

«He soon started to make up new languages of his own, although he began to think of them not so much as inventions but as reconstructions of old languages that might have existed before the ones we know, going back to a mythological time before history, a time when elves and dragons walked the earth.» Envelope with Tolkien´s elvish writing.

«He soon started to make up new languages of his own, although he began to think of them not so much as inventions but as reconstructions of old languages that might have existed before the ones we know, going back to a mythological time before history, a time when elves and dragons walked the earth.» Envelope with Tolkien´s elvish writing.

Catholic

And so we come to the fourth and final point, Tolkien’s Catholicism. How much more anti-modern can you get, than to be a Roman Catholic? Or rather, to be a Catholic of Tolkien’s kind, traditional and orthodox and devout, in the end submissive to Rome even when it changed the liturgy he loved, faithfully upholding the supreme value of the Real Presence (L. 250), and even the unpopular teaching on marriage? Of course, The Lord of the Rings makes no reference to religion, and is even less obviously a Christian work than C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. Nevertheless, in 1953 Tolkien admitted to a Jesuit friend, Robert Murray, that “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision” (L. 142). He goes on to say that he has nevertheless cut out “practically all references to anything like ‘religion,’ to cults or practices, in the imaginary world.” He has done this so that “the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.”

But he did leave some clues. The calendar date he gives for the destruction of the Ring is March 25th, which in “the real world” is the Feast of the Annunciation, the day on which Catholics celebrate the beginning of the Incarnation in Mary’s womb.6 Mary was preserved from sin, and strengthened in her will to good, by the grace that flowed into the world (both backwards and forwards in time) from the Cross. Her Yes to the Holy Spirit was therefore the beginning of the final reply to Sauron, and the definitive rejection of the Ring. (In fact there is a longstanding tradition that the Crucifixion also took place on March 25th.) And clearly aspects of Christ and his mission are glimpsed at various points in The Lord of the Rings, for example when Aragorn walks the Paths of the Dead and returns to claim his throne, and when Gandalf gives his life to slay the Balrog in Moria and is “sent back” to Middle-earth in resurrected form as Gandalf the White, endowed with new authority. Frodo and Sam’s journey across Mordor and up the side of Mount Doom carrying the Ring is very reminiscent of Christ’s stumbling walk to Calvary carrying his Cross. In these and other ways, one can tell that Tolkien believes in Christ and also believes that the mission of Christ is bound to send out echoes and reflections throughout human history and mythology.

But these references to Christianity are buried very deep, and one does not have to notice them in order to enjoy the book for its own sake (it is, after all, set in a pre-Christian time). What is more important, and more obvious, is the moral universe that Tolkien portrays, a world of virtues, vices, and temptations. The vices are vividly portrayed in the Orcs and Saruman – greed, envy, pride, hatred, and so on – and in the case of Denethor, the Steward of Gondor, despair. Against these vices he sets the virtues of courage and courtesy, kindness and humility, generosity and wisdom, in the hearts of the Fellowship. And he shows how the human heart is often balanced between the two, as in the case of Boromir or Frodo, where the Ring serves to represent the ultimate temptation, the temptation to wield power over others.

The “Spark of Fire”

I hope I have said enough to suggest some of the ways in which Tolkien can be called anti-modern. He was in many ways a part of the great Romantic movement in European literature. The Romantic poet William Blake also composed great mythological epics, as well as poetry, and criticized the scientific and industrial revolution for its dehumanizing effects on society. The Romantics believed less in Reason and Science than in Feeling and Imagination. Tolkien retained this belief in the importance of the Imagination, but unlike some of the Romantics he also believed in objective Truth, and as a Catholic he tried to integrate emotion and imagination together with rational thought into one comprehensive vision of reality.

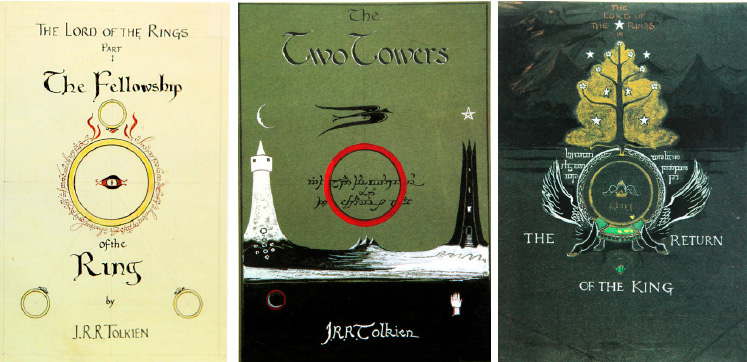

«He felt that the four members of the TCBS, with their refined sense of honor and poetry and beauty, “had been granted some spark of fire… that was destined to kindle a new light, or, what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world”.» Cover designs for the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings by Tolkien.

«He felt that the four members of the TCBS, with their refined sense of honor and poetry and beauty, “had been granted some spark of fire… that was destined to kindle a new light, or, what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world”.» Cover designs for the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings by Tolkien.

But this very fact makes him as much post-modern as anti-modern – or rather, if the term postmodern is associated with the last gasp of modernism and the “failure” of the Enlightenment, we might call people like Tolkien post-postmodern, because they are looking backwards in order to move forwards. As a schoolboy at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, Tolkien formed a close friendship with three other boys who together called themselves the TCBS (Tea Club and Barrovian Society). After they left school and went on to Oxford and Cambridge, and then into the Army to fight in the War, they remained friends. It was through them on the eve of the War that Tolkien found in 1914 his sense of his vocation as a writer. He believed that the TCBS “was destined to testify to God and Truth in a more direct way even than by laying down its several lives in this war” – in a work that may be done “by three or two or one survivor,” always inspired in part by the others. Tolkien, of course, was one of the survivors.

He felt that the four members of the TCBS, with their refined sense of honor and poetry and beauty, “had been granted some spark of fire… that was destined to kindle a new light, or, what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world” (L. 5). Do you see what I mean? The “old light” that they wanted to bring back into the world is the light of beauty and of truth grasped by the Romantic imagination, a beauty of poetry and art and a love of nature that was fast being eliminated by consumerism and mass media, by the noise and pollution and technology that is spreading everywhere. But this is the same as a “new light,” because in a very real sense it is timeless, and by perceiving it we begin to create a new civilization based on a different set of values.

I believe, and I think Tolkien secretly believed, that by writing his stories he had constructed a literary vehicle in which to transmit the vision of the TCBS to the wider world. He had given millions a glimpse of the “old light” of beauty and truth, and for those who allow this light to get into their souls, nothing is ever quite the same again.