To appreciate Newman’s Idea of a University, it is necessary to discuss his rhetorical maneuvers and intentions.

- Robert J. Porwoll

The drama of interpreting meaning

Once an actor takes the stage, he is forced to recite his lines. The audience is watching him, and though our leading man may understand more or less the character he represents and may even take a last glance at the script, once the curtain goes up it is time for him to play his role.

Calderón de la Barca understood human existence pre-cisely from the standpoint of this dramatic dimension: man is forced to act, even though he still does not understand well the meaning of what he does, or the one for whom he does it. In the Great Theatre of the World the spectator is the Lord God himself, who sees the way in which each character represents a virtue or vice without yet understanding exactly what he is doing. Similarly, each man also finds himself on the stage of life having to interpret a character, i.e., himself, about whom he still does not understand many things.

The greatest challenge, however, is that the one on stage has no script. In the great theatre of life, where we find such different characters in such varying circumstances, there is no script, and it seems that everything has to be made up. Nothing is written down, and so everything has yet to be written. Freedom has neither decided nor given its response, and one continually finds oneself standing before a new beginning.1 What shall he say, then? The actor, i.e. each man, will have to play his own role by interacting with his stage companions in the drama of the world. Every man is an actor who interprets a drama, but he is also the drama’s author, becoming in a certain way his own father, creating himself anew as he wills by his own free decisions.2

«We have modern man, who has no idea who man is, in what his perfection consists, and who reduces everything to a radical choice of his own will, whose sole justification is tied to his experience. We find ourselves standing before a man fragmented in a thousand pieces; a thousand different affective moments incapable of offering any sort of intrinsic unity.»

«We have modern man, who has no idea who man is, in what his perfection consists, and who reduces everything to a radical choice of his own will, whose sole justification is tied to his experience. We find ourselves standing before a man fragmented in a thousand pieces; a thousand different affective moments incapable of offering any sort of intrinsic unity.»

Now, if life is ours to fashion, and if neither script nor even a sketch is provided for us pointing out the way to proceed, how are we to accomplish anything beautiful or great in life? Does not affirming the absence of a script imply that everything is merely a grand enigma? And does not this enigma of life give rise to the specter of a great failure?

If it is true that God has not written a script for any man’s life, it is likewise true that he has not left any man alone on the stage, at the mercy of life’s waves which may crash against the shore more or less vehemently in any given situation.

The phrase the meaning of life is meant to bring man’s destiny into focus. When we use the expression “the meaning of life,” what we want to consider is what makes life true and good.3 We are not dealing here with just any truth, but with that specific truth about one’s life that makes it full and complete. Nor are we referring to a fullness that results from a chance success of greater or lesser importance, as often happens in the world of business. The river of life can never be filled with this sort of success, for while such success may be manifold, it is never enough to constitute a successful life taken as a whole.4 Moreover, it should not be forgotten that one might experience a unique fullness even amid failure, as did the Lord himself in his great failure on the Cross. Man, in fact, cannot attain life’s ultimate fullness on his own, for it is offered to him as a gift. Long ago, Aristotle affirmed that happiness was the greatest gift the gods could grant to men.

Questioning the meaning of life therefore involves asking oneself what makes life full and happy, beyond the successes or failures that may occur, and which often do occur without any intervention on our part. Questioning what makes life full and happy, in turn, involves asking oneself what fills one’s actions and activities.5 Happiness is not the simple consequence of acting in order to satisfy one’s expectations and desires, but rather the very fullness that acting itself entails.

In his book Anarchy, State and Utopia (published in the 1960’s), Robert Nozik showed the absurdity of this way of thinking, by appealing to the example of the experience machine.6 He pinpointed the way to show that happiness is something more than satisfaction by imagining a machine capable of satisfying every desire: anyone could plug in, but once you were plugged in, you could not get un-plugged. Who would want to plug into this sort of machine? And would not the fact of wanting to plug into this sort of apparatus be immoral? Why? Well, precisely because whoever plugs in would lose his sense of reality. What we desire, then, is not the mere satisfaction of our desires, but rather the reality of a life full of love, of relationships and of influence on others.

What is it, then, that makes life full? Whence does the meaning that explains the telos, the perfection of a destiny, arise?

The understanding of the telos of each man’s destiny cannot be gained simply through a study of nature. It is true that man’s rational nature points to a telos common to all men, inasmuch as there would be no human perfection unless it included understanding and freedom, dimensions specific to the human animal. It is only in knowledge and freedom that man may become the protagonist of his own destiny. But this is still too generic, and every person is unique and unrepeatable. What appears to be good for all may not appear so to the individual. What one society proposes as good and noble may not be so for another. And what parents propose as good to their children may not be seen as good by them.

The meaning of life, i.e., what fills it with life and goodness, has to be discovered by each man. And this can only happen if a person accepts that he must interpret everything that happens to him. For the meaning of life is unveiled precisely in the events that form it.

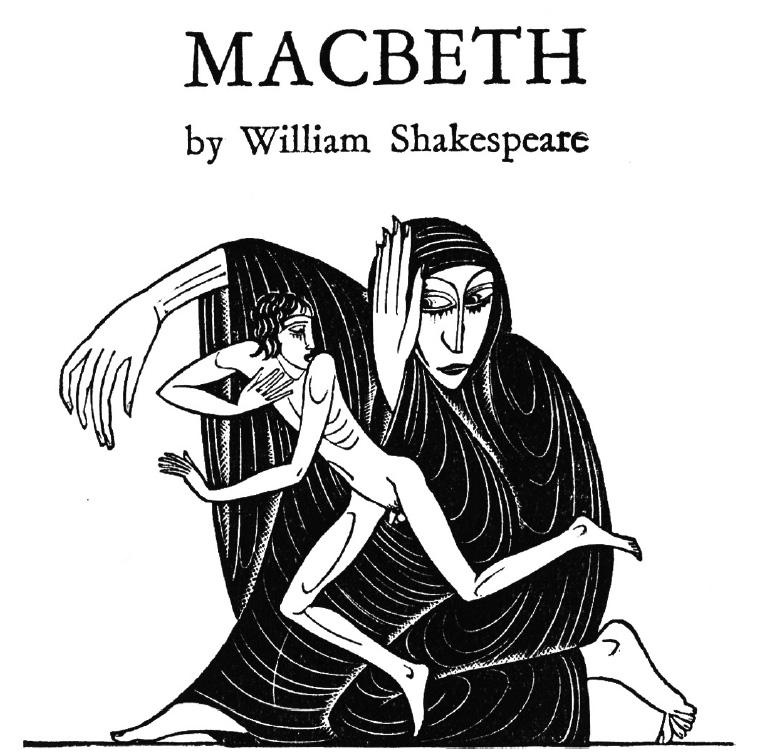

As Macbeth makes his way with Banquo on their journey to Forres, he is startled by three witches who greet him with a most surprising message: “All hail, Macbeth, that shalt be king hereafter!”7 Macbeth, together with his friend, wonders about the meaning of this prophecy. However, it is only when he arrives home and speaks with his wife that he understands it and recognizes himself in the message. His wife, who is seized by ambition, will eventually convince Macbeth to act against the king in order that the prophecy might be fulfilled. And here is Macbeth’s mistake: rather than waiting for destiny progressively to unfold, he forces reality to fit the divination.

«Alasdair MacIntyre has shown how modern reflection has led to an emotivist conception of man that reduces the person to the “emotivist self.” Who is this man? He is an individual who is incapable of providing any reasons for his conduct, since he has lost any sense of the meaning of the fullness and completion of the human person and of his actions.»Shakespeare did not believe in witches, but his recourse to this image offers him the necessary literary device for opening his protagonist’s horizon. The witches indicate the world of magic, or something beyond rational control. There is something magical about understanding destiny, something that goes beyond reason, since it allows one to understand life as a whole. Thus, the great English writer places his character before a destiny and observes his reactions: this explains the astonishment when, by the instigation of the wickedness of his wife, Macbeth gives way to wild ambition and everything begins to depend on his ideas and abilities. He willed that his destiny be solely the work of his own hands, of his own labor. This, however, reduces destiny to human measure. It is clear from this experiment that he to whom destiny is announced, if he forces it, sets himself on an evil path and becomes a despot king.8

«Alasdair MacIntyre has shown how modern reflection has led to an emotivist conception of man that reduces the person to the “emotivist self.” Who is this man? He is an individual who is incapable of providing any reasons for his conduct, since he has lost any sense of the meaning of the fullness and completion of the human person and of his actions.»Shakespeare did not believe in witches, but his recourse to this image offers him the necessary literary device for opening his protagonist’s horizon. The witches indicate the world of magic, or something beyond rational control. There is something magical about understanding destiny, something that goes beyond reason, since it allows one to understand life as a whole. Thus, the great English writer places his character before a destiny and observes his reactions: this explains the astonishment when, by the instigation of the wickedness of his wife, Macbeth gives way to wild ambition and everything begins to depend on his ideas and abilities. He willed that his destiny be solely the work of his own hands, of his own labor. This, however, reduces destiny to human measure. It is clear from this experiment that he to whom destiny is announced, if he forces it, sets himself on an evil path and becomes a despot king.8

Does such an explanation end up being too distant from the modern world of technology and science? Witches are not an object of belief today either, but we do have to admit that, as in the age of Macbeth, we sometimes experience moments when the future opens up before us and presents itself as something fascinating and attractive. What are these moments? They are the rich experiences that involve the affections. These moments are full of promise, but their meaning and fulfillment are not immediately apparent.9

These moments are ones of truly loving emotion, when a new fullness opens up before us that cannot be attained on our own, but rather only in the joyous company which is given to us, and which allows us to live in harmony. They also occur at those times when fear oppresses man and brings him to experience the magnitude of his destiny and the depth of his own frailty. And they include the occasions when we come to understand the gift that someone makes to the deepest part of man by his presence, creating intimacy and filling the heart with joy; or even the moments when anger takes hold of the heart, when we see the evil of someone who is threatening those whom we love. Such love, such fear, such joy and such anger, together with so many other affections – hope or desperation, desire or distress – are not mere states of mind, emotions without precise intentionality, or sentiments devoid of meaning.

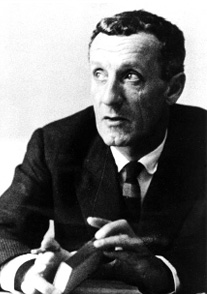

Alasdair MacIntyre10 has shown how modern reflection has led to an emotivist conception of man that reduces the person to the “emotivist self.” Who is this man? He is an individual who is incapable of providing any reasons for his conduct, since he has lost any sense of the meaning of the fullness and completion of the human person and of his actions. The Scottish philosopher offers a fitting analogy, which compares modern man to a castaway who finds himself shipwrecked on a deserted island. He sees pieces of the vessel that transported him make landfall on his island, but what good are these pieces without the idea of the ship, i.e. if he has never seen the ship as a whole? Any attempt to reconstruct the vessel would be impossible under such circumstances.

Here, then, we have modern man, who has no idea who man is, in what his perfection consists, and who reduces everything to a radical choice of his own will, whose sole justification is tied to his experience. We find ourselves standing before a man fragmented in a thousand pieces; i.e., a thousand different affective moments incapable of offering any sort of intrinsic unity.

But is this truly all that feelings are: fragmented moments of life, devoid of any meaning?

They are, in fact, the exact opposite. For something decisive about man is revealed in the affections, which are experienced in the feelings and emotions. They, like the witches of the Shakespearean tragedy, have a decisive hermeneutic value in that they help man to understand himself, the meaning of his life, and what a true and good life really is, a life that is worthy of being sought; or on the contrary, what ruins life and makes it lose momentum. The affections are like “upheavals of thought,” to draw upon the beautiful image of the well-known American philosopher Martha Nussbaum.11 They permit us to go beyond ordinary everyday life and to look out upon the horizon. The destiny of every man is disclosed in his affections.

Stating this, however, implies the need to know how to interpret these affections.12 We may, of course, distinguish “true” sentiments from those which are “false,” and we may certainly recognize  «We may, of course, distinguish “true” sentiments from those which are “false,” and we may certainly recognize that not everything that we feel inside stands on the same plane of existence, and that not everything is true in the same way. We know that within us there are varying degrees of reality, just as outside of us there are “reflections,” “phantasms,” and “things.” Along with true love there is also a false or illusory love, as the great philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty stated.»that not everything that we feel inside stands on the same plane of existence, and that not everything is true in the same way. We know that within us there are varying degrees of reality, just as outside of us there are “reflections,” “phantasms,” and “things.” Along with true love there is also a false or illusory love, as the great philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty stated.13

«We may, of course, distinguish “true” sentiments from those which are “false,” and we may certainly recognize that not everything that we feel inside stands on the same plane of existence, and that not everything is true in the same way. We know that within us there are varying degrees of reality, just as outside of us there are “reflections,” “phantasms,” and “things.” Along with true love there is also a false or illusory love, as the great philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty stated.»that not everything that we feel inside stands on the same plane of existence, and that not everything is true in the same way. We know that within us there are varying degrees of reality, just as outside of us there are “reflections,” “phantasms,” and “things.” Along with true love there is also a false or illusory love, as the great philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty stated.13

Interpreting the affections therefore means searching for the truth they conceal, which is not merely the existence of the feeling itself. The truth of affection is not like sincerity; it does not answer the equation: I feel, therefore it is. The spontaneity with which the affections arise may conceal their intentional significance and enclose man within his own emotional intensity. The truth of feelings is revealed when the feeling is placed in relation to the whole of life.14

Interpretation therefore entails looking for the teleology of feeling: seeing where it leads, and how it makes the fullness of life more or less possible.

In order to interpret them rightly, we must first understand that feelings have a teleology, that they are not meant to end in their own inner intensity. And to understand this, a youngster first has to know how to identify this dimension in others.

Feelings arise as the fruit of events that happen in life. Man experiences love because a woman strikes him by her personality and beauty; he experiences sadness when the one he loves slips out of his hands; and he experiences anger when someone threatens him.

These are events that have an impact on his subjectivity: reality strikes him and transforms him. But what exactly is this reality? Principally, it is one that is woven out of interpersonal relationships. It is others who affect man and introduce changes in him, knitting together his still vulnerable and delicate inner life.15

Affections, then, are something that happen within man but without him being able to decide on their being there: affections often arise without him being able to plan for them, avoid them or produce them. In this sense, they have something in common with magic, for they cannot simply be deduced by, or reduced to, reason. Their magic resides in their unpredictability. Yet when they do occur, then it is that a man is able to understand their reasonableness, for they have an inherent logos that goes well beyond their being experienced.

At first a person understands this mechanism, not by experiencing it firsthand, but by looking at the stories of others. In the stories we hear as children, we begin to learn that the affections do not end once they are felt, since they generate situations that continue to play out in the story. The child does not yet have a sense of the duration of time or of the continuity of the person: for him everything seems to be spent in the intensity of what he feels; he is continually experiencing new and different things that have but one point of continuity: himself. The intensity with which fear or jealousy, love, hatred or anger present themselves seems to fill and determine the entire space, requiring his complete and immediate adherence.

The child is accustomed to hearing stories from his parents about animals, ancient heroes, or family and friends with whom he may identify. Though still young, he is able to understand how the fear that the soldier felt, and which led him to betray his nation, caused a true disaster for so many; or how Ulysses’ daring to push the limits and go beyond the Pillars of Hercules led to the sinking of his ship and to the death of all his companions. Or again, how Dante’s trust in his beloved moved him to allow himself to be guided along the most beautiful adventure toward heaven ever told, or how the courage of the lion king who, having conquered his fear and his desire to flee, brought peace to his land.

These are stories that, by recounting the lives of others, manifestly show that the affections do not end in themselves, in that particular moment of anger or fear or love;

but rather, that they lead to something that generates a new situation. And it is that something which may determine the preciousness of the affections, or the lack thereof, according to the circumstances. The affections therefore have an intrinsic rationality, which points not only to mere satisfaction, but also to a fullness of the individual with respect to other persons. In dealing with fear, sadness, love, bravery, anger, the need for a response arises that opens to a life more or less true, not only for the individual but also for all those around him. This is how the affections cause a common good to emerge in which each of the different attractions acquires meaning.

One of the great problems of modern storytelling is that, rather than allowing us to glimpse the whole, it only shows us a part, albeit with great intensity. In other words, today all the effort is focused on producing empathy in the spectator, in making him experience what the protagonist experiences, but without any reference to the meaning of this feeling,16 i.e. without reference to what makes the fullness of life more or less possible. However, reducing affections to feelings involves a great impoverishment, precisely because the affections do not appear clearly to reason: they remain largely hidden. With feeling, the important thing is what is experienced; it is the possibility of acting on the basis of what one experiences, unaware of the future and of what the balance in human relationships will be, which matters most. Today the stories presented by the mass media only show a fragment of the story. To a great degree, they involve the viewer affectively, but they obfuscate the possibility of his opening himself to the totality of what the affection contains.

«Macbeth gives way to wild ambition and everything begins to depend on his ideas and abilities. He willed that his destiny be solely the work of his own hands, of his own labor. This, however, reduces destiny to human measure. It is clear from this experiment that he to whom destiny is announced, if he forces it, sets himself on an evil path and becomes a despot king.»

«Macbeth gives way to wild ambition and everything begins to depend on his ideas and abilities. He willed that his destiny be solely the work of his own hands, of his own labor. This, however, reduces destiny to human measure. It is clear from this experiment that he to whom destiny is announced, if he forces it, sets himself on an evil path and becomes a despot king.»

Our purpose here is not to advocate uplifting stories that show us by their happy ending how to resolve difficult situations. What we are attempting to show is that, in order to interpret the affections rightly, we need to allow them to reveal their inherent intentionality rather than hiding the drama they bear. The problem is not that the media portrays violence and eroticism, but rather that they do so in a way that does not allow a person to understand their link, or lack thereof, to man’s destiny. It is only by making this horizon his own that a man will be able to understand whether an affection fragments his life, or instead provides him with a new principle of integration, as he pursues the beautiful thing that has been promised to him in the event of the encounter.

Stories, on the other hand, help us to see the affections in context, whether fear, love, hatred envy, jealously, daring, etc., by allowing the whole story to unfold, and by locating the origin of the affection in behavior that succeeds, more or less, in bringing fullness to life. Indeed, this fullness is already present at source of the affection and determines its own truth as well as the identity of the subject.17

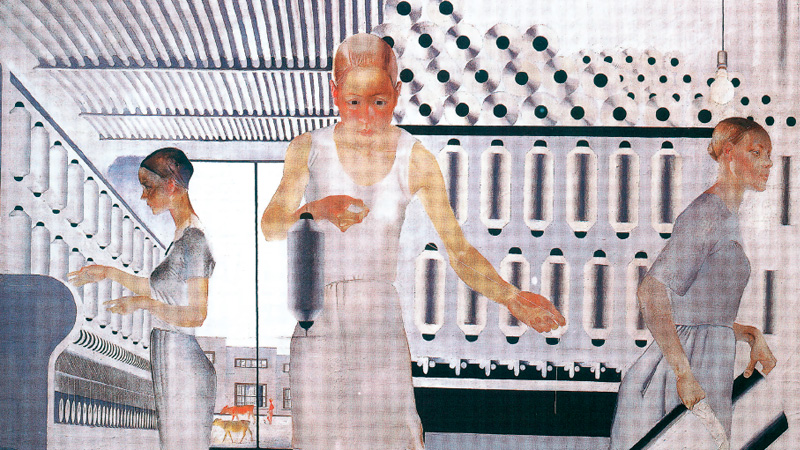

In classical Greece, the adventure of the paideia, i.e., the education of the generations, was carried out precisely by recounting mythological tales and by the tragedies of the theater.18 With these as their instruments, the Greeks succeeded in portraying a whole universe of meaning and in

showing the relationship between a concrete moment and a person’s global destiny.

The outcome of Shakespearean theatre is also to be understood in this light. Certainly these dramas have the particular power or bringing a passion to life on stage, but beyond this their great merit lies in their power to reveal the passion’s anthropological value, i.e. its capacity to render life truly full. Revenge is not what guides the whole of Hamlet. Rather, it is Hamlet’s dilemma over the meaning of a life in which he finds himself having to accept that his own father was murdered by his uncle, in connivance with his own mother, and that now, the very same uncle married her. The drama of revenge is the very need for justice. Hamlet will only be able live a full life by enacting justice; otherwise, his life is ruined and gone mad. His “to be or not to be” refers to an essential question of life, to what makes life human: one cannot live in the kind of relationship in which Hamlet finds himself.

The stories a person hears throughout his life allow him, then, to get a first, external glimpse into the meaning of the great passions of life. They also provide him with an opportunity to identify himself to a greater or lesser degree with their heroes and characters. The first step is for him to understand that the affections do not end in themselves, and that because of this, he will need to know how to interpret them by distancing himself from the affective intensity which accompanies them.

The second step is to understand that the affection one experiences is a real provocation and challenge to one’s freedom. Indeed, every man is Ulysses or Laocoön, Antigone or Macbeth, Romeo or Don Quixote. Every man is called to respond to the desire for adventure, to the anger, to the

injustice, to the ambition, to the love, to the ideal that he finds in his life. Not to respond is already a response. Every man is an actor on life’s stage, and whether he likes it or not, he is playing a role.

A man’s freedom is challenged and provoked by his affections. However, for freedom to respond appropriately, it has to understand the meaning of the affection; that is, the relationship between the affection and his fulfillment as a human person.

And here we come to the point: a man will never understand this relationship if his free will does not wish to be engaged. What comes first, then, meaning or freedom? If it is true that the meaning of an event challenges and provokes our freedom, it is equally true that one who is unwilling to act cannot understand. To solve the mystery, we need to introduce a new element that explains the ultimate root of human freedom.

What moves our freedom to become involved in this process? Freedom will only make this step if it receives love, if it understands the love that is at play. It is love that awakens freedom, that embraces it and that renews it from within. Therefore, there is a hermeneutic circularity between the event, freedom, meaning and love. Love is the new element that allows us to understand freedom’s dynamism. The stories we listen to can certainly help, but in order truly to understand, we need to be able to perceive the love that is at play; i.e., the love that touches the heart of man and calls him to something beautiful and great.

Within this context, praxis emerges as a qualifying element of truth: not because praxis produces truth,19 but because we are dealing with the truth that touches life in its inner core and which man can understand only if he sets out on the journey.

The first act, then, consists in trusting in the love that is offered, and in the value of the story that is handed on.20

For light to be shed on the meaning of life – on the destiny that makes it so beautiful and great – and for man to desire it and take his proper place therein, he needs continual contact, life lived together, and conversation. Plato explains it in this way: “but after much converse about the matter itself and a life lived together, suddenly a light, as it were, is kindled in one soul by a flame that leaps to it from another, and thereafter sustains itself.”21

The importance of a child’s surroundings (and their centrality in helping him grasp the meaning of life) now begins to emerge. These surroundings consist in a collection of irrevocable relationships that cannot be modified without the persons involved changing as well. Intergenerational relations, fatherhood and motherhood, childhood, fraternal bonds, and the relationship between spouses: these are the relationships that allow family members to offer one another irrevocable love based not on the pleasure of the moment or on the satisfaction that the other offers, but on a sharing of life’s fullness, on the communion of persons. This is the context in which a child or youngster is also vulnerable to a whole set of interpersonal relationships that affect and challenge him.

However, because these relationships are based on irrevocable love, they allow the meaning of the affections they generate through daily encounters and skirmishes to emerge.22 The child is called through these events to take responsibility for his own actions and to interpret his own role. He cannot hide behind the fact that he does not understand the meaning of what is happening, because everyone around is continually reminding him of similar stories, and is asking for his own free response, so that the fullness of family life may be theirs. It becomes immediately apparent in family life that the affections do not end in themselves, and that, if it is important to feel them – indeed, if it is beautiful feel them – still everything is not confined to feeling. For in order for family life to go on, all of its members need to act and to build, and not only to feel.

«The great teacher in values, Max Scheler, said of himself as he reflected on his own inner difficulties and the ruin they caused in his life: “I will never forgive God for having made a beast like me.” Communicating meaning therefore means offering a space and a place in a true relationship.»

«The great teacher in values, Max Scheler, said of himself as he reflected on his own inner difficulties and the ruin they caused in his life: “I will never forgive God for having made a beast like me.” Communicating meaning therefore means offering a space and a place in a true relationship.»

Within this context, the child comes to understand that his actions always appear as reactions to the actions of the others. In this way, he begins to conceive of a “family ‘we,’” the common representation everyone offers together, and in which each member has his own specific role to play. The child begins to experience the joy of interacting, according to his own role, in the “family ‘we.’” In accepting this challenge, which brings him out of his own interests and desires, the child – who until then was enclosed within “his good” and identified it with what he liked – begins truly to understand what the true good is, i.e. the common good, the good of a family communion made possible by all its members. From this perspective, we can see how man does not truly know how to say “my good” until he is able to say “our good.”23

Therefore, the role of stories is decisive in so far as they provide a first hint at the meaning of the affections. They thereby direct the affective energy from the outset towards the more excellent ways of experiencing affection, ways capable of fulfilling life, of rendering it full and true, ways worthy of imitation.24 The love a child receives will enable

him to open himself to trust and to act for the sake of the common good, by shaping his desires as never before, so that these very desires stably direct him toward the excellence of behavior that truly fulfills life.

The teleology of love, and the stories that are handed down from one generation to another, allow the meaning of the affective event to emerge.

Education (and the communication of meaning it involves) is not simply a matter of passing on information about values. Educating in values is important, but it has its limits: for it is one thing to learn to appreciate a symphony and quite another to play the violin. The great teacher in values, Max Scheler, said of himself as he reflected on his own inner difficulties and the ruin they caused in his life: “I will never forgive God for having made a beast like me.” Communicating meaning therefore means offering a space and a place in a true relationship.

Education involves a true drama: a drama of reciprocal interaction between individuals in a community of action, which is sustained and guided initially by educators, and whose sole aim is to enkindle a light in the one who is being educated so that he, too, might find his proper place. And this is where assistance in interpreting the affections may come in; these affections have a direct relation to a life full of successful relationships; therefore, they need to be molded and shaped to move in that direction. Macbeth was a victim of an illusion. He himself recognizes this at the end, when he sees the woods surrounding Dunsinane advance toward the castle: “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

But are things really this way? Dear Macbeth, you did not interpret well the witches’ saying and, seized by your own ambition, you thought that you had to realize your own destiny. However, destiny is not fulfilled only through the work of one’s hands. And, above all, one’s destiny is never realized by bloodying one’s hands. You lacked a context of true love to interpret well the witches’ words. You perceived as an echo the voice of your wife, who like you was drunk with ambition. You lacked an authentic communion of persons that would have allowed the meaning of something beautiful to emerge.

We can neither understand nor mold meaning by ourselves. It emerges through events, but only within a context of communion, and only if we are provoked and challenged to interact for the sake of the common good. On the stage of life, we will understand what role we are to play if the persons with whom we interpret the drama live out the grandeur and greatness of their relationships in true communion. For it is here that the horizon of fullness that gives meaning to our representation of life emerges.

Translated by Diane Montagna

Let me get up front to the central claim of my article1: What is increasingly missing from the late-modern research university and the kind of training it offers is what I shall call the university’s third dimension. For the American Association of Universities (AAU) this third dimension seems to have disappeared from the university. The first two dimensions of the late modern university constitute its “sharpness” as problem-solving institution: to intricate questions and to solve complex problems. The late modern university accomplishes this task by way of ever more specialized research and by way of a concomitant training of undergraduate and graduate students in the kind of expert knowledge that makes them competent problem-solvers. The university’s third dimension—constitutive of the classical university—comprises, first, scholē (in English “leisure”) that is, the structured practice of intellectual contemplation and reflection, and, second, paideia, that is, the integral formation of the intellectual virtues in conjunction with the development of the moral virtues. A university that lacks this third dimension might well be able to develop remarkable research, but, I think, will eventually suffer from a suffocating intellectual spiritual flatness that in the long run will prove detrimental to the university as such. In order to make good on this claim I will proceed through three steps. In the first step, I will offer a snapshot of the late-modern research university and highlight three of its noteworthy features: first, the remarkable ambivalence in contemporary academic thought pertaining to reason’s reliability and range, and, ultimately, to reason’s capacity for truth; second, the late-modern university’s pervasive embrace of the means of quantification or metrics for purposes of assessment and management (into which university administration seems to have largely morphed); and third, its embrace of the allegedly neutral framework of "secular reason" for its internal and external communication. These features belong essentially to what I regard as the university’s first and second dimension that together constitute the cutting edge, the utilitarian character of a highly complex problem-solving machine. The university’s third dimension, its depth dimension, refers to what has been at one time essential to the university qua university, that is, the pursuit of larger, comprehensive and integrating questions of truth and meaning—questions, I dare say, of metaphysics and morals. What is to be observed at the present moment regarding this third dimension are signs of a new emerging disenchantment with secular reason as the university’s governing principle, a disenchantment discernible as it seems first and foremost among some of the postmodern avant-gardes of the late-modern research university. ”

In a second step, I shall consider a brief philosophical observation and an equally brief theological reminder about the university’s third dimension.

In a concluding third step I will conclude that leisure and paideia are the two practices that keep the soul of the university alive and that will assure that the university qua university will continue to matter even under the specter of a comprehensive functionalization of the late-modern university—especially after the disenchantment of secular reason.

Like all thought, the normative perspectives that inform my critique of the late-modern research university and the concomitant university education come from somewhere. The perspective that informs the normative understanding of the university pursued here has its roots in the ancient paideia that came to flourish in the remarkable and still pertinent work of Thomas Aquinas. Obviously, this idea of university does not form the matrix on which the late-modern universities are built. However, I still hold as a governing principle for the subsequent reflections that a vision like the following is required as a critical normative standard in order to help us see at which point the “university” is in danger of becoming an equivocation (that is, a branding fraud). To quote Alasdair Mac- Intyre from his recent God, Philosophy, Universities: A Selective of the Catholic Philosophical Tradition: “The ends of education… can be correctly developed only with reference to the final end of human beings and the ordering of the curriculum has to be an ordering to that final end. We are able to understand what the university should be, only if we understand what the university is. But while this thought was crucial for Aquinas’s conception of the university, it was remarkable uninfluential in determining how universities in fact developed.”2

«Newman is right: liberal education is meant not for the cultivation of the saint, but for the cultivation of the intellect; the university is meant for the excellence that characterizes the saint. The gentleman Newman invokes should, I think, be understood as an intellectually well-formed socially competent person. But here I think Newman is granting a point tacitly that at other instances in his work he was willing to support explicitly: that paideia, the formation of character, is integral to a university education. For, arguably, the formation of intellectual virtues occurs best in conjunction with the formation of character.»

«Newman is right: liberal education is meant not for the cultivation of the saint, but for the cultivation of the intellect; the university is meant for the excellence that characterizes the saint. The gentleman Newman invokes should, I think, be understood as an intellectually well-formed socially competent person. But here I think Newman is granting a point tacitly that at other instances in his work he was willing to support explicitly: that paideia, the formation of character, is integral to a university education. For, arguably, the formation of intellectual virtues occurs best in conjunction with the formation of character.»

Describing and understanding the de facto development of universities in historical, sociological, and political terms is one kind of thing. Making sense of the university qua university on intellectual terms is another thing. I am pursuing only the latter here, and the presupposition of my talk is that the ideal reflected in Aquinas’s thought, and echoed to some degree under considerable different conditions in John Henry Newman’s 1852 Dublin lectures on The Scope and Nature of University Education, is far from obsolete. On the contrary, this ideal constitutes the corrective reminder and salutary challenge and is as such a program, I submit, superior to the Enlightenment model of the university as a place of advanced training in useful competencies, superior well to the Berlin-type and the Weberian version of the late-modern research university. For all these later models share the deficiencies of modernity; that is, they regard the university’s third dimension as dispensable and, if maintained, as at best a supererogatory concession to a luxury admitted for purely sentimental reasons, namely as one expedient way to honor the university’s pre-modern roots.

«For late modernity, that is, a thoroughly secularized and increasingly fragmented modernity, has now lost its optimistic élan and instead has become tired and cynical. In the agnostic world of irresistibly corruptible, interminably quarrelling, and tirelessly consuming bodies, hence a world in which the greatest dangers are disease, litigation, and the inability to consume, the hierarchy of university sciences stands in service of the avoidance of these evils: at the top stands the medical school supported by all the biomedical sciences, followed by the law school and the business school supported by their respective auxiliary sciences, first and foremost computer science and mathematics, but also any useful remnants of the liberal arts.»

Let me expand upon what I mean by the third dimension. In 2006, as an octogenarian, the philosopher Benedict Ashley published a simply remarkable book, a model of interdisciplinary rigor and comprehensiveness, The Way toward Wisdom: An Interdisciplinary and Intercultural Introduction to Metaphysics. Let me use his words to amplify this idea of the university’s third, integrative dimension.

The very term “university” means many-looking-toward-one, and is related to the term “universe,” the whole of reality. Thus, the name no longer seems appropriate to such a fragmented modern institution whose unity is provided only by a financial administration and perhaps a sports team. The fragmented academy is, of course, the result of the energetic exploration of all kinds of knowledge, but how can it meet the fundamental yearning for wisdom on which each culture is based?3

The search for wisdom characterizes the university’s third dimension and realizes the university qua university in a strict and proper sense. Hence, the university’s third dimension functions as critical norm that puts into stark relief strong tendencies—not recent in the origin, but recently gaining remarkable momentum—to reduce the university to a polytechnicum with a largely functionalized propaedeutic liberal arts appendix, this polytechnicum being largely an accidental agglomeration of advanced research competencies gathered in one facility for the sake of extrinsic and contingent convenience. If this trend should come to its logical term, if indeed each of these ad-vanced research competencies could be located elsewhere, that is, be directly linked to hospitals, to biochemical and computers companies, or to this or that branch of the military-industrial complex, without any lost, then the university in any substantive sense would have disappeared; and to still call what remains a university would be simply an equivocation, undoubtedly useful for reasons of branding and marketing, but hardly for reasons of substance.

1. It is hard to imagine a gulf deeper than the one that currently exists between those academics who regard reason in terms of utmost triumph and those who regard it in terms of utmost despair. Mathematically disciplined and technologically executed, human reason has transformed the globe in unprecedented ways. The academic disciplines based on reason’s mathematical and technological acumen hold a robust trust—if not faith—in reason’s capacity to grasp reality and, precisely because of this grasp, successfully to conform the world to human interest and needs.

Paradoxically, we can register a simultaneous widespread sense of despair about reason’s superior status and role. Instead of sovereignly guiding human affairs to their clear, defined, and well-considered ends, reason seems to be a little more than a coping mechanism or a regulative fiction driven and directed by instincts and desires it can hardly perceive, much less rule. The academic disciplines that traditionally draw upon reason’s reflective, integrative, and directive capacities— and exercised by humanity in the act of understanding and interpreting both world and self—seem to have fallen into a state of internal disarray while finding themselves exiled into what by all accounts seems to be a state of permanent marginalization within the late-modern research university. Reason triumphing in the form of instrumental rationality has produced its own demise as famously analyzed in Max Horkheimer and Theodore Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment.

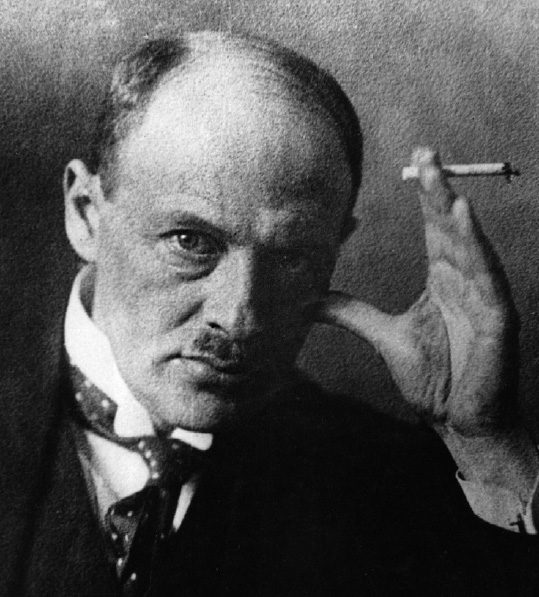

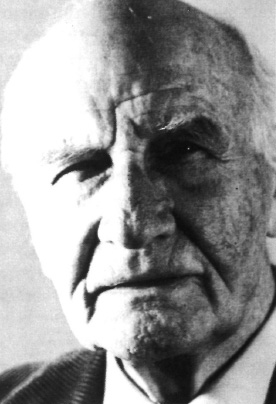

«Instrumental rationality and ontological nihilism seem to be two sides of the same coin. What is eclipsed in between is this question of truth. Because reason seems to have become incapable of attaining truth, it has to assert itself instead in the gigantomaniac demonstration and celebration of its instrumental effectiveness, its will to power. The prophet of this dynamic has been Friedrich Nietzsche. While Nietzsche was greatly disillusioned with the nineteenth century Berlin-style university, the late-modern, secular research university with its strong pragmatic and anti-metaphysical bent is more profoundly committed to some Nietzschean tenets that it seems to be aware.» Edward Hooper, Night Shadow, 1921.

«Instrumental rationality and ontological nihilism seem to be two sides of the same coin. What is eclipsed in between is this question of truth. Because reason seems to have become incapable of attaining truth, it has to assert itself instead in the gigantomaniac demonstration and celebration of its instrumental effectiveness, its will to power. The prophet of this dynamic has been Friedrich Nietzsche. While Nietzsche was greatly disillusioned with the nineteenth century Berlin-style university, the late-modern, secular research university with its strong pragmatic and anti-metaphysical bent is more profoundly committed to some Nietzschean tenets that it seems to be aware.» Edward Hooper, Night Shadow, 1921.

This arguable state of affairs is obviously not just an ivory-tower phenomenon, remote from and largely irrelevant to human society at large. Rather, the simultaneous triumph of and despair about reason mirrors late-modern society as such: we encounter breathtaking developments in artificial intelligence and biotechnology together with atmospheric epistemological skepticism and ontological nihilism that is as pervasive and erosive as it is elusive. Instrumental rationality and ontological nihilism seem to be two sides of the same coin. What is eclipsed in between is this question of truth. Because reason seems to have become incapable of attaining truth, it has to assert itself instead in the gigantomaniac demonstration and celebration of its instrumental effectiveness, its will to power. The prophet of this dynamic has been a German university professor of the nineteenth century, one who retired very early in his career from the university: Friedrich Nietzsche. While Nietzsche was greatly disillusioned with the nineteenth century Berlin-style university, the late-modern, secular research university with its strong pragmatic and anti-metaphysical bent is more profoundly committed to some Nietzschean tenets that it seems to be aware. Let me, for just one example, cite aphorism 480 from The Will to Power:

There exists neither “spirit,” nor reason, nor thinking, nor consciousness, nor soul, nor will, nor truth: all are fictions that are of no use. There is no question of the “subject and the object,” but of a particular species of animal that can prosper only through a certain relative rightness; above all, regularity of its perceptions (so that it can accumulate experience). Knowledge works as a tool of power. Hence it is plain that it increases with every increase of power. The meaning of “knowledge”: here, as in the case of “good” and “beautiful,” the concept is to be regarded in a strict and narrow anthropocentric and biological sense. In order for a particular species to maintain itself and increase its power, its conception of reality must comprehend enough of the calculable and constant for it to base a scheme of behavior on it. The utility of preservation—not some abstract-theoretical need not to be decided—stands as the motive behind the development of the organs of knowledge—they develop in such a way that their observations suffice for our preservation. In other words measure of the desire for knowledge depends upon the measure to which the will to power grows in a species: a species grasps a certain amount of reality in order become master of it in order to press it into service.

What would the kind of university look like in which Nietzsche’s understanding of the human being took hold, at least tacitly, of its self-understanding? This brings me to another segment of snapshot.

2. A university in which Nietzsche’s understanding of human being took hold would be, to say the least, profoundly ambivalent about itself—and remember, the best strategies to cope with ambivalence in matters of substance and teleology is quantification of metrics, instrumentalization, and management. It would also be a place in which philosophy would share an unequivocally marginal position with the other humanities, in which what once were the “liberal arts” would be characterized by curricular fragmentation and even disarray, and a place in which the biotechnological science would display an almost uncontrollable—should I say cancerous? —growth. Such a “university” —I put the  «In the speech for Rome´s La Sapienza University, Benedict pointed to the self-deception of secular reason. “If our culture seeks only to build itself on the basis of the circle of its own argumentation and what convinces it on the time, and if—anxious to preserve its secularism—it detaches itself from its life-giving roots, then it will fall apart and disintegrate.” Like late-modern society, the late-modern research university lives from intellectual and moral sources it cannot account for, let alone produce. The university’s third dimension, however, seems to depend precisely on such intellectual and moral sources.»word into quotation marks—would be first and foremost a highly sophisticated problem-solving machine at the service of those who are able and willing to pay for its service. In different, that is, more positive Benthamian terms: the late-modern research universities as they can be found across the globe are by and large institutions geared first and foremost to producing knowledge by way of highly specialized research (primarily in the natural and medical sciences), knowledge that is meant to serve interests that almost exclusively arise from the practical and technical needs and demand of the kinds of societies in which these universities are located. In a secondary way, these universities are geared to communicate this knowledge in order to produce specific competencies in their graduates. The undergraduate’s education—most lately blatant in Europe’s new Bologna system—is increasingly functionalized toward the acquisition of marketable skills and competencies. Added to these clearly defined, specialized competencies comes to stand an equally well defined set of so-called “Rahmen-Kompetenzen,” framework competencies. For it must be ensured that future Einsteins, Hawkings, Wittgensteins, Habermases and Auerbachs know how to lead effective small groups discussions, can organize laboratory teams, and prepare compelling Power-Point presentations.

«In the speech for Rome´s La Sapienza University, Benedict pointed to the self-deception of secular reason. “If our culture seeks only to build itself on the basis of the circle of its own argumentation and what convinces it on the time, and if—anxious to preserve its secularism—it detaches itself from its life-giving roots, then it will fall apart and disintegrate.” Like late-modern society, the late-modern research university lives from intellectual and moral sources it cannot account for, let alone produce. The university’s third dimension, however, seems to depend precisely on such intellectual and moral sources.»word into quotation marks—would be first and foremost a highly sophisticated problem-solving machine at the service of those who are able and willing to pay for its service. In different, that is, more positive Benthamian terms: the late-modern research universities as they can be found across the globe are by and large institutions geared first and foremost to producing knowledge by way of highly specialized research (primarily in the natural and medical sciences), knowledge that is meant to serve interests that almost exclusively arise from the practical and technical needs and demand of the kinds of societies in which these universities are located. In a secondary way, these universities are geared to communicate this knowledge in order to produce specific competencies in their graduates. The undergraduate’s education—most lately blatant in Europe’s new Bologna system—is increasingly functionalized toward the acquisition of marketable skills and competencies. Added to these clearly defined, specialized competencies comes to stand an equally well defined set of so-called “Rahmen-Kompetenzen,” framework competencies. For it must be ensured that future Einsteins, Hawkings, Wittgensteins, Habermases and Auerbachs know how to lead effective small groups discussions, can organize laboratory teams, and prepare compelling Power-Point presentations.

It was none other than Newman, who in his lectures on The scope and nature of the university—lectures more relevant than ever, I dare say—more than 150 years ago anticipates the specter of the late-modern research university. He discerns its seed in the scientific method of another of its founder fathers—Francis Bacon.

I cannot deny [Bacon] has abundantly achieved what he proposed. His is simply a Method whereby bodily discomforts and temporal wants are to be most effectually removed from the greatest number; and already, before it has shown any signs of exhaustion, the gifts of nature, in their most artificial shapes and luxurious profusion and diversity, from all quarters of the earth, are, it is undeniable, by its means brought even to our doors and we rejoice in them.4

But in the course of 150 years since Newman’s rather friendly characterization of the Baconian university, things have become considerably graver. For late modernity, that is, a thoroughly secularized and increasingly fragmented modernity, has now lost its optimistic élan and instead has become tired and cynical. In the agnostic world of irresistibly corruptible, interminably quarrelling, and tirelessly consuming bodies, hence a world in which the greatest dangers are disease, litigation, and the inability to consume, the hierarchy of university sciences stands in service of the avoidance of these evils: at the top stands the medical school supported by all the biomedical sciences, followed by the law school and the business school supported by their respective auxiliary sciences, first and foremost computer science and mathematics, but also any useful remnants of the liberal arts. And since it has been discovered that allegedly religious practice might contribute health and longevity, the gods are making a come-back, of sorts—now as an appendix to the medical school!

It is in light of these recent developments that the warning of Pope Benedict XVI—himself a long-time university professor profoundly committed to this unique institution of higher learning–—has an especially salient and sobering ring. The following is part of a speech that the Pope prepared in January of 2008 for the Roman university La Sapienza (once the Pope’s own university in Rome, now a secular Roman university), a speech that, however, was never delivered because at the last moment the university administration withdrew the invitation. Here is the pertinent passage, however:

The danger for the western world—to speak only of this— is that today, precisely because of the greatness of his knowledge and power, man will fail to face up the question of the truth. This would mean at the same time that reason would ultimately bow to the pressure of interests and attraction of utility, constrained to recognize this as the ultimate criterion. To put it from the point of view of the structure of the university: there is a danger that philosophy, no longer considering itself capable of its true task, will degenerate into positivism; and that theology, with its message addressed to the reason, will be limited to the private sphere of a more or less numerous group. Yet if reason out of concern for its alleged purity, becomes deaf to the great message that comes to it from Christian faith and wisdom, then it withers like a tree whose roots can no longer reach the water that gives life. It loses the courage for truth and thus becomes not greater but smaller.5

What the Pope indicts here is the unexamined negative framework of a secular reason— uncritically reductive and, in the end, unscientific because it is unhistorical and antihermeneutical—as the everyday default working paradigm for the self-understanding of the university qua university. It is interesting, to say the least, that the Pope’s concern is echoed in unexpected and surprising ways among those of the postmodern avant-garde who have come to realize that “secular reason” is a figment unable to account for itself let alone the comprehensive nature of the university as universitas.

Now to the final segment of my snapshot of the late-modern research university.

3. Stanley Fish, once upon a time chair of the English department at Duke and now a professor of humanities and law in Florida International University in Miami, recently introduced and discussed a noteworthy book by University of San Diego Warren Distinguished Professor of Law Steven D. Smith, The Disenchantment of Secular Discourse. Stanley Fish and Steven Smith attempt to break open from the inside what Charles Taylor once aptly called “the citadel of modern secular reason.” In his book Smith argues that “there are no secular reason… of the kind that could justify a decision to take one course of action rather than another.” Consider Fish’s apt summary of Smith’s argument:

Secular reason can’t do its own self-assigned job—of describing the world in ways that allow us to move forward in our projects—without importing, but not acknowledging, the very perspectives it pushes away in disdain. While secular discourse, in the form of statistical analyses, controlled experiments, and rational decisions-trees can yield banks of data that can then be subdivided and refined in more ways than we can count, it cannot tell us what data means or what to do with it. No matter how much information you pile up and how sophisticated are the analytical operations you perform, you will never get one millimeter closer to the moment when you can move from the piled-up information to some lesson or imperative it points to.6

Now, in a certain way, this is not surprising under the considerations of the modern dismissal of ontological and moral teleology. This profound incapability is in fact just what we should expect from secular reason and a university committed to it. But there is a deeper and more unsettling problem—the self-deception of secular reason about its own “sleight of hand.” Consider again Fish on Smith’s book:

Nevertheless, Smith observes, the self-impoverished discourse of secular reason does in fact produce judgments, formulates and defends agendas, and speaks in a normative vocabulary. How does it manage? By “smuggling,” Smith answers. “The secular vocabulary within which public discourse is constrained today is insufficient to convey our full set of normative convictions and commitments. We manage to debate normative matters anyway—but only by smuggling in notions that are formally inadmissible, and hence that cannot be openly acknowledged or adverted to.” The notions we must smuggle in, according to Smith, include “notions about purposive cosmos, or a teleological nature stocked with Aristotelian ‘final causes’ or ‘providential design,’” all banished from secular discourse they stipulate truth and value in advance rather than waiting for them to be revealed by the outcomes of rational calculation. But if secular discourse needs notions like these to have a direction—to even get started—“we have little choice except to smuggle [them] into the conversations—to introduce them incognito under some sort of secular disguise.”7

Fish’s analysis of Smith’s argument rings true. For every university reflects unavoidably to at least some degree the culture it arises from and operates in. The late-modern research university has to a large degree embraced the  «In Leisure: The Basis of Culture, the German philosopher Joseph Pieper reminds us of this all-important correlation: Strictly speaking, a claim for academic freedom can only exist when the “academic” itself is realized in a “philosophical” way. And this is historically the reason: academic freedom has been lost, exactly to the extent that the philosophical character of academic study has been lost, or, to put it another way, to the extent that the totalitarian demands of the working world have conquered the realm of the university. Here is where the metaphysical roots of the problem lie: the “politicization” is only a symptom and consequence. And indeed, it must be admitted here that this is nothing other than the fruit… of philosophy itself, of modern philosophy!»assumption of secular reason and is committed to serving an allegedly shared, non-partisan discourse of “public reason,” with its many unquestionable and indeed staggering accomplishments. This, however, is an illusion and, a disastrous one at that. For inside the self-imposed limitations of “secular reason” the university qua university becomes unintelligible to itself. All it can be for “secular reason” is a convenient agglomeration of facilities and competencies proximate to each other, branded and marketed under one single name, but each receiving its justification in light of distinct and largely incommensurable needs from vastly varied segments of advanced, diversified, and technologically driven society. “Secular reason” has intentionally cut itself off from the intellectual and moral sources that would allow it to acknowledge and advance the overarching teleology that gives intrinsic value to the university as such: the mind being ordered to truth and the corresponding search for truth and the ordering or these truths—which is the task of wisdom.

«In Leisure: The Basis of Culture, the German philosopher Joseph Pieper reminds us of this all-important correlation: Strictly speaking, a claim for academic freedom can only exist when the “academic” itself is realized in a “philosophical” way. And this is historically the reason: academic freedom has been lost, exactly to the extent that the philosophical character of academic study has been lost, or, to put it another way, to the extent that the totalitarian demands of the working world have conquered the realm of the university. Here is where the metaphysical roots of the problem lie: the “politicization” is only a symptom and consequence. And indeed, it must be admitted here that this is nothing other than the fruit… of philosophy itself, of modern philosophy!»assumption of secular reason and is committed to serving an allegedly shared, non-partisan discourse of “public reason,” with its many unquestionable and indeed staggering accomplishments. This, however, is an illusion and, a disastrous one at that. For inside the self-imposed limitations of “secular reason” the university qua university becomes unintelligible to itself. All it can be for “secular reason” is a convenient agglomeration of facilities and competencies proximate to each other, branded and marketed under one single name, but each receiving its justification in light of distinct and largely incommensurable needs from vastly varied segments of advanced, diversified, and technologically driven society. “Secular reason” has intentionally cut itself off from the intellectual and moral sources that would allow it to acknowledge and advance the overarching teleology that gives intrinsic value to the university as such: the mind being ordered to truth and the corresponding search for truth and the ordering or these truths—which is the task of wisdom.

In the same speech for Rome´s La Sapienza University, Benedict pointed to the self-deception of secular reason. “If our culture seeks only to build itself on the basis of the circle of its own argumentation and what convinces it on the time, and if—anxious to preserve its secularism—it detaches itself from its life-giving roots, then it will fall apart and disintegrate.”8 Like late-modern society, the late-modern research university lives from intellectual and moral sources it cannot account for, let alone produce. The university’s third dimension, however, seems to depend precisely on such intellectual and moral sources.

The third dimension is the unifying dimension that offers an integrative and ordered view of the first two dimensions and hence enables coherence, order, and evaluation—and pedagogically paideia. It is the dimension of “meta-science,” of a unifying and integrating inquiry that transcends each particular science and the acquiring of specific competencies. It is an inquiry that attends to the whole, to the order and coherence of all science, to its governing principles, and hence to the university as a self-conscious and coherent search for truth and wisdom, forming an ellipsis around two foci: the universe and the human being. The third dimension, the depth-dimension, offers internal coherence to a university education and realizes the university in a strong and proper sense. Whatever makes a university sill a somewhat, even marginally, coherent reality is parasitical on this third, depth dimension. Inasmuch as the late-modern research university embraces “secular reason” as its dominant mode of self-understanding and of meditation, it closes itself off from this third dimension and restricts itself to the two-dimensional plane of the production of knowledge. I would like to highlight two features of this third dimension by way of a philosophical observation and a theological reminder.

A philosophical observation

First the philosophical observation that brings me again to Fish’s interpretation of Smith’s The Disenchantment of Secular Discourse:

Smith does not claim to be saying something wholly new. He cites David’s Hume declaration that by itself “reason is incompetent to answer any fundamental question,” and Alasdair MacIntyre’s description in After Virtue of modern secular discourse as consisting “of the now incoherent fragments of a kind of reasoning that make sense on older metaphysical assumptions.” And he might have added Augustine’s observation in De Trinitate that the entailment of reason cannot unfold in the absence of a substantive proposition that it did not and could not generate.9

In this pregnant passage, as well as elsewhere in his essay, Fish seems to suggest the return of metaphysics by way of the resurgence of two ultimately irrepressible realities: teleology and transcendence of human reason. What is the gesturing toward? Instead of entering a protracted discussion of these deep matters, let me take a shortcut by offering two citations of placeholders. First, MacIntyre says in God, Philosophy, Universities that “the ends of education… can correctly develop only with reference to the final end of human beings and the ordering of the curriculum has to be an ordering to that final end. We are able to understand what the university should be only if we understand what the universe is.”10 In short, if the university is to be coherently a university in the full sense of the term, it needs to embark upon inquiries that depend upon principles that “secular reason” can neither produce nor account for.

What is even more important to realize is that, arguably, the full recovery of meta-scientific inquiry is correlated to an equally full recovery of genuine academic freedom. In Leisure: The Basis of Culture, the German philosopher Joseph Pieper reminds us of this all-important correlation:

Strictly speaking, a claim for academic freedom can only exist when the “academic” itself is realized in a “philosophical” way. And this is historically the reason: academic freedom has been lost, exactly to the extent that the philosophical character of academic study has been lost, or, to put it another way, to the extent that the totalitarian demands of the working world have conquered the realm of the university. Here is where the metaphysical roots of the problem lie: the “politicization” is only a symptom and consequence. And indeed, it must be admitted here that this is nothing other than the fruit… of philosophy itself, of modern philosophy!11

Instead of modern philosophy, Pieper could as well have said “secular reason.” His point is that true academic freedom is a freedom that is realized fully in the university’s third dimension, a dimension that is accessible from each university discipline. Differently put, the integrating and ordering function of the third dimension is not extrinsically imposed upon the various academic disciplines but arises from what Pieper calls the “philosophical” character of academic study per se by way of which each discipline transcends itself in the very pursuit of its distinct subject matter.

The theological reminder

Now, from the philosophical observation to the theological reminder. The theological reminder is simply this: the university’s third dimension flourishes to the fullest if enlightened from above. As long as God is the end of the pursuit of wisdom and theology, natural and revealed, is the capstone of the university’s disciplines, then the third dimension will never collapse, and the university will remain universitas in the full sense of the term. It was this theological reminder that has kept pre-modern Christian universities aware of the fact that the primordial human estrangement from God is a fundamental estrangement that left a wound in the human being, a wound that affected the will most strongly of all the human faculties. In light of the knowledge that the third dimension yields, Newman in his typically succinct way formulates a serious reservation that indicates the limitation of even the best kind of university education one can hope for, the best kind yielded by a university whose third dimension is in full bloom, so to speak. I cite again from his 1852 Dublin lectures, The Scope and Nature of University Education:

Knowledge is one thing, virtue is another; good sense is not conscience, refinement is not humility, nor is largeness and justness of view faith. Philosophy, however enlightened, however profound, gives no command over the passions, no influential motives, no vivifying principles. Liberal education makes not the Christian, not the Catholic, but the gentleman… Quarry the great rock with razors, or moor the vessel with a thread of silk; then may you hope with such keen and delicate instruments as human knowledge and human reason to contend against those giants, the passion and the pride of man… Liberal education, viewed in itself, is simply the cultivation of the intellect, as such, and its object is nothing more or less than intellectual excellence.12

On one level, the most fundamental one from a theological point of view, Newman is right: liberal education is meant not for the cultivation of the saint, but for the cultivation of the intellect; the university is meant for the excellence that characterizes the saint. The gentleman Newman invokes should, I think, be understood as an intellectually well-formed socially competent person. But here I think Newman is granting a point tacitly that at other instances in his work he was willing to support explicitly: that paideia, the formation of character, is integral to a university education. For, arguably, the formation of intellectual virtues occurs best in conjunction with the formation of character; differently put: a deficient or absent character formation complicates or even obstructs the proper formation of the intellectual virtues.

Because the virtues of the mind—development of which is integral to the university’s third dimension—cannot be divorced from the formation of character, that is the formation in the moral virtues, we can now specify more clearly the twofold way in which the university matters, especially after the disenchantment of secular reason. This brings me to the final part of my article.

I do not indulge in the illusion that one can save the university in one sabbatical, let alone in the course of a single article. But one can begin to think in different ways about different things and ask different questions. The university is a privileged place, a precious institution, and it is a great honor to teach in this institution: it is an institution that matters greatly, but cut off from its own intellectual and historical roots, from normative philosophical and theological traditions, it has largely forgotten it actually matters. It matters because of the truth and because the human being is made for the truth. That is the surpassing dignity of the human being in which the dignity of the university participates. To ask secular reason’s dismissive question, “What is truth?” is to lose the dignity of the human being as well as the dignity of the university.

What would it mean to recover this dignity in full? As I mentioned in my introduction, two practices are essential for its full development and flourishing: leisure or school and paideia. The practice of leisure has as its intrinsic end the integration of the sciences, the contemplation of the whole, in short, the search of wisdom. The practice of leisure is the only practice that allows something like the self-reflexivity of the university as university. (The integration thus brought is, however, radically different from the kind of interdisciplinarity that is meant to produce just another kind of data, another kind of useful knowledge to be applied here or there).

Second, the practice of paideia aims at an integral human formation of character, the formation of the intellectual virtues in conjunction of the moral virtues. There is no paideia without leisure, and true leisure flourishes in paideia.

Let me turn to paideia first and begin with an unlikely voice of concern. In his 2004 novel, I Am Charlotte Simons, Tom Wolfe offers a trenchant exposé of contemporary American university life that only seems to confirm Newman’s position about contending against “the passion and the pride of man.” While describing the drug-abuse, alcoholism, and sexual promiscuity that characterize late-modern secular American college and university life, Wolfe clearly also seems to expect more from colleges and universities than simply to mimic the cultural and moral destitution of the wider society. In a conversation with an interviewer, Wolfe said that he deplored the fact that “with a few exceptions, universities have totally abandoned the idea of strengthening character.”13 Are Wolfe’s expectations of the idea of the late-modern university hopelessly naïve, outmoded, and ultimately utopian or might they reflect some understanding of the connection between character formation and the pursuit of wisdom?

It is noteworthy and should give those who care about these matters pause that on this very point the Thomistic students of Aristotle and the Augustinian students of Plato are in full agreement, and that, therefore, Benedict XVI shares Tom Wolfe’s expectation of character formation to be an integral component of a university education that serves that name. On September 27, 2009, in his address to representatives of the members of the academic community of the ancient Charles University in Prague, Benedict states: “From the time of Plato, education has been not merely the accumulation of knowledge and skills, but paideia, human formation in the treasures of an intellectual tradition directed to virtuous life… The idea of an integrated education, based on the unity of knowledge grounded in truth, must be regained.”14 How this paideia is exactly to be understood needs further development. What seems obvious is that in order to engage in the pursuit of the unity of knowledge— wisdom—one must be formed in those intellectual virtues requisite for such pursuit to be successful. Less obvious is the correlation between the formation of the intellectual virtues and the formation of the moral virtues. In Aquinas’s doctrine of the cardinal virtues, prudence holds a principal position, for it is the one intellectual virtue that cannot be without moral virtue.15 Hence, like Newman, Aquinas can also account for the brilliant scoundrel. For prudence does not belong to those intellectual virtues that perfect the speculative intellect for the consideration of truth. But, unlike Newman, classical paideia and also Thomas expect from an university education more than the perfection of the strictly intellectual virtues; for the end of a proper liberal arts education is the pursuit of wisdom. And the pursuit of wisdom entails not only the refinement of habits of thought but also the habits of action; both pertain to the end of the human being. It is for this reason that paideia is integral to the pursuit of wisdom. And since prudence is the intellectual virtue that perfects reason pertaining to things to be done,16 the practice of paideia entails first and foremost the formation of prudence.

Paideia entails also the formation of other virtues such as truthfulness, studiousness, persistence, humility, collegiality— ordered and structured by temperance, that is, self-restraint, as well as by courage and justice. But what correlates paideia to the other central practice, leisure, is indeed prudence. Here we have the virtue that integrates both core practices of the university’s third dimension into the concrete life of each student—and forms the matter, of each professor, too.