Let me get up front to the central claim of my article1: What is increasingly missing from the late-modern research university and the kind of training it offers is what I shall call the university’s third dimension. For the American Association of Universities (AAU) this third dimension seems to have disappeared from the university. The first two dimensions of the late modern university constitute its “sharpness” as problem-solving institution: to intricate questions and to solve complex problems. The late modern university accomplishes this task by way of ever more specialized research and by way of a concomitant training of undergraduate and graduate students in the kind of expert knowledge that makes them competent problem-solvers. The university’s third dimension—constitutive of the classical university—comprises, first, scholē (in English “leisure”) that is, the structured practice of intellectual contemplation and reflection, and, second, paideia, that is, the integral formation of the intellectual virtues in conjunction with the development of the moral virtues. A university that lacks this third dimension might well be able to develop remarkable research, but, I think, will eventually suffer from a suffocating intellectual spiritual flatness that in the long run will prove detrimental to the university as such. In order to make good on this claim I will proceed through three steps. In the first step, I will offer a snapshot of the late-modern research university and highlight three of its noteworthy features: first, the remarkable ambivalence in contemporary academic thought pertaining to reason’s reliability and range, and, ultimately, to reason’s capacity for truth; second, the late-modern university’s pervasive embrace of the means of quantification or metrics for purposes of assessment and management (into which university administration seems to have largely morphed); and third, its embrace of the allegedly neutral framework of "secular reason" for its internal and external communication. These features belong essentially to what I regard as the university’s first and second dimension that together constitute the cutting edge, the utilitarian character of a highly complex problem-solving machine. The university’s third dimension, its depth dimension, refers to what has been at one time essential to the university qua university, that is, the pursuit of larger, comprehensive and integrating questions of truth and meaning—questions, I dare say, of metaphysics and morals. What is to be observed at the present moment regarding this third dimension are signs of a new emerging disenchantment with secular reason as the university’s governing principle, a disenchantment discernible as it seems first and foremost among some of the postmodern avant-gardes of the late-modern research university. ”

In a second step, I shall consider a brief philosophical observation and an equally brief theological reminder about the university’s third dimension.

In a concluding third step I will conclude that leisure and paideia are the two practices that keep the soul of the university alive and that will assure that the university qua university will continue to matter even under the specter of a comprehensive functionalization of the late-modern university—especially after the disenchantment of secular reason.

Like all thought, the normative perspectives that inform my critique of the late-modern research university and the concomitant university education come from somewhere. The perspective that informs the normative understanding of the university pursued here has its roots in the ancient paideia that came to flourish in the remarkable and still pertinent work of Thomas Aquinas. Obviously, this idea of university does not form the matrix on which the late-modern universities are built. However, I still hold as a governing principle for the subsequent reflections that a vision like the following is required as a critical normative standard in order to help us see at which point the “university” is in danger of becoming an equivocation (that is, a branding fraud). To quote Alasdair Mac- Intyre from his recent God, Philosophy, Universities: A Selective of the Catholic Philosophical Tradition: “The ends of education… can be correctly developed only with reference to the final end of human beings and the ordering of the curriculum has to be an ordering to that final end. We are able to understand what the university should be, only if we understand what the university is. But while this thought was crucial for Aquinas’s conception of the university, it was remarkable uninfluential in determining how universities in fact developed.”2

«Newman is right: liberal education is meant not for the cultivation of the saint, but for the cultivation of the intellect; the university is meant for the excellence that characterizes the saint. The gentleman Newman invokes should, I think, be understood as an intellectually well-formed socially competent person. But here I think Newman is granting a point tacitly that at other instances in his work he was willing to support explicitly: that paideia, the formation of character, is integral to a university education. For, arguably, the formation of intellectual virtues occurs best in conjunction with the formation of character.»

«Newman is right: liberal education is meant not for the cultivation of the saint, but for the cultivation of the intellect; the university is meant for the excellence that characterizes the saint. The gentleman Newman invokes should, I think, be understood as an intellectually well-formed socially competent person. But here I think Newman is granting a point tacitly that at other instances in his work he was willing to support explicitly: that paideia, the formation of character, is integral to a university education. For, arguably, the formation of intellectual virtues occurs best in conjunction with the formation of character.»

Describing and understanding the de facto development of universities in historical, sociological, and political terms is one kind of thing. Making sense of the university qua university on intellectual terms is another thing. I am pursuing only the latter here, and the presupposition of my talk is that the ideal reflected in Aquinas’s thought, and echoed to some degree under considerable different conditions in John Henry Newman’s 1852 Dublin lectures on The Scope and Nature of University Education, is far from obsolete. On the contrary, this ideal constitutes the corrective reminder and salutary challenge and is as such a program, I submit, superior to the Enlightenment model of the university as a place of advanced training in useful competencies, superior well to the Berlin-type and the Weberian version of the late-modern research university. For all these later models share the deficiencies of modernity; that is, they regard the university’s third dimension as dispensable and, if maintained, as at best a supererogatory concession to a luxury admitted for purely sentimental reasons, namely as one expedient way to honor the university’s pre-modern roots.

«For late modernity, that is, a thoroughly secularized and increasingly fragmented modernity, has now lost its optimistic élan and instead has become tired and cynical. In the agnostic world of irresistibly corruptible, interminably quarrelling, and tirelessly consuming bodies, hence a world in which the greatest dangers are disease, litigation, and the inability to consume, the hierarchy of university sciences stands in service of the avoidance of these evils: at the top stands the medical school supported by all the biomedical sciences, followed by the law school and the business school supported by their respective auxiliary sciences, first and foremost computer science and mathematics, but also any useful remnants of the liberal arts.»

Let me expand upon what I mean by the third dimension. In 2006, as an octogenarian, the philosopher Benedict Ashley published a simply remarkable book, a model of interdisciplinary rigor and comprehensiveness, The Way toward Wisdom: An Interdisciplinary and Intercultural Introduction to Metaphysics. Let me use his words to amplify this idea of the university’s third, integrative dimension.

The very term “university” means many-looking-toward-one, and is related to the term “universe,” the whole of reality. Thus, the name no longer seems appropriate to such a fragmented modern institution whose unity is provided only by a financial administration and perhaps a sports team. The fragmented academy is, of course, the result of the energetic exploration of all kinds of knowledge, but how can it meet the fundamental yearning for wisdom on which each culture is based?3

The search for wisdom characterizes the university’s third dimension and realizes the university qua university in a strict and proper sense. Hence, the university’s third dimension functions as critical norm that puts into stark relief strong tendencies—not recent in the origin, but recently gaining remarkable momentum—to reduce the university to a polytechnicum with a largely functionalized propaedeutic liberal arts appendix, this polytechnicum being largely an accidental agglomeration of advanced research competencies gathered in one facility for the sake of extrinsic and contingent convenience. If this trend should come to its logical term, if indeed each of these ad-vanced research competencies could be located elsewhere, that is, be directly linked to hospitals, to biochemical and computers companies, or to this or that branch of the military-industrial complex, without any lost, then the university in any substantive sense would have disappeared; and to still call what remains a university would be simply an equivocation, undoubtedly useful for reasons of branding and marketing, but hardly for reasons of substance.

A Snapshot of the Late-Modern Research University

1. It is hard to imagine a gulf deeper than the one that currently exists between those academics who regard reason in terms of utmost triumph and those who regard it in terms of utmost despair. Mathematically disciplined and technologically executed, human reason has transformed the globe in unprecedented ways. The academic disciplines based on reason’s mathematical and technological acumen hold a robust trust—if not faith—in reason’s capacity to grasp reality and, precisely because of this grasp, successfully to conform the world to human interest and needs.

Paradoxically, we can register a simultaneous widespread sense of despair about reason’s superior status and role. Instead of sovereignly guiding human affairs to their clear, defined, and well-considered ends, reason seems to be a little more than a coping mechanism or a regulative fiction driven and directed by instincts and desires it can hardly perceive, much less rule. The academic disciplines that traditionally draw upon reason’s reflective, integrative, and directive capacities— and exercised by humanity in the act of understanding and interpreting both world and self—seem to have fallen into a state of internal disarray while finding themselves exiled into what by all accounts seems to be a state of permanent marginalization within the late-modern research university. Reason triumphing in the form of instrumental rationality has produced its own demise as famously analyzed in Max Horkheimer and Theodore Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment.

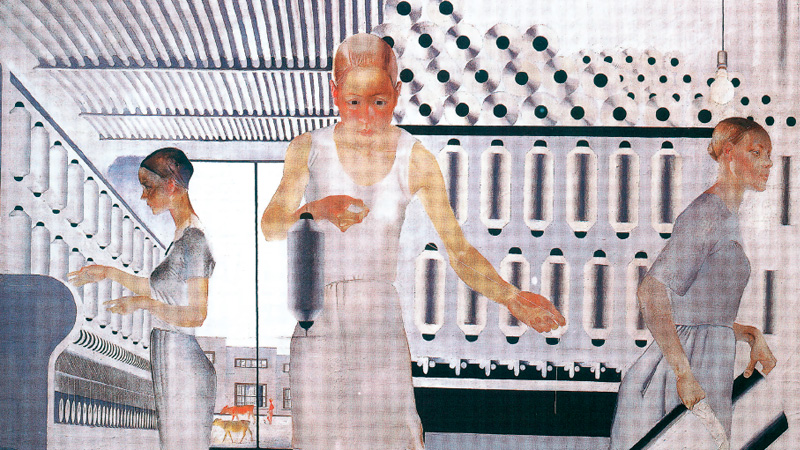

«Instrumental rationality and ontological nihilism seem to be two sides of the same coin. What is eclipsed in between is this question of truth. Because reason seems to have become incapable of attaining truth, it has to assert itself instead in the gigantomaniac demonstration and celebration of its instrumental effectiveness, its will to power. The prophet of this dynamic has been Friedrich Nietzsche. While Nietzsche was greatly disillusioned with the nineteenth century Berlin-style university, the late-modern, secular research university with its strong pragmatic and anti-metaphysical bent is more profoundly committed to some Nietzschean tenets that it seems to be aware.» Edward Hooper, Night Shadow, 1921.

«Instrumental rationality and ontological nihilism seem to be two sides of the same coin. What is eclipsed in between is this question of truth. Because reason seems to have become incapable of attaining truth, it has to assert itself instead in the gigantomaniac demonstration and celebration of its instrumental effectiveness, its will to power. The prophet of this dynamic has been Friedrich Nietzsche. While Nietzsche was greatly disillusioned with the nineteenth century Berlin-style university, the late-modern, secular research university with its strong pragmatic and anti-metaphysical bent is more profoundly committed to some Nietzschean tenets that it seems to be aware.» Edward Hooper, Night Shadow, 1921.

This arguable state of affairs is obviously not just an ivory-tower phenomenon, remote from and largely irrelevant to human society at large. Rather, the simultaneous triumph of and despair about reason mirrors late-modern society as such: we encounter breathtaking developments in artificial intelligence and biotechnology together with atmospheric epistemological skepticism and ontological nihilism that is as pervasive and erosive as it is elusive. Instrumental rationality and ontological nihilism seem to be two sides of the same coin. What is eclipsed in between is this question of truth. Because reason seems to have become incapable of attaining truth, it has to assert itself instead in the gigantomaniac demonstration and celebration of its instrumental effectiveness, its will to power. The prophet of this dynamic has been a German university professor of the nineteenth century, one who retired very early in his career from the university: Friedrich Nietzsche. While Nietzsche was greatly disillusioned with the nineteenth century Berlin-style university, the late-modern, secular research university with its strong pragmatic and anti-metaphysical bent is more profoundly committed to some Nietzschean tenets that it seems to be aware. Let me, for just one example, cite aphorism 480 from The Will to Power:

There exists neither “spirit,” nor reason, nor thinking, nor consciousness, nor soul, nor will, nor truth: all are fictions that are of no use. There is no question of the “subject and the object,” but of a particular species of animal that can prosper only through a certain relative rightness; above all, regularity of its perceptions (so that it can accumulate experience). Knowledge works as a tool of power. Hence it is plain that it increases with every increase of power. The meaning of “knowledge”: here, as in the case of “good” and “beautiful,” the concept is to be regarded in a strict and narrow anthropocentric and biological sense. In order for a particular species to maintain itself and increase its power, its conception of reality must comprehend enough of the calculable and constant for it to base a scheme of behavior on it. The utility of preservation—not some abstract-theoretical need not to be decided—stands as the motive behind the development of the organs of knowledge—they develop in such a way that their observations suffice for our preservation. In other words measure of the desire for knowledge depends upon the measure to which the will to power grows in a species: a species grasps a certain amount of reality in order become master of it in order to press it into service.

What would the kind of university look like in which Nietzsche’s understanding of the human being took hold, at least tacitly, of its self-understanding? This brings me to another segment of snapshot.

2. A university in which Nietzsche’s understanding of human being took hold would be, to say the least, profoundly ambivalent about itself—and remember, the best strategies to cope with ambivalence in matters of substance and teleology is quantification of metrics, instrumentalization, and management. It would also be a place in which philosophy would share an unequivocally marginal position with the other humanities, in which what once were the “liberal arts” would be characterized by curricular fragmentation and even disarray, and a place in which the biotechnological science would display an almost uncontrollable—should I say cancerous? —growth. Such a “university” —I put the  «In the speech for Rome´s La Sapienza University, Benedict pointed to the self-deception of secular reason. “If our culture seeks only to build itself on the basis of the circle of its own argumentation and what convinces it on the time, and if—anxious to preserve its secularism—it detaches itself from its life-giving roots, then it will fall apart and disintegrate.” Like late-modern society, the late-modern research university lives from intellectual and moral sources it cannot account for, let alone produce. The university’s third dimension, however, seems to depend precisely on such intellectual and moral sources.»word into quotation marks—would be first and foremost a highly sophisticated problem-solving machine at the service of those who are able and willing to pay for its service. In different, that is, more positive Benthamian terms: the late-modern research universities as they can be found across the globe are by and large institutions geared first and foremost to producing knowledge by way of highly specialized research (primarily in the natural and medical sciences), knowledge that is meant to serve interests that almost exclusively arise from the practical and technical needs and demand of the kinds of societies in which these universities are located. In a secondary way, these universities are geared to communicate this knowledge in order to produce specific competencies in their graduates. The undergraduate’s education—most lately blatant in Europe’s new Bologna system—is increasingly functionalized toward the acquisition of marketable skills and competencies. Added to these clearly defined, specialized competencies comes to stand an equally well defined set of so-called “Rahmen-Kompetenzen,” framework competencies. For it must be ensured that future Einsteins, Hawkings, Wittgensteins, Habermases and Auerbachs know how to lead effective small groups discussions, can organize laboratory teams, and prepare compelling Power-Point presentations.

«In the speech for Rome´s La Sapienza University, Benedict pointed to the self-deception of secular reason. “If our culture seeks only to build itself on the basis of the circle of its own argumentation and what convinces it on the time, and if—anxious to preserve its secularism—it detaches itself from its life-giving roots, then it will fall apart and disintegrate.” Like late-modern society, the late-modern research university lives from intellectual and moral sources it cannot account for, let alone produce. The university’s third dimension, however, seems to depend precisely on such intellectual and moral sources.»word into quotation marks—would be first and foremost a highly sophisticated problem-solving machine at the service of those who are able and willing to pay for its service. In different, that is, more positive Benthamian terms: the late-modern research universities as they can be found across the globe are by and large institutions geared first and foremost to producing knowledge by way of highly specialized research (primarily in the natural and medical sciences), knowledge that is meant to serve interests that almost exclusively arise from the practical and technical needs and demand of the kinds of societies in which these universities are located. In a secondary way, these universities are geared to communicate this knowledge in order to produce specific competencies in their graduates. The undergraduate’s education—most lately blatant in Europe’s new Bologna system—is increasingly functionalized toward the acquisition of marketable skills and competencies. Added to these clearly defined, specialized competencies comes to stand an equally well defined set of so-called “Rahmen-Kompetenzen,” framework competencies. For it must be ensured that future Einsteins, Hawkings, Wittgensteins, Habermases and Auerbachs know how to lead effective small groups discussions, can organize laboratory teams, and prepare compelling Power-Point presentations.

It was none other than Newman, who in his lectures on The scope and nature of the university—lectures more relevant than ever, I dare say—more than 150 years ago anticipates the specter of the late-modern research university. He discerns its seed in the scientific method of another of its founder fathers—Francis Bacon.

I cannot deny [Bacon] has abundantly achieved what he proposed. His is simply a Method whereby bodily discomforts and temporal wants are to be most effectually removed from the greatest number; and already, before it has shown any signs of exhaustion, the gifts of nature, in their most artificial shapes and luxurious profusion and diversity, from all quarters of the earth, are, it is undeniable, by its means brought even to our doors and we rejoice in them.4

But in the course of 150 years since Newman’s rather friendly characterization of the Baconian university, things have become considerably graver. For late modernity, that is, a thoroughly secularized and increasingly fragmented modernity, has now lost its optimistic élan and instead has become tired and cynical. In the agnostic world of irresistibly corruptible, interminably quarrelling, and tirelessly consuming bodies, hence a world in which the greatest dangers are disease, litigation, and the inability to consume, the hierarchy of university sciences stands in service of the avoidance of these evils: at the top stands the medical school supported by all the biomedical sciences, followed by the law school and the business school supported by their respective auxiliary sciences, first and foremost computer science and mathematics, but also any useful remnants of the liberal arts. And since it has been discovered that allegedly religious practice might contribute health and longevity, the gods are making a come-back, of sorts—now as an appendix to the medical school!

It is in light of these recent developments that the warning of Pope Benedict XVI—himself a long-time university professor profoundly committed to this unique institution of higher learning–—has an especially salient and sobering ring. The following is part of a speech that the Pope prepared in January of 2008 for the Roman university La Sapienza (once the Pope’s own university in Rome, now a secular Roman university), a speech that, however, was never delivered because at the last moment the university administration withdrew the invitation. Here is the pertinent passage, however:

The danger for the western world—to speak only of this— is that today, precisely because of the greatness of his knowledge and power, man will fail to face up the question of the truth. This would mean at the same time that reason would ultimately bow to the pressure of interests and attraction of utility, constrained to recognize this as the ultimate criterion. To put it from the point of view of the structure of the university: there is a danger that philosophy, no longer considering itself capable of its true task, will degenerate into positivism; and that theology, with its message addressed to the reason, will be limited to the private sphere of a more or less numerous group. Yet if reason out of concern for its alleged purity, becomes deaf to the great message that comes to it from Christian faith and wisdom, then it withers like a tree whose roots can no longer reach the water that gives life. It loses the courage for truth and thus becomes not greater but smaller.5

What the Pope indicts here is the unexamined negative framework of a secular reason— uncritically reductive and, in the end, unscientific because it is unhistorical and antihermeneutical—as the everyday default working paradigm for the self-understanding of the university qua university. It is interesting, to say the least, that the Pope’s concern is echoed in unexpected and surprising ways among those of the postmodern avant-garde who have come to realize that “secular reason” is a figment unable to account for itself let alone the comprehensive nature of the university as universitas.

Now to the final segment of my snapshot of the late-modern research university.

3. Stanley Fish, once upon a time chair of the English department at Duke and now a professor of humanities and law in Florida International University in Miami, recently introduced and discussed a noteworthy book by University of San Diego Warren Distinguished Professor of Law Steven D. Smith, The Disenchantment of Secular Discourse. Stanley Fish and Steven Smith attempt to break open from the inside what Charles Taylor once aptly called “the citadel of modern secular reason.” In his book Smith argues that “there are no secular reason… of the kind that could justify a decision to take one course of action rather than another.” Consider Fish’s apt summary of Smith’s argument:

Secular reason can’t do its own self-assigned job—of describing the world in ways that allow us to move forward in our projects—without importing, but not acknowledging, the very perspectives it pushes away in disdain. While secular discourse, in the form of statistical analyses, controlled experiments, and rational decisions-trees can yield banks of data that can then be subdivided and refined in more ways than we can count, it cannot tell us what data means or what to do with it. No matter how much information you pile up and how sophisticated are the analytical operations you perform, you will never get one millimeter closer to the moment when you can move from the piled-up information to some lesson or imperative it points to.6

Now, in a certain way, this is not surprising under the considerations of the modern dismissal of ontological and moral teleology. This profound incapability is in fact just what we should expect from secular reason and a university committed to it. But there is a deeper and more unsettling problem—the self-deception of secular reason about its own “sleight of hand.” Consider again Fish on Smith’s book:

Nevertheless, Smith observes, the self-impoverished discourse of secular reason does in fact produce judgments, formulates and defends agendas, and speaks in a normative vocabulary. How does it manage? By “smuggling,” Smith answers. “The secular vocabulary within which public discourse is constrained today is insufficient to convey our full set of normative convictions and commitments. We manage to debate normative matters anyway—but only by smuggling in notions that are formally inadmissible, and hence that cannot be openly acknowledged or adverted to.” The notions we must smuggle in, according to Smith, include “notions about purposive cosmos, or a teleological nature stocked with Aristotelian ‘final causes’ or ‘providential design,’” all banished from secular discourse they stipulate truth and value in advance rather than waiting for them to be revealed by the outcomes of rational calculation. But if secular discourse needs notions like these to have a direction—to even get started—“we have little choice except to smuggle [them] into the conversations—to introduce them incognito under some sort of secular disguise.”7

Fish’s analysis of Smith’s argument rings true. For every university reflects unavoidably to at least some degree the culture it arises from and operates in. The late-modern research university has to a large degree embraced the  «In Leisure: The Basis of Culture, the German philosopher Joseph Pieper reminds us of this all-important correlation: Strictly speaking, a claim for academic freedom can only exist when the “academic” itself is realized in a “philosophical” way. And this is historically the reason: academic freedom has been lost, exactly to the extent that the philosophical character of academic study has been lost, or, to put it another way, to the extent that the totalitarian demands of the working world have conquered the realm of the university. Here is where the metaphysical roots of the problem lie: the “politicization” is only a symptom and consequence. And indeed, it must be admitted here that this is nothing other than the fruit… of philosophy itself, of modern philosophy!»assumption of secular reason and is committed to serving an allegedly shared, non-partisan discourse of “public reason,” with its many unquestionable and indeed staggering accomplishments. This, however, is an illusion and, a disastrous one at that. For inside the self-imposed limitations of “secular reason” the university qua university becomes unintelligible to itself. All it can be for “secular reason” is a convenient agglomeration of facilities and competencies proximate to each other, branded and marketed under one single name, but each receiving its justification in light of distinct and largely incommensurable needs from vastly varied segments of advanced, diversified, and technologically driven society. “Secular reason” has intentionally cut itself off from the intellectual and moral sources that would allow it to acknowledge and advance the overarching teleology that gives intrinsic value to the university as such: the mind being ordered to truth and the corresponding search for truth and the ordering or these truths—which is the task of wisdom.

«In Leisure: The Basis of Culture, the German philosopher Joseph Pieper reminds us of this all-important correlation: Strictly speaking, a claim for academic freedom can only exist when the “academic” itself is realized in a “philosophical” way. And this is historically the reason: academic freedom has been lost, exactly to the extent that the philosophical character of academic study has been lost, or, to put it another way, to the extent that the totalitarian demands of the working world have conquered the realm of the university. Here is where the metaphysical roots of the problem lie: the “politicization” is only a symptom and consequence. And indeed, it must be admitted here that this is nothing other than the fruit… of philosophy itself, of modern philosophy!»assumption of secular reason and is committed to serving an allegedly shared, non-partisan discourse of “public reason,” with its many unquestionable and indeed staggering accomplishments. This, however, is an illusion and, a disastrous one at that. For inside the self-imposed limitations of “secular reason” the university qua university becomes unintelligible to itself. All it can be for “secular reason” is a convenient agglomeration of facilities and competencies proximate to each other, branded and marketed under one single name, but each receiving its justification in light of distinct and largely incommensurable needs from vastly varied segments of advanced, diversified, and technologically driven society. “Secular reason” has intentionally cut itself off from the intellectual and moral sources that would allow it to acknowledge and advance the overarching teleology that gives intrinsic value to the university as such: the mind being ordered to truth and the corresponding search for truth and the ordering or these truths—which is the task of wisdom.

In the same speech for Rome´s La Sapienza University, Benedict pointed to the self-deception of secular reason. “If our culture seeks only to build itself on the basis of the circle of its own argumentation and what convinces it on the time, and if—anxious to preserve its secularism—it detaches itself from its life-giving roots, then it will fall apart and disintegrate.”8 Like late-modern society, the late-modern research university lives from intellectual and moral sources it cannot account for, let alone produce. The university’s third dimension, however, seems to depend precisely on such intellectual and moral sources.

What Is the University’s “Third Dimension” About?

The third dimension is the unifying dimension that offers an integrative and ordered view of the first two dimensions and hence enables coherence, order, and evaluation—and pedagogically paideia. It is the dimension of “meta-science,” of a unifying and integrating inquiry that transcends each particular science and the acquiring of specific competencies. It is an inquiry that attends to the whole, to the order and coherence of all science, to its governing principles, and hence to the university as a self-conscious and coherent search for truth and wisdom, forming an ellipsis around two foci: the universe and the human being. The third dimension, the depth-dimension, offers internal coherence to a university education and realizes the university in a strong and proper sense. Whatever makes a university sill a somewhat, even marginally, coherent reality is parasitical on this third, depth dimension. Inasmuch as the late-modern research university embraces “secular reason” as its dominant mode of self-understanding and of meditation, it closes itself off from this third dimension and restricts itself to the two-dimensional plane of the production of knowledge. I would like to highlight two features of this third dimension by way of a philosophical observation and a theological reminder.

A philosophical observation

First the philosophical observation that brings me again to Fish’s interpretation of Smith’s The Disenchantment of Secular Discourse:

Smith does not claim to be saying something wholly new. He cites David’s Hume declaration that by itself “reason is incompetent to answer any fundamental question,” and Alasdair MacIntyre’s description in After Virtue of modern secular discourse as consisting “of the now incoherent fragments of a kind of reasoning that make sense on older metaphysical assumptions.” And he might have added Augustine’s observation in De Trinitate that the entailment of reason cannot unfold in the absence of a substantive proposition that it did not and could not generate.9

In this pregnant passage, as well as elsewhere in his essay, Fish seems to suggest the return of metaphysics by way of the resurgence of two ultimately irrepressible realities: teleology and transcendence of human reason. What is the gesturing toward? Instead of entering a protracted discussion of these deep matters, let me take a shortcut by offering two citations of placeholders. First, MacIntyre says in God, Philosophy, Universities that “the ends of education… can correctly develop only with reference to the final end of human beings and the ordering of the curriculum has to be an ordering to that final end. We are able to understand what the university should be only if we understand what the universe is.”10 In short, if the university is to be coherently a university in the full sense of the term, it needs to embark upon inquiries that depend upon principles that “secular reason” can neither produce nor account for.

What is even more important to realize is that, arguably, the full recovery of meta-scientific inquiry is correlated to an equally full recovery of genuine academic freedom. In Leisure: The Basis of Culture, the German philosopher Joseph Pieper reminds us of this all-important correlation:

Strictly speaking, a claim for academic freedom can only exist when the “academic” itself is realized in a “philosophical” way. And this is historically the reason: academic freedom has been lost, exactly to the extent that the philosophical character of academic study has been lost, or, to put it another way, to the extent that the totalitarian demands of the working world have conquered the realm of the university. Here is where the metaphysical roots of the problem lie: the “politicization” is only a symptom and consequence. And indeed, it must be admitted here that this is nothing other than the fruit… of philosophy itself, of modern philosophy!11

Instead of modern philosophy, Pieper could as well have said “secular reason.” His point is that true academic freedom is a freedom that is realized fully in the university’s third dimension, a dimension that is accessible from each university discipline. Differently put, the integrating and ordering function of the third dimension is not extrinsically imposed upon the various academic disciplines but arises from what Pieper calls the “philosophical” character of academic study per se by way of which each discipline transcends itself in the very pursuit of its distinct subject matter.

The theological reminder

Now, from the philosophical observation to the theological reminder. The theological reminder is simply this: the university’s third dimension flourishes to the fullest if enlightened from above. As long as God is the end of the pursuit of wisdom and theology, natural and revealed, is the capstone of the university’s disciplines, then the third dimension will never collapse, and the university will remain universitas in the full sense of the term. It was this theological reminder that has kept pre-modern Christian universities aware of the fact that the primordial human estrangement from God is a fundamental estrangement that left a wound in the human being, a wound that affected the will most strongly of all the human faculties. In light of the knowledge that the third dimension yields, Newman in his typically succinct way formulates a serious reservation that indicates the limitation of even the best kind of university education one can hope for, the best kind yielded by a university whose third dimension is in full bloom, so to speak. I cite again from his 1852 Dublin lectures, The Scope and Nature of University Education:

Knowledge is one thing, virtue is another; good sense is not conscience, refinement is not humility, nor is largeness and justness of view faith. Philosophy, however enlightened, however profound, gives no command over the passions, no influential motives, no vivifying principles. Liberal education makes not the Christian, not the Catholic, but the gentleman… Quarry the great rock with razors, or moor the vessel with a thread of silk; then may you hope with such keen and delicate instruments as human knowledge and human reason to contend against those giants, the passion and the pride of man… Liberal education, viewed in itself, is simply the cultivation of the intellect, as such, and its object is nothing more or less than intellectual excellence.12

On one level, the most fundamental one from a theological point of view, Newman is right: liberal education is meant not for the cultivation of the saint, but for the cultivation of the intellect; the university is meant for the excellence that characterizes the saint. The gentleman Newman invokes should, I think, be understood as an intellectually well-formed socially competent person. But here I think Newman is granting a point tacitly that at other instances in his work he was willing to support explicitly: that paideia, the formation of character, is integral to a university education. For, arguably, the formation of intellectual virtues occurs best in conjunction with the formation of character; differently put: a deficient or absent character formation complicates or even obstructs the proper formation of the intellectual virtues.

Because the virtues of the mind—development of which is integral to the university’s third dimension—cannot be divorced from the formation of character, that is the formation in the moral virtues, we can now specify more clearly the twofold way in which the university matters, especially after the disenchantment of secular reason. This brings me to the final part of my article.

What It Means to Reclaim the University’s Third Dimension: Leisure, Paideia, and Genuine Academic Freedom

I do not indulge in the illusion that one can save the university in one sabbatical, let alone in the course of a single article. But one can begin to think in different ways about different things and ask different questions. The university is a privileged place, a precious institution, and it is a great honor to teach in this institution: it is an institution that matters greatly, but cut off from its own intellectual and historical roots, from normative philosophical and theological traditions, it has largely forgotten it actually matters. It matters because of the truth and because the human being is made for the truth. That is the surpassing dignity of the human being in which the dignity of the university participates. To ask secular reason’s dismissive question, “What is truth?” is to lose the dignity of the human being as well as the dignity of the university.

What would it mean to recover this dignity in full? As I mentioned in my introduction, two practices are essential for its full development and flourishing: leisure or school and paideia. The practice of leisure has as its intrinsic end the integration of the sciences, the contemplation of the whole, in short, the search of wisdom. The practice of leisure is the only practice that allows something like the self-reflexivity of the university as university. (The integration thus brought is, however, radically different from the kind of interdisciplinarity that is meant to produce just another kind of data, another kind of useful knowledge to be applied here or there).

Second, the practice of paideia aims at an integral human formation of character, the formation of the intellectual virtues in conjunction of the moral virtues. There is no paideia without leisure, and true leisure flourishes in paideia.

Let me turn to paideia first and begin with an unlikely voice of concern. In his 2004 novel, I Am Charlotte Simons, Tom Wolfe offers a trenchant exposé of contemporary American university life that only seems to confirm Newman’s position about contending against “the passion and the pride of man.” While describing the drug-abuse, alcoholism, and sexual promiscuity that characterize late-modern secular American college and university life, Wolfe clearly also seems to expect more from colleges and universities than simply to mimic the cultural and moral destitution of the wider society. In a conversation with an interviewer, Wolfe said that he deplored the fact that “with a few exceptions, universities have totally abandoned the idea of strengthening character.”13 Are Wolfe’s expectations of the idea of the late-modern university hopelessly naïve, outmoded, and ultimately utopian or might they reflect some understanding of the connection between character formation and the pursuit of wisdom?

It is noteworthy and should give those who care about these matters pause that on this very point the Thomistic students of Aristotle and the Augustinian students of Plato are in full agreement, and that, therefore, Benedict XVI shares Tom Wolfe’s expectation of character formation to be an integral component of a university education that serves that name. On September 27, 2009, in his address to representatives of the members of the academic community of the ancient Charles University in Prague, Benedict states: “From the time of Plato, education has been not merely the accumulation of knowledge and skills, but paideia, human formation in the treasures of an intellectual tradition directed to virtuous life… The idea of an integrated education, based on the unity of knowledge grounded in truth, must be regained.”14 How this paideia is exactly to be understood needs further development. What seems obvious is that in order to engage in the pursuit of the unity of knowledge— wisdom—one must be formed in those intellectual virtues requisite for such pursuit to be successful. Less obvious is the correlation between the formation of the intellectual virtues and the formation of the moral virtues. In Aquinas’s doctrine of the cardinal virtues, prudence holds a principal position, for it is the one intellectual virtue that cannot be without moral virtue.15 Hence, like Newman, Aquinas can also account for the brilliant scoundrel. For prudence does not belong to those intellectual virtues that perfect the speculative intellect for the consideration of truth. But, unlike Newman, classical paideia and also Thomas expect from an university education more than the perfection of the strictly intellectual virtues; for the end of a proper liberal arts education is the pursuit of wisdom. And the pursuit of wisdom entails not only the refinement of habits of thought but also the habits of action; both pertain to the end of the human being. It is for this reason that paideia is integral to the pursuit of wisdom. And since prudence is the intellectual virtue that perfects reason pertaining to things to be done,16 the practice of paideia entails first and foremost the formation of prudence.

Paideia entails also the formation of other virtues such as truthfulness, studiousness, persistence, humility, collegiality— ordered and structured by temperance, that is, self-restraint, as well as by courage and justice. But what correlates paideia to the other central practice, leisure, is indeed prudence. Here we have the virtue that integrates both core practices of the university’s third dimension into the concrete life of each student—and forms the matter, of each professor, too.

Which brings us finally to the practice of leisure or scholē— the practice of a non-productive productivity. Differently put, the productivity in which leisure reaches its term—contemplation—remains essentially intrinsic to the practice of leisure. It cannot be functionalized for some extrinsic purpose. As such, leisure is the soul, the life principle of the university. Where scholē is gone, and with contemplation, meta-scientific is also lacking. In God, Philosophy, Universities, MacIntyre puts the matter most succinctly. To whom… in such a university falls the task of integrating the various disciplines, of considering the bearing of each on the others, of the nature and order of things? The answer is “No one,” but even this answer is misleading. For there is no sense in the contemporary American University that there is such a task, that something that matters is being left undone. And so the very notion of the nature and order of things, of a single universe, different aspects which are objects of enquiry for the various disciplines, but in such a way that each aspect needs to be related to every other, this notion no longer informs the enterprise of the contemporary American university. It has become an irrelevant concept.17 Is the practice of leisure and its intrinsic end, contemplation, a waste of time? It is exactly that. As Pieper has forcefully reminded us, leisure is the basis of culture. Without leisure, without that waste of time that escapes metric functionalization and managerial manipulation, in short, without the excess that contemplation always is, the university and the research it undertakes and the education it offers will be nothing but two-dimensional, that is, as flat as the blade of a circular saw, providing many cutting edges but no depth, or as ineffective as the razor scraping character from the rock. What gives a university and a university education depth and its unique dignity is what is in excess of “usefulness” (what the ancient would call “servility”). The artes liberals carry their end in themselves. And as such they always indicate the way of genuine academic freedom. It is the practice of leisure, however, that enables regular academic freedom to be realized as a freedom for excellence, which is nothing but a freedom for contemplation. I would hope that some of the Catholic colleges and universities in America at least will not only be found among those institutions of higher learning that defend the university’s third dimension but be first and foremost among those eager to return to this third dimension its original dignity and splendor.