Foreword by bishop Robert Barron

- Humanitas

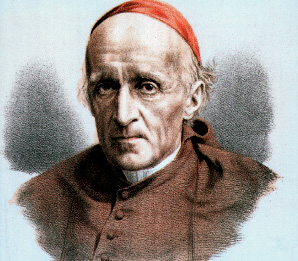

Before, during, and after the First Vatican Council, Newman adumbrated what I think we can call a mini-theology of Councils of the Church, which has much relevance for our own post-conciliar time. The first point to be made is that Newman was in no doubt that Councils had “ever been times of great trial.”

Since the Second Vatican Council was a council that was almost entirely concerned with the Church, the document in which the Council examines the very nature of the Church itself, Lumen Gentium, must surely be the most important. And it is in his ecclesiology that Newman perhaps most importantly anticipates the Council. Now it is of course only too well known that Newman was a lonely pioneer of the laity in the highly clerical Church of the nineteenth century, the author of what is held to be the classic text on the laity, his article “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine.” And there is no doubt that he would have welcomed the chapter on the laity in the Constitution. The other chapter that attracted most attention at the time of and after the Council was the chapter on the bishops. And Newman would certainly have seen this chapter as a necessary addition to and in that sense modification of the definition of papal infallibility at Vatican I, which had intended to produce a larger teaching about the Church, an intention that was frustrated by the indefinite suspension of the Council. To adapt his words about Pope St. Leo and the Council of Chalcedon, this chapter on the “apostolic college” (# 22), “without of course touching the definition” of the previous Council, “trimmed the balance of doctrine by completing it.”1

However, there are two other chapters, which have been comparatively ignored in comparison with the chapters on the laity and bishops, but which constitute the Council’s fundamental understanding of the nature of the Church and which were anticipated by Newman. I refer, of course, to the first two chapters, “The Mystery of the Church” and “The People of God,” which define in thoroughly scriptural and patristic terms the Council’s definition of what Newman would have called “the idea of the Church.” Here we find that same idea of the Church as Newman had discovered for himself as an Anglican from his reading of the Greek Fathers, who saw the Church as primarily the communion of those who have received the gift of the Holy Spirit in Baptism, the Church being therefore in Newman’s words the Holy Spirit’s “especial dwelling-place,” the Spirit having come “to make us one in Him who had died and was alive, that is, to form the Church,” “the one mystical body of Christ… quickened by the Spirit,” and “one” by virtue of the Spirit “giving it life.”2 Or, as Lumen Gentium puts it, “The Spirit dwells in the Church and in the hearts of the faithful as in a temple” (# 4), the people of God who “are reborn… from water and the Holy Spirit,” a “messianic people” in whom the Spirit “dwells as in a temple” (# 9). The two consequences of neglecting these two fundamental chapters and exaggerating the significance of the chapters on the bishops and the laity would, I suspect, have easily been predicted by Newman: namely, an excessively Gallican emphasis on so-called “collegiality,” an emphasis that ignores the fact that the Church is papal as well as episcopal, and a preoccupation with the laity which has led to what I call “laicism,” which has often taken the place of the old clericalism. In fact, a closer look at “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine” shows that, while certainly Newman does speak of the “laity” in the essay, the evidence he marshals from the time of the Arian heresy of the fourth century reveals that when he speaks of “the fidelity of the laity” the laity apparently include “holy virgins” and monks.3 Even more remarkably, a note Newman added in the appendix to the third edition of The Arians of the Fourth Century, when he republished it in 1871 in the collected uniform edition of his works, containing part of the original article, includes some amendments and additions, among which appears this extraordinary sentence: “And again, in speaking of the laity, I speak inclusively of their parish-priests (so to call them), at least in many places…”4 In other words, Newman in practice means by “the faithful” not simply the laity but what Lumen Gentium calls “the whole body of the faithful” (# 12), that is to say, he has the same conception of the Church as the organic communion of the baptized and not primarily as consisting of clergy and laity, an understanding that leads inexorably either to clericalism or to what I have called “laicism.”

Before, during, and after the First Vatican Council, Newman adumbrated what I think we can call a mini-theology of Councils of the Church, which has much relevance for our own postconciliar time. The first point to be made is that Newman was in no doubt that Councils had “ever been times of great trial”: history showed that they had “generally two characteristics—a great deal of violence and intrigue on the part of the actors in them, and a great resistance to their definitions on the part of portions of Christendom.”5

«Cardinal Manning had employed an extraordinary “rhetoric” in his pastoral letter of October 1870, which gave the impression that papal infallibility was unlimited.»Then there was the effect of a definition like that of papal infallibility: although in theory it might say very little, less than what the Ultramontanes had pressed for, the reality was that, “considered in its effects both upon the Pope’s mind and that of his people, and in the power of which it puts him in practical possession, it is nothing else than shooting Niagara.” The more general point here is that Councils have unintended consequences, larger consequences than the actual conciliar texts might seem to warrant; the more specific point is that a conciliar teaching cannot be taken in isolation out of context, or rather in this case lack of context, since the “definition was taken out of its order—it would have come to us very differently, if those preliminaries about the Church’s power had first been passed, which… were intended.”6 And Newman hoped that, if the suspended Council were able to reassemble, it would “occupy itself in other points” which would “have the effect of qualifying… the dogma.”7 What Newman is t hinking of here, of course, is a more general teaching about the Church that would have provided a context for papal infallibility. But that the Church had to wait for another Council for this to happen would not have surprised Newman: his study of the early Church showed how the Church “moved on to the perfect truth by various successive declarations, alternately in contrary directions, and thus perfecting, completing, supplying each other.” The definition of papal infallibility needed “to be completed” —“Let us be patient, let us have faith, and a new Pope, and a re-assembled Council may trim the boat.”8 That prophecy obviously came true with Pope John XXIII and the Second Vatican Council. But the general point about Councils needing “to be completed” applies no less to that later Council. And Newman means by completion not augmenting what has already been taught—which in the case of Vatican I would have meant a strengthening of the definition—but “declarations… in contrary directions.” In the case of Vatican II, it would suggest not a Vatican III, as many hoped at least until quite recently, that would “go further” than Vatican II, but rather “declarations… in contrary directions” to those of Vatican II, contrary not in the sense of contradictory but of different. The dogmas of the early Church, Newman observed, “were not struck off all at once but piecemeal—one Council did one thing, another a second—and so the whole dogma was built up.” What “looked extreme” needed to be “explained and completed.”9

«Cardinal Manning had employed an extraordinary “rhetoric” in his pastoral letter of October 1870, which gave the impression that papal infallibility was unlimited.»Then there was the effect of a definition like that of papal infallibility: although in theory it might say very little, less than what the Ultramontanes had pressed for, the reality was that, “considered in its effects both upon the Pope’s mind and that of his people, and in the power of which it puts him in practical possession, it is nothing else than shooting Niagara.” The more general point here is that Councils have unintended consequences, larger consequences than the actual conciliar texts might seem to warrant; the more specific point is that a conciliar teaching cannot be taken in isolation out of context, or rather in this case lack of context, since the “definition was taken out of its order—it would have come to us very differently, if those preliminaries about the Church’s power had first been passed, which… were intended.”6 And Newman hoped that, if the suspended Council were able to reassemble, it would “occupy itself in other points” which would “have the effect of qualifying… the dogma.”7 What Newman is t hinking of here, of course, is a more general teaching about the Church that would have provided a context for papal infallibility. But that the Church had to wait for another Council for this to happen would not have surprised Newman: his study of the early Church showed how the Church “moved on to the perfect truth by various successive declarations, alternately in contrary directions, and thus perfecting, completing, supplying each other.” The definition of papal infallibility needed “to be completed” —“Let us be patient, let us have faith, and a new Pope, and a re-assembled Council may trim the boat.”8 That prophecy obviously came true with Pope John XXIII and the Second Vatican Council. But the general point about Councils needing “to be completed” applies no less to that later Council. And Newman means by completion not augmenting what has already been taught—which in the case of Vatican I would have meant a strengthening of the definition—but “declarations… in contrary directions.” In the case of Vatican II, it would suggest not a Vatican III, as many hoped at least until quite recently, that would “go further” than Vatican II, but rather “declarations… in contrary directions” to those of Vatican II, contrary not in the sense of contradictory but of different. The dogmas of the early Church, Newman observed, “were not struck off all at once but piecemeal—one Council did one thing, another a second—and so the whole dogma was built up.” What “looked extreme” needed to be “explained and completed.”9

Although Vatican II was not for the most part a dogmatic Council, nevertheless its teachings caused and still cause considerable dissension. After Vatican I Newman had observed that the Church had had three hundred years to absorb and digest the Council of Trent, but “now we are new born children, the birth of the Vatican Council… We do not know what exactly we hold…”10 The unhappy fact was, Newman pointed out, that Councils “generally acted as a lever, displacing and disordering portions of the existing theological system,” leading to acrimonious controversy.11 Conciliar teachings require interpretation: they hardly speak for themselves, although after Vatican II there was much talk of “implementing” its teachings as though they were self-evident. Not only theologians have to “settle the force” of a teaching, just as “lawyers explain acts of Parliament,” but “the voice… of the whole Church diffusive” has to “make itself heard,” and “Catholic instincts and ideas” eventually “assimilate and harmonize” a conciliar teaching.12 There was what Newman called the “active infallibility” of popes and councils, but there was also what he called “the passive infallibility of t he whole body of t he Catholic people” in determining the force and meaning of the teachings.13 Given that one of the “disadvantages of a General Council, is that it throws individual units through the Church into confusion and sets them at variance,”14 Newman could hardly have been surprised by either the Old Catholic schism led by Döllinger and the extremism of the Ultramontane party in exaggerating the scope of the definition of papal infallibility. Nor would he have been surprised by the analogous if reverse situation after Vatican II when both Lefebvre and his followers and the liberals on the opposite wing united in exaggerating the revolutionary scope and meaning of the Council. However, although Newman deplored the way Döllinger appealed to history against the Council as analogous to the Protestant appeal to Scripture against the Church, he could not deny he had been provoked by the extreme Ultramontanes like Cardinal Manning who had employed extraordinary “rhetoric” in his pastoral letter of October 1870, which gave the impression that papal infallibility was unlimited.15 Similarly, he would no doubt have sympathized with the Lefebvrists to the extent that he would have deplored the aggressive extremism of Hans Küng and “the spirit of Vatican II” party.

Extract of the address of Benedict XVI to the Roman Curia, during his Christmas Greeting on December 22, 2005, where he explained the difference between an “hermeneutic of rupture” and an “hermeneutic of reform” in the interpretation of the Second Vatican Council.

(…) The question arises: Why has the implementation of the Council, in large parts of the Church, thus far been so difficult?

Well, it all depends on the correct interpretation of the Council or - as we would say today - on its proper hermeneutics, the correct key to its interpretation and application. The problems in its implementation arose from the fact that two contrary hermeneutics came face to face and quarrelled with each other. One caused confusion, the other, silently but more and more visibly, bore and is bearing fruit.

On the one hand, there is an interpretation that I would call “a hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture”; it has frequently availed itself of the sympathies of the mass media, and also one trend of modern theology. On the other, there is the “hermeneutic of reform”, of renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church which the Lord has given to us. She is a subject which increases in time and develops, yet always remaining the same, the one subject of the journeying People of God.

The hermeneutic of discontinuity risks ending in a split between the pre-conciliar Church and the post-conciliar Church. It asserts that the texts of the Council as such do not yet express the true spirit of the Council. It claims that they are the result of compromises in which, to reach unanimity, it was found necessary to keep and reconfirm many old things that are now pointless. However, the true spirit of the Council is not to be found in these compromises but instead in the impulses toward the new that are contained in the texts.

These innovations alone were supposed to represent the true spirit of the Council, and starting from and in conformity with them, it would be possible to move ahead. Precisely because the texts would only imperfectly reflect the true spirit of the Council and its newness, it would be necessary to go courageously beyond the texts and make room for the newness in which the Council’s deepest intention would be expressed, even if it were still vague.

In a word: it would be necessary not to follow the texts of the Council but its spirit. In this way, obviously, a vast margin was left open for the question on how this spirit should subsequently be defined and room was consequently made for every whim.

The nature of a Council as such is therefore basically misunderstood. In this way, it is considered as a sort of constituent that eliminates an old constitution and creates a new one. However, the Constituent Assembly needs a mandator and then confirmation by the mandator, in other words, the people the constitution must serve. The Fathers had no such mandate and no one had ever given them one; nor could anyone have given them one because the essential constitution of the Church comes from the Lord and was given to us so that we might attain eternal life and, starting from this perspective, be able to illuminate life in time and time itself.

Through the Sacrament they have received, Bishops are stewards of the Lord’s gift. They are “stewards of the mysteries of God” (I Cor 4:1); as such, they must be found to be “faithful” and “wise” (cf. Lk 12:41-48). This requires them to administer the Lord’s gift in the right way, so that it is not left concealed in some hiding place but bears fruit, and the Lord may end by saying to the administrator: “Since you were dependable in a small matter I will put you in charge of larger affairs” (cf. Mt 25:14-30; Lk 19:11-27).

These Gospel parables express the dynamic of fidelity required in the Lord’s service; and through them it becomes clear that, as in a Council, the dynamic and fidelity must converge.

The hermeneutic of discontinuity is countered by the hermeneutic of reform, as it was presented first by Pope John XXIII in his Speech inaugurating the Council on 11 October 1962 and later by Pope Paul VI in his Discourse for the Council’s conclusion on 7 December 1965.

Here I shall cite only John XXIII’s well-known words, which unequivocally express this hermeneutic when he says that the Council wishes “to transmit the doctrine, pure and integral, without any attenuation or distortion”. And he continues: “Our duty is not only to guard this precious treasure, as if we were concerned only with antiquity, but to dedicate ourselves with an earnest will and without fear to that work which our era demands of us...”. It is necessary that “adherence to all the teaching of the Church in its entirety and preciseness...” be presented in “faithful and perfect conformity to the authentic doctrine, which, however, should be studied and expounded through the methods of research and through the literary forms of modern thought. The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another...”, retaining the same meaning and message (The Documents of Vatican II,Walter M. Abbott, S.J., p. 715). (…)

It is precisely in this combination of continuity and discontinuity at different levels that the very nature of true reform consists. In this process of innovation in continuity we must learn to understand more practically than before that the Church’s decisions on contingent matters - for example, certain practical forms of liberalism or a free interpretation of the Bible - should necessarily be contingent themselves, precisely because they refer to a specific reality that is changeable in itself. It was necessary to learn to recognize that in these decisions it is only the principles that express the permanent aspect, since they remain as an undercurrent, motivating decisions from within. On the other hand, not so permanent are the practical forms that depend on the historical situation and are therefore subject to change. (…)

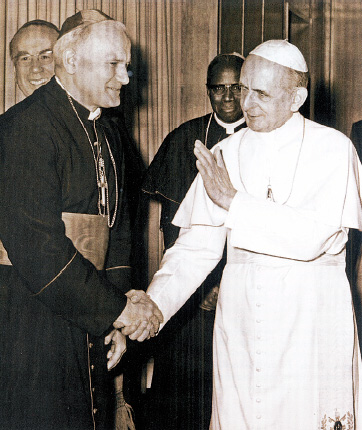

«After only nine years had elapsed, Pope Paul VI issued Evangelii Nuntiandi in 1974, in which he called for a new evangelization. Apart from the decree on the foreign missions, Vatican II was virtually silent on evangelization, which of course was to become the great theme of Pope John Paul II’s pontificate.»

«After only nine years had elapsed, Pope Paul VI issued Evangelii Nuntiandi in 1974, in which he called for a new evangelization. Apart from the decree on the foreign missions, Vatican II was virtually silent on evangelization, which of course was to become the great theme of Pope John Paul II’s pontificate.»

I want at this point to supplement these reflections on Councils and their aftermaths with a striking point that Newman makes at the beginning of his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. In the first section of the first chapter, where he is speaking about the process of development in ideas, he points out that a living idea cannot be isolated “from intercourse with the world around.” But he argues that this intercourse is actually necessary “if a great idea is duly to be understood, and much more if it is to be fully exhibited.” In Newman’s terminology, Christianity is just such an “idea.” Now there is an obvious objection to the argument: namely, that the further anything moves from its origin or source, the more likely it is to lose its original character. Conceding that certainly there is always a risk of an idea being corrupted by external elements, Newman nevertheless insists that, while “It is indeed sometimes said that the stream is clearest near the spring,” this is not true of the kind of idea he is talking about.

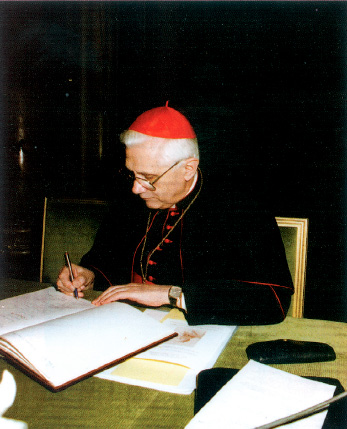

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, signs the guest book during the Academic Symposium “John Henry Newman— Lover of Truth” held in the Borromini Hall of the Chiesa Nuova in April 1990, organized to commemorate the centenary of the death of John Henry Newman.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, signs the guest book during the Academic Symposium “John Henry Newman— Lover of Truth” held in the Borromini Hall of the Chiesa Nuova in April 1990, organized to commemorate the centenary of the death of John Henry Newman.

“Whatever use may fairly be made of this image, it does not apply to the history of a philosophy or belief, which on the contrary is more equable, and purer, and stronger, when its bed has become deep, and broad, and full. It necessarily rises out of an existing state of things, and for a time savours of the soil. Its vital element needs disengaging from what is foreign and temporary…”16 In other words, the philosophy or belief becomes more rather than less its true self as it changes or develops in time. And it is ironic that the famous words which appear in the conclusion to this section are regularly quoted out of context to mean the opposite of what Newman intended: “In a higher world it is otherwise, but here below to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.” The point is not that Catholicism has to change or develop in order to be different, but in order to be the same, as the preceding sentence makes clear; “It changes with them [that is, external circumstances] in order to remain the same.”17

Now if Newman is correct in what he says about an “idea” such as “a philosophy or belief” becoming “more equable, and purer, and stronger” as it develops, then the teachings of Vatican II will become “more equable, and purer, and stronger” as time goes on. Those who participated in the Council no doubt thought they understood perfectly well the meaning of its teachings. Both Küng and Lefebvre had no doubt in their minds about how the Council was to be understood (as a rupture with Tradition), and, ironically, like Döllinger and Manning, were in close agreement about its significance. In retrospect, we can see much better the very limited scope of the definition of papal infallibility and appreciate the accuracy of Newman’s interpretation. But for both Döllinger and Manning the definition signified far more than Catholic theology has since understood it to mean—an understanding which received the Church’s formal endorsement at Vatican II. In the case of the latter Council, it similarly suited both Küng and Lefebvre to exaggerate the revolutionary nature of the Council, even though the so-called revolution aroused in them very different feelings. If it is appropriate to call Newman “the father of Vatican II,” then it is not unreasonable to apply the mini-theology of Councils which he adumbrated at the time of Vatican I, together with his theology of development, to the question of the reception and interpretation of Vatican II, as well as to likely future developments.

If we may take Newman as our guide, then, we may legitimately use that passage in the Essay on Development to argue that those who participated in or lived through the Second Vatican Council are less likely to understand the true meaning and significance of the Council’s teachings than posterity. The “idea” of Vatican II will, if Newman is correct, grow “more equable, and purer, and stronger” as the “stream” moves away from the “spring” and “its bed has become deep, and broad, and full.” Far from taking place in a historical void, the Second Vatican Council met at a time of enormous upheaval in Western society, a time of optimistic euphoria but also a time of great moral and spiritual devastation. It took place in a period of revolution and inevitably “savoured” of the “soil” of the 1960s, of, to use Newman’s words, the “existing state of things” of that decade. Consequently, its “vital element needs disengaging from what is foreign and temporary.” After Vatican I Newman constantly urged worried correspondents, “our duty is patience…” A year after that Council he wrote in a private letter: “Our wisdom is to… pray that He, who before now has completed a fifth Council by a second, may do so now.”18 Newman, of course, was praying not for another Council that would extend and strengthen the definition of papal infallibility as the Ultramontanes would doubtless have liked, but for a Council that would modify the definition by setting it in the larger perspective of a fuller teaching on the Church. In our time there has been no Vatican III that would have extended and strengthened the equivalent conciliar texts as the liberal wing of the Church would have liked, but rather the popes from Paul VI to Benedict XVI have endeavoured to set the teachings of the Council in the wider perspective of the whole history and tradition of the Church, so that the Council can be understood in continuity rather than rupture with the past.

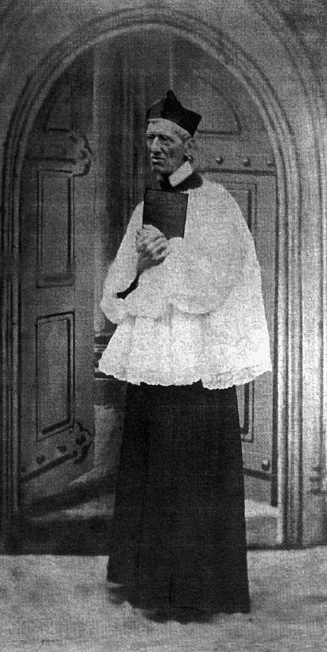

John Henry Newman in his Oratorian habit, in December 1861.This brings us to the second kind of development that Newman speaks of in his mini-theology of Councils. For it is not only a question of the meaning and significance of the “idea” of Vatican II becoming more luminous as it is seen both in the light of the past and in the developing life of the Church, but there is also the consideration that Councils open up further developments because of what they don’t say or stress. In the case of Vatican I, Newman saw that the isolated teaching on the papacy and the lack of a general teaching on the Church must open up the kind of development that would reach fruition nearly a century later in Lumen Gentium. The priorities similarly had to change after Vatican II, both because of unbalanced exaggerations of its teachings and because of the emergence of new problems. This change in fact began to happen very soon after the Council. After only nine years had elapsed, Pope Paul VI issued Evangelii Nuntiandi in 1974, in which he called for a new evangelization. Apart from the decree on the foreign missions, Vatican II was virtually silent on evangelization, which of course was to become the great theme of Pope John Paul II’s pontificate. These two kinds of development have come together in a wholly unexpected post-Vatican II phenomenon, which is vitally connected with the new evangelization, and which exemplifies both the two kinds of Newmanian development that I have been speaking of. The rise of the new ecclesial communities and movements, some of which in fact pre-date the Council, on the one hand can be said to represent a response to what the Council failed or omitted to speak about, and on the other hand to make much clearer and more luminous the first two chapters of Lumen Gentium, which I have argued must be the key text of the Council, by realizing in the concrete their real meaning and significance. For the whole point, one might say, about these communities and movements is precisely that they are not lay communities and movements, although they have been often called such, but ecclesial communities and movements. They are ecclesial and not lay because they consist not only of lay members but also of clergy, bishops, and religious or consecrated lay members. For what is so significant is that they bring together the baptised, whatever their particular status in the Church, into an organic communion. It was this organic communion that Newman portrayed in the Church of the fourth century in his article “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine.” And it is this same organic communion of the baptised that is the subject of the first two chapters of Lumen Gentium, which absolutely avoid speaking of the Church in the usual clerical/lay terms and where the terms do not even occur, the “ministerial or hierarchical priesthood” being simply referred to in connection with the sacrament of holy orders when the seven sacraments which build up the “common priesthood of the faithful” are listed (# 10-11).

John Henry Newman in his Oratorian habit, in December 1861.This brings us to the second kind of development that Newman speaks of in his mini-theology of Councils. For it is not only a question of the meaning and significance of the “idea” of Vatican II becoming more luminous as it is seen both in the light of the past and in the developing life of the Church, but there is also the consideration that Councils open up further developments because of what they don’t say or stress. In the case of Vatican I, Newman saw that the isolated teaching on the papacy and the lack of a general teaching on the Church must open up the kind of development that would reach fruition nearly a century later in Lumen Gentium. The priorities similarly had to change after Vatican II, both because of unbalanced exaggerations of its teachings and because of the emergence of new problems. This change in fact began to happen very soon after the Council. After only nine years had elapsed, Pope Paul VI issued Evangelii Nuntiandi in 1974, in which he called for a new evangelization. Apart from the decree on the foreign missions, Vatican II was virtually silent on evangelization, which of course was to become the great theme of Pope John Paul II’s pontificate. These two kinds of development have come together in a wholly unexpected post-Vatican II phenomenon, which is vitally connected with the new evangelization, and which exemplifies both the two kinds of Newmanian development that I have been speaking of. The rise of the new ecclesial communities and movements, some of which in fact pre-date the Council, on the one hand can be said to represent a response to what the Council failed or omitted to speak about, and on the other hand to make much clearer and more luminous the first two chapters of Lumen Gentium, which I have argued must be the key text of the Council, by realizing in the concrete their real meaning and significance. For the whole point, one might say, about these communities and movements is precisely that they are not lay communities and movements, although they have been often called such, but ecclesial communities and movements. They are ecclesial and not lay because they consist not only of lay members but also of clergy, bishops, and religious or consecrated lay members. For what is so significant is that they bring together the baptised, whatever their particular status in the Church, into an organic communion. It was this organic communion that Newman portrayed in the Church of the fourth century in his article “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine.” And it is this same organic communion of the baptised that is the subject of the first two chapters of Lumen Gentium, which absolutely avoid speaking of the Church in the usual clerical/lay terms and where the terms do not even occur, the “ministerial or hierarchical priesthood” being simply referred to in connection with the sacrament of holy orders when the seven sacraments which build up the “common priesthood of the faithful” are listed (# 10-11).

This movement of the Spirit has been a novel and often unpopular phenomenon in a Church that had grown increasingly clericalised until the Second Vatican Council’s emphasis on the laity provoked a sharp reaction in favour of a laicised Church. However, the phenomenon was entirely in continuity not disruption with the Church’s tradition insofar as it was simply another manifestation of the Church’s charismatic as opposed to hierarchical dimension. This charismatic dimension is in fact referred to three times in the first two chapters of Lumen Gentium. And this rediscovery of the charismatic dimension as one of the Church’s “constitutive elements” Pope John Paul II described as one of the most important achievements of the Council.19

Lumen Gentium employed the new theological term “charism,” a transliteration of the New Testament Greek word charisma in place of the Thomist phrase gratia gratis data (“grace freely given”). Naturally enough, then, Newman does not use the word. However, the idea of special graces given to individuals for the benefit of the Church was very much part of Newman’s thinking both as an Anglican and as a Catholic.

The Anglican Newman well understood the immense significance of the monastic charism when the Church was no longer persecuted but had become the state religion and was in danger of becoming too much of this world. The “one great purpose answered” by monasticism, he wrote, “was the maintenance of the Truth in times and places in which great masses of Catholics had let it slip from them.” At a time when Christians were in danger of becoming “secular,” monasteries became “the refuge of piety and holiness.” Indeed, Newman adds, “such provisions, in one shape or other, will always be attempted by the more serious and anxious part of the community, whenever Christianity is generally professed.” In other words, the charismatic dimension of the Church is essential for Christians wishing to practise their faith in a more committed and devout way. Where no spiritual outlet exists for more serious Christians, they will be liable to “run into separatism,” “by way of searching for something divine and transcendental,” as in Protestant countries “where monastic orders are unknown.” Like Lumen Gentium, Newman is insistent that the charisms need the hierarchy to regulate them: “enthusiasm is sobered and refined by being submitted to the discipline of the Church, instead of being allowed to run wild externally to it.”20

Newman was well aware the charisms are not given simply for the benefit of the recipient, but are intended for the whole Church. They therefore are the Holy Spirit’s answer to the particular needs of the Church at the time. And so, he wrote as a Catholic, while “St. Benedict had come as if to preserve a principle of civilization, and a refuge for learning, at a time when the old framework of society was falling, and new political creations were taking their place… when the young intellect within them began to stir, and a change of another kind discovered itself, then appeared St. Francis and St. Dominic…” Finally, Newman concludes, “in the last era of ecclesiastical revolution” the charism of St. Ignatius Loyola was given to the Church to meet new needs: “The hermitage, the cloister… and the friar were suited to other states of society; with the Jesuits, as well as with the religious Communities, which are their juniors,” the “chief objects of attention” were new kinds of apostolate, such as teaching and the missions.21

After his conversion, Newman became an Oratorian. Newman thought that the Oratorian charism was important in the Counter-Reformation for the reform of the diocesan clergy. Nevertheless, he also saw Oratorians as being in some respects like the early monks, who also did not take vows. For he thought the charism of St. Philip Neri was boldly to go back to primitive Christianity in its “plainness and simplicity,” not least in which, extraordinarily for the time, laymen participated.22 In a sermon of 1850, “The Mission of St. Philip,” he called Saints Benedict, Dominic, and Ignatius “the three venerable Patriarchs, whose Orders divide between them the extent of Christian history.” Certainly Philip was a minor charismatic figure compared with these giants, but nevertheless Newman points out that he “came under the teaching of all three successively.” Although he did not have the term “charism” in his theological vocabulary and although he lived at a time when the hierarchical dimension of the Church was exaggerated, Newman never underestimated the significance of the charismatic dimension. For these “masters in the spiritual Israel” had, “in an especial way,… had committed to them the office of a public ministry in the affairs of the Church one after another, and… are, in some sense, her nursing fathers.”23

«After his conversion, Newman became an Oratorian. Newman thought that the Oratorian charism was important in the Counter-Reformation for the reform of the diocesan clergy. Nevertheless, he also saw Oratorians as being in some respects like the early monks, who also did not take vows. For he thought the charism of St. Philip Neri was boldly to go back to primitive Christianity in its “plainness and simplicity,” not least in which, extraordinarily for the time, laymen participated.» St. Philip Neri.

«After his conversion, Newman became an Oratorian. Newman thought that the Oratorian charism was important in the Counter-Reformation for the reform of the diocesan clergy. Nevertheless, he also saw Oratorians as being in some respects like the early monks, who also did not take vows. For he thought the charism of St. Philip Neri was boldly to go back to primitive Christianity in its “plainness and simplicity,” not least in which, extraordinarily for the time, laymen participated.» St. Philip Neri.

In 1855 Newman gave a lecture entitled “The Three Patriarchs of Christian History, St. Benedict, St. Dominic, and St. Ignatius,” of which some notes survive.24 He had had it in mind, he wrote fifteen years later, to write a book on the “Historical contrast of Benedictines, Dominicans, and Jesuits, which I suppose I shall never finish.” In the end, he only managed to write the part on the Benedictines.25 It was a source of regret to him, he explained later, but, after what he had written on the Benedictines was criticized by a Benedictine abbot, he was nervous about trying to write about Dominicans, Franciscans, and Jesuits. One can only regret that Newman was never able to complete this book on these three great charismatic movements.

Finally, it is noteworthy that Newman actually anticipated the twentiethcentury ecclesial movements and communities, and not only through his ecclesiology of organic communion, but also in practice. For he himself led a movement in his own time, the Oxford or Tractarian Movement, which, far from being a clerical association as some of its initiators had wanted, consisted of both clergy and laity, some of its most prominent members being lay people. Later, at the time of the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in 1850, Newman hoped that a similar kind of movement might arise to support the Catholic cause, but the clerical nature of nineteenth-century Catholicism prevented this. Furthermore, Newman’s understanding of the original nature of Philip Neri’s Oratory shows how like a modern ecclesial community it had been to begin with. It had begun as an entirely lay community not as a priestly order or congregation. From this original community emerged a smaller community of priests but still closely linked to the larger lay community. Together, the congregation of priests and the lay community constituted the Oratory as one organic community.

The importance, then, that Newman attributed to the charismatic dimension of the Church is fully in accordance with the teaching of Lumen Gentium. In the sixteenth century the importance of the great charismatic figures of the Counter-Reformation can hardly be exaggerated. Without St. Ignatius Loyola and the Society of Jesus in particular it is hard to see how the reforms of the Council of Trent could have been implemented. Can we not similarly say that the true realization of the teachings of Vatican II, that is to say, a realization in continuity with rather than rupture with the Church’s tradition, is inseparable from the charisms that the Holy Spirit gave to the Church in the latter half of the twentieth century? Certainly, the ecclesial movements and communities, which Pope Benedict XVI has called the fifth great movement of the Spirit in the history of the Church,26 seem to manifest the two kinds of development that, according to Newman, would be the characteristic results of a Council.

Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, archbishop of Krakow, recalled details of that 10th of July 1979, when Pope John Paul II culminated his journey to Poland, unleashing an immense process of changes in Eastern Europe. He did so by means of an interview with journalists Marcin Przeciszewski and Tomasz Królak, of the Polish catholic agency Kai, revealing the huge effort accomplished then by Karol Wojtyla, who actually slept 14 hours running once back in Rome. —When did John Paul II begin to think about the possibility of visiting his fatherland? —Already a Cardinal, Karol Wojtyla attributed great importance to the celebration of the ninth centennial of the death of St. Stanislaw; he actually had been preparing the celebrations for a long time. He had sent invitations to all the Cardinals who had participated in the conclave of August 1978, and he also immediately invited John Paul I to Krakow. Therefore, from the first moment on since his election to the See of St. Peter it seemed obvious to him that he had to do everything what was possible in order to come to Poland to celebrate this anniversary. He felt that being in Krakow at that moment was a moral duty, even though he realized it would not be easy to accomplish.

Did he think the Polish communist authorities would not easily accept such a bitter drink?

As soon as the Polish rulers came to know about the request, they reacted in a negative way. But, meanwhile John Paul II had been officially invited to visit Mexico. He accepted with pleasure. For him, Latin America was very important because of the Theology of Liberation, that trend of interpreting the Social Teachings of the Church in perspective of Marxist ideology. And he thought: If I can go to Mexico, a country with the most anticlerical Constitution in the world, then even the Polish government will not be able to say no. He well remembered that the communist authorities had not allowed the visit of Paul VI. But he perceived intuitively that they would not be able to prevent his visit now.

When did the negotiations begin?

Quite soon. The negotiation was headed by the secretary of the Polish Bishop’s Conference, Monsignor Bronislaw Dabrowki. Finally, Warsaw gave free way, although with a condition: The Pope’s visit should not coincide with the anniversary of St. Stanislaw, in May. The Holy Father said: Well, that means I shall arrive the following month, in June.

And regarding the itinerary of the journey, were there any difficulties?

It was established the Pope wouldn’t travel further than the Vistula, that is, to the regions of eastern Poland. Silesia was also excluded. Basically, the Polish authorities wished that the Pope’s visit would be as brief as possible and very limited as to his moving from one place to another.

At the end, the difficulties were surmounted. Did John Paul II think about the possible repercussions of his journey? Did he realize that it would come to be so determining for the course of events in Poland?

Nobody could foresee that. He was convinced that the Polish nation, so deeply rooted in the Faith, deserved the visit of the Pope. At present we can undoubtedly say that his first pilgrimage to Poland was the most important of all the papal voyages, because it unleashed an incredible process of changes at world level. Everything began started during those days.

How did the Pope get ready for this journey?

He wrote himself all the texts of his speeches and homilies. The role of the Polish Section of the Department of State was limited to examine the quotes. He did not require any notes, he just relied on his memory. The Pope was perfectly organized and he wrote very fast: A long speech did not demand more than an hour and a half of his time. For a short speech, he took just an hour. And he read very much. He was able to do things at a time.

The central subject of his peregrination was the effusion of the Holy Spirit. It was quoted in almost every one of the Pope’s speeches. Was that a decision consulted with his collaborators?

John Paul II was a visionary, as many artists are. He knew what to say and what the Polish nation expected of him. He was able to present these subjects in the light of the Faith and the teachings of the Church. In addition, that period coincided with Pentecost.

But did John Paul II realize that his speech at Gniezno —in which he stated that the Slavic Pope’s mission was to make Europe discover the oneness of West and East— questioned the Vatican’s Ostpolitik which actually accepted the prevailing situation?

John Paul II always turned down the doctrine of “historical commitment”, in respect to which the West —and even the Church— should consider Marxism as a decisive element in the development of history. He was convinced that the future would not pertain either to Marxism or to class struggle. In this sense, he changes the Vatican’s policy in a decisive way. The change in perspective took many social groups and milieus to question if Marxism really was so strong. With the same firmness, John Paul II opposed the attempt to include Marxist analysis in the social teachings of the Church in the context of the Theology of Liberation. For him, Humanity’s development depended on the freedom to choose and human rights. He favoured private right and the untouchable dignity of the human being. The speech delivered at Gniezno marked the beginning of the iron curtain’s break down, which by then divided Europe. The break down of the wall began there, not in Berlin!

But, weren’t there worries, even in the Vatican, that John Paul II was going too far?

A statement so strong in favour of these rights in fact scared some people, including some members of the Church.

Doesn’t it annoy you that at present everybody speaks about the Wall in Berlin and not about Gniezno or about Solidarnosc?

One has to speak about historical facts. The fall of the Wall was a consequence of the process initiated in Poland in 1979, and I must repeat: The act of dismantling the iron curtain began in Gniezno, on June 3rd, 1979.

In Krakow, during his first journey, the Pope leant out a window of the archbishop’s see in order to talk to the youth, a dialog later repeated during each of his visits to Poland. Was that something planned in advance?

No, it was an absolutely spontaneous initiative. Thousands of people were expecting beneath that window and calling the Pope. It was necessary to show up somehow. The Holy Father made the decision all by himself, against the will of some around him, who tried to dissuade him for security reasons.

In your opinion, what is the deeper meaning of the Pope’s first peregrination to Poland?

—After that visit, Poland would never be the same again. The people straightened their backs; they lost their fear.

—Did Solidarnosc come to exist as a natural consequence of that liberation?

—John Paul II freed the inner energy of the Polish people. In that sense, he established the spiritual foundations for the coming into existence of Solidarnosc the year after.

—Once back in the Vatican, did John Paul II make any comment on his journey?

—He did not say anything because he had lost his voice. After returning, he was very tired; he slept fourteen hours running.

«Nobody could foresee it. John Paul II was convinced that the Polish nation, so deeply rooted in Faith, deserved the visit of the Pope. At present we can undoubtedly say that his first pilgrimage to Poland was the most important of all the papal voyages, because it unleashed an incredible process of changes at world level. Everything started during those days.»

«Nobody could foresee it. John Paul II was convinced that the Polish nation, so deeply rooted in Faith, deserved the visit of the Pope. At present we can undoubtedly say that his first pilgrimage to Poland was the most important of all the papal voyages, because it unleashed an incredible process of changes at world level. Everything started during those days.»

Let us talk about the martial law established by general Jaruzelski in December 1981. How did the Pope react?

John Paul II rarely showed any worry. But he spoke up strongly at Saint Peters basilica, in the presence of the Polish delegation, headed by President Jablonki. That happened in October 1982, when father Kolbe was cano-nized. The Pope said: “The [Polish] nation does not deserve what you have done”.

But had John Paul II considered the possibility of a Soviet invasion of Poland?

No one considered it seriously, because the Soviets were already engaged in Afghanistan. We were aware that the Soviet Union could not allow it by itself. We had precise information on that directly from the White House; we got it from Zbigniew Brzezinski [by then head of the US National Security Council], and from President Reagan himself, who personally called the Pope.

THE 1989 AVALANCHE

“The 1989 avalanche, which lasted until 1991, left us somewhat hypnotized; however, if we wish to understand what happened we must refer to the first stone that gave way, and which determined, progressively, the collapse. This first stone was dislodged in Poland. It was a movement of workers that, from reflection on their human condition, found spontaneously the Social Doctrine of the Church and formulated in her language their claims to take away legitimacy from a political regime that presented itself as the theoretic expression of the practical conscience of the Labor Movement […]. In other words, affirmed was the definitive rupture between theory and praxis within Marxism, which was questioned precisely by people whose conscience wished to constitute, in a reflective way, the workers.

“Evidenced from this premise was the irremediable crisis of Marxism, which first confronted the Polish oligarchy, and later also the Russian, with the following alternative: military dictatorship or reforms. The military dictatorship failed in Poland. Attempted in the Soviet Union was the way of reforms, but it turned out to be impracticable, and the result was the collapse of the regime.

“It is difficult to deny that there is in this process an ideal accident, and that at the beginning is the great witness of the Polish Church, led by Cardinal Stephan Wysynski, witness that extends and assumes a worldwide dimension with John Paul II’s pontificate.”

Rocco Buttiglione

El pensamiento de Karol Wojtyla. Ediciones Encuentro, Madrid.

What was the relationship between John Paul II and general Jaruzelski? He still says that martial law was the lesser evil when compared to a Soviet invasion.

The Pope never accepted such an interpretation. He respected Jaruzelski’s intellect and knowledge, but he did not agree with him in respect to anything. The general looked exclusively eastward. On the contrary, Edward Gierek, who, when saying goodbye to the Pope at the end of his journey, said: “Here, at Warsaw, blow winds from the west and from the east. Holy Father, keep alive those from the west”.

Have you ever felt the presence of the devil?

Yes, I have. The strongest was when the devil was driven out of a young woman. I was there and I know what it means. It is terrible to notice the presence of such an eminent and uncontrollable force. I saw him physically abusing her; I heard the voice with which he yelled at her. It happened after the general audience. John Paul II recited the exorcisms, but nothing! The Pope then said he would celebrate Mass on the next day for the purposes of the young woman. And, after that Mass, she suddenly felt as though she was another person, everything had vanished. At the beginning, I could hardly believe it; I thought it was some kind of mental illness. But, Satan does exist!

Now, how can one identify his presence in the world?

Satan exists, even though the prevailing ideology considers everything as a tale. At present, the devil works so that human beings will not believe he does exist. It is a very treacherous method.

Translated by Martín Bruggendieck

During the embryonic period of Japanese modernization in the second half of the 19th century.

The big words of those who prophesise a Church without God and without faith are pronounced in vain. We do not need a Church that celebrates the worship of action in political «prayers». It is absolutely superfluous and that is why it shall disappear on its own. The Church of Christ will remain –the Church that believes in the God who became man and who grants us life beyond death.

New Book: “The Pope Benedict XVI Reader”

07 May 2021Newman’s Rhetorical Strategies in Idea of a University

14 January 2019Passion for man

04 December 2018On Forgiveness

04 December 2018