How and why Newman rejects the understanding of doctrinal development as new revelation

- Christopher R. Mooney

How does his figure relate to ordinary people unfamiliar with philosophical or theological matters?

Address of His Holiness Paul VI to the Organizers and Members of the International Symposium on the Resurrection of Christ Saturday, April 4, 1970

We are most touched by the affectionate and confident words that Rev. P. Dhanis speaks to Us in your name, and We thank the Lord for this meeting, which He allows us to have with specialists highly-qualified in exegesis, theology, and philosophy, who have come (to Rome) to share fraternally their research on the mystery of the Resurrection of Christ.

Yes, We rejoice very much in this Symposium, which has been facilitated by the warm hospitality of the Institut Saint- Dominique on Via Cassia. We congratulate the organizers and all the members, whom We here receive most heartily, happy to express to them Our high esteem, Our particular good-will, and Our most lively encouragement.

In response to your expectations, We wish to share with you, in all simplicity, some thoughts that are suggested to Us by the central theme of the Resurrection of Jesus, which you have so happily chosen as the object of your work.

1) Is it necessary to begin by showing you the radical importance which, like all Our Christian sons and brothers, We attach to this study? And, We dare to say, the importance is still greater for Us, in the light of the position which the Lord has given Us in His Church – as privileged witness and guardian of the faith. Of this you are probably all well aware! Is not all the Gospel-history centered on the Resurrection? Without this, what would the Gospels themselves be, those Gospels which announce “the Good News of the Lord Jesus”? Do we not find there the source of all Christian preaching? (cf. Acts 2:32).

Does it not always remain the fulcrum of the whole epistemology of the faith, which, without it, would lose its consistency – as the Apostle Paul himself says: “If Christ be not risen... our faith is void” (cf. 1 Cor. 15:1-4).

Is it not this same Resurrection that alone gives meaning to all the Liturgy, to our “Eucharists,” assuring us of the presence of the Risen Christ, Whom we celebrate amid thanksgiving: “We proclaim your death, O Lord Jesus; we celebrate your Resurrection; we look forward to your return in glory” (Anamnesis). Yes, all Christian hope is based on the Resurrection of Christ, upon which is “anchored” our own resurrection along with Him. Indeed, even now we are risen with Him (cf. Col. 3:1) – the whole fabric of our Christian Life is woven through with this unfailing certainty and this hidden reality, along with the joy and dynamism which they produce.

“The Incredulity of Thomas”, Bernardo Strozzi’s oil painting, 1620.

“The Incredulity of Thomas”, Bernardo Strozzi’s oil painting, 1620.

2) So it is not surprising that such a mystery, so fundamental to our faith, so prodigious for our intelligence, has always aroused during the march of history not only the passionate interest of exegetes, but also multitudinous contestation. This phenomenon was already evident even during the lifetime of the evangelist, St. John, who thought it necessary to point out that the unbelieving Thomas was actually invited to touch with his hands the mark “of the nails and the blessed side of the risen ‘Word of Life’” (cf. Jn. 20:24-29).

Is not the same thing suggested later, in the efforts of a gnosis ever recurring under many forms, to penetrate this mystery by means of all the resources of the human spirit, and thus to reduce the mystery to the dimensions of merely human categories? These efforts are indeed understandable, and even inevitable, but they have a fearful penchant quietly to empty of all richness and significance that which is above all a fact: the resurrection of the Savior.

Even today –and you have certainly no need to be reminded of this– we see this tendency reveal its ultimate dramatic consequences, going so far as to deny, even among people who profess themselves Christians, the historical value of the inspired witness, or (more recently) to interpret the physical resurrection of Jesus in a way that is purely mythical, spiritual, or moral. Of course We are profoundly aware of the disintegrating effect “The Incredulity of Thomas”, Bernardo Strozzi’s oil painting, 1620. that such harmful discussions have upon many of the faithful. But –and We say this with emphasis– We regard all this without fear, since, today just as in the past, the witness of “the eleven and their companions” is capable, with the grace of the Holy Spirit, of arousing the true faith: “It is indeed true! The Lord has risen and has appeared to Peter” (Lk. 24:34-35).

3) It is in these sentiments that We regard with great respect the hermeneutical and exegetical work being done upon this fundamental theme, by qualified men of science like yourselves. Your attitude is conformed to the principles and norms which the Catholic Church has established for biblical studies. Let it suffice for Us to recall here the well-known encyclicals of Our predecessors: “Providentissimus Deus” of Leo XIII (1893) and “Divino Afflante Spiritu” of Pius XII (1943), as well as the recent Dogmatic Constitution Dei Verbum of Vatican II. Not only a healthy liberty of research is recognized, but also one finds recommended that effort which is needed in order to adapt the study of Sacred Scripture to the needs of today, and to “truly discover that which the sacred author willed to affirm” (Dei Verbum, 12).

Such a perspective retains the attention of the world of culture, and is a source of new enrichment for biblical studies. We are happy that it should be so.

As always, the Church appears as the jealous guardian of the written Revelation, and she shows herself animated today by a realist preoccupation: to use with discernment all knowledge and thought, in the critical interpretation of the biblical text. Thus the Church, while providing the means to know the thoughts of others, seeks to verify its own thinking and to provide occasions for meetings that are loyal and comforting for so many upright minds seeking the truth. Furthermore, the Church herself meets with the difficulties inherent in the exegesis of difficult or doubtful texts, and she approves the utility of having diverse opinions. St. Augustine has noted: “It is useful that many opinions be found concerning the obscurities of the divine Scriptures, by which God has willed to exercise us; it is useful that some should think differently from others, so long as all are in harmony with sound faith and doctrine” (Ep. ad Paulinum, 149, n. 34, P.L. 33, 644).

And the Church, still under the guidance of St. Augustine, exhorts her sons to seek for the solutions, by study joined with prayer: “Non solum admonendi sunt studiosi venerabilium Litterarum, ut in Scripturis sanctis genera locutionum sciant... verum etiam, quod est praecipuum et maxime necessarium, orent ut intelligant” (De Doctrina Christiana, III, 56: PL 34, 89).

4) But let Us return to the theme which is the object of your Symposium. It appears to Us, for Our part, that your various analyses and reflections tend to confirm, with the help of new research, with the doctrine which the Church holds and professes as regards to the Resurrection. As Romano Guardini, of happy memory, once noted in a penetrating meditation of faith, the gospel accounts underline “often and forcefully, that the Risen Christ is very different from what He was before Easter, and from the rest of men. His nature, according to the accounts, has some strange character. His approach confuses, fills with fear. Whereas previously He ‘came’ and ‘went’, now it is said that He ‘appears,’ ‘suddenly’ alongside the pilgrims, that He ‘disappears’ (cf. Mk. 16:9- 14; Lk. 24:31-36). No longer do corporeal barriers exist for Him. He is no longer bound by the frontiers of space and time; He moves with a new liberty, unknown upon the earth... But at the same time, it is strongly asserted that it is the same Jesus of Nazareth, in flesh and bone, just as He had lived formerly among his own, and not a mere phantom...” Yes, “the Lord is transformed. He lives differently than before. His present existence is incomprehensible to us. And yet, it is corporeal; it contains Jesus whole and entire, and even – by means of His wounds – all the life He has lived, the destiny He underwent, His Passion and His Death.” Thus, there is not simply a glorious survival of His “self.” We are in the presence of a profound and complex reality, of a new but fully human life: “The penetration and transformation of the whole life, including the body, by the presence of the Holy Spirit… We realize that change of perspective which is called faith, and which, instead of thinking of Christ in terms of the world, thinks of the world and of all things in terms of Christ... The Resurrection brings to flower a seed which He had always borne within Him.” Yes, we say again with Romano Guardini, “we need the Resurrection and the Transfiguration, in order to understand truly what the human body is... In reality, only Christianity has dared to place the body among the most hidden secrets of God” (R. Guardini, Le Seigneur, trad. R. P. Lorson, t. 2, Paris, Alsatia, 1945, p. 119-126).

In front of this mystery, we remain penetrated with admiration and full of wonderment, just as we feel before the mysteries of the Incarnation and the Virgin Birth (cf. Gregory the Great, Hom. 26 in Ev., Breviary reading on Low Sunday). Let us then enter, with the Apostles, into that faith in the Risen Christ which alone can bring us salvation (cf. Acts 4:12).

We are also full of confidence in the security of the tradition which the Church guarantees through her Magisterium – she who encourages scientific work at the same time as she proclaims the faith of the Apostles.

My dear Sirs, these few very simple words at the end of your scholarly labors, only wish to encourage you to persevere in the same faith, never losing sight of the service of the People of God, which is entirely “regenerated by the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, towards a living hope” (1 Pt. 1:3). And We, in the name of Him: “Who was dead, and has returned to life,” of that “faithful witness, the firstborn from among the dead” (Rev. 1:5; 2:8), We grant you, from a full heart and in pledge of abundant graces for the fruitfulness of your researches, Our Apostolic Blessing.

“Its end is the kingdom of God, which has been begun by God Himself on earth, and which is to be further extended until it is brought to perfection by Him at the end of time, when Christ, our life, shall appear, and creation itself will be delivered from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the sons of God.” (Lumen gentium, 9).

God’s entrance on the human scene, in Word and flesh, is history’s central event. Motivated by love, God responded to man’s condition, which required an extraordinary intervention, in order to re-establish order in creation. Above all, God’s Word and the theology of history facilitate the analysis of this situation. In their light, it is possible to practice a kind of lectio divina of humanity’s actions and to understand these actions from God’s perspective, not only for our own enlightenment but also for the enlightenment of others. This practice is essential, for we must know how to guide God’s people in interpreting the signs of the times, in the light of the Lord of time and history, who is history’s central figure and the source of all wisdom.

History is both God’s word and man´s word. But the words or actions of God are teachings that precede those of man, or responses to them; whereas man’s words or actions only may be in harmony or in disharmony with those of God. Human history is always the history of salvation and of the kingdom that underlies the human stories that we weave each day.

One of the characteristics of the history we are building is hastiness, which is due to an excessive acceleration and to a profound disorder. The world is spinning like a top out of control, “reeling from a wine” (cf. Ps. 60:5) that produces an unbridled haste. Meanwhile, this ‘time of the absurd,’ which places human actions outside the bounds and harmony of nature, breaks all moral norms and stifles any spiritual seeds of growth. This results in the ‘dead works’ of which the Scripture speaks (Heb. 6:1; James 2:17) and in a life that corresponds neither to the law nor to the meaning of life. For the warning has been forgotten, “in the day that you eat of [this tree] you shall die” (cf. Gen. 2:17).

«Despite this, we cast our nets once again, each one of us, each generation, with similar results. And each time we are told once again, “Don’t do things that way; that was not the right way; throw your nets in this new direction; throw them in a new way, in the way that I have taught you from the beginning; in other words, in the direction of Truth, of Freedom, and of Peace, which I am.” In fact, every human endeavor results in failure until we discover God standing on the shore.» “The Miraculous Draught of Fishes,” Raphael’s Tapestry. Vatican Museum.

«Despite this, we cast our nets once again, each one of us, each generation, with similar results. And each time we are told once again, “Don’t do things that way; that was not the right way; throw your nets in this new direction; throw them in a new way, in the way that I have taught you from the beginning; in other words, in the direction of Truth, of Freedom, and of Peace, which I am.” In fact, every human endeavor results in failure until we discover God standing on the shore.» “The Miraculous Draught of Fishes,” Raphael’s Tapestry. Vatican Museum.

Indeed, we have disposed of that which is most proper to man: the awareness of being made in the image of God, the presence of grace, holiness, truth, wisdom, beauty, honor, and the love of Christ, the Son of God and image of the perfect man, the Head of humanity. Rescuing this is the necessary condition for rediscovering our true human condition.

Within this context, we have erased the memory of the past or we have banished it as a time filled with shadows, but man’s turning his back on everything that has given life to past generations should create a great anguish, because today’s generation lives in a darkness far greater, despite all the glamour and scientific progress.

It is not man who establishes the measure of his own perfection or the meaning of natural law; in other words, the manner in which his physical and rational existence is ordered. We cannot recreate ourselves or our projects on a daily basis. We cannot deconstruct what God has created without us. We cannot prevent the Other, who is greater than us, from working in us. We may ignore or even disturb our human identity, but we cannot create in ourselves a novel and distinct identity, according to an image and likeness that has been imagined by us. Truth is not a question of will.

Reality stands on its own; it does not need anyone’s support. It belongs to every age and to every man, even when it is not accepted by anyone. However, man is seeking to establish a new law, for himself and for the world. It is the new utopia. Yet if man is God’s creation, this endeavor is futile. That is why we sometimes prefer to think of ourselves as a product of chance, for thus we may complete what has been left unfinished: forming man to realize his highest potential. We reach the point of believing that our word is worth more than God’s word, and that when all is said and done, we know more than He does. Thus, we allow ourselves to correct the divine works, words, and laws, and we substitute them with our own. We like our own ways better, and we believe that they are better suited to us. Indeed, we even fool ourselves into believing that God is not the measure of Truth, if He ever was. We have emptied the world of God’s presence and have filled it with all kinds of idols, and like in ancient times, we have said: These are your gods, O Israel!

We have built dreams and hopes that have not been realized upon these very convictions. In our own day, the most enticing of these dreams became the most devastating deception to aim at the masses: communism. In speaking of it, Benedict XVI wrote: “The idea was that we could turn stones into bread; instead our ‘aid’ has only given stones in place of bread.” (Jesus of Nazareth, p. 33)

Man loses the memory of himself when he loses the memory of God. Thus, he loses everything about himself. Despite that we may find in the present an unimaginable diversity of ideas about what man is, he cannot neither speak about himself nor identify himself in front of any reality: “These are waterless springs and mists driven by a storm” (2 Pet. 2:17).

The age of enlightenment has given way to the age of darkness, and the struggle of the Titans against God has caused an eclipse of the gods, and of man who has pseudo- divinized himself, pretending to supplant God. Therefore, despite the fact that the Truth has already been given in the Word, we find ourselves lost, wandering amid the present and future history of mankind, increasingly unable to deal with our history and to solve the enigmas that have developed over time. Therefore, “we have become like those over whom thou hast never ruled, like those who are not called by thy Name” (Is. 63:19). As in the original chaos, so also today the land is “empty and void” (Gen, 1:2), a desert to God and man.

Meanwhile, how do we justify the waste of time, of thought, and the squandering of energy that has occurred as a result of this work of destruction? Who will be responsible for the effects produced as a consequence of this confusion regarding the image of man and the moral ruin it has led to?

We cannot get too far when we recklessly run away from God. It would seem evident that not only the spiritual and moral aspects of society, but also the global condition of humankind, demand a fundamental transformation. It seems clear that the order of things needs to be re-established, that the primacy of Truth must be restored, that the world must be renewed, and that man must return to his true nature. This being said, it is important to note that this transformation is neither man’s intention, nor is it within his reach under the present circumstances. The deposit of beliefs and of primordial values that nourished humanity throughout its history is below the minimum, and we have entered into a condition of quiet madness which consists of considering as a fact that humanity has finally reached the utopia towards which it has been journeying.

In the light of God’s Word, we have to understand that what really matters is man’s realization in the Word in conformity with the divine will. For we know that God’s plan is to unite all things in Christ, the Head. (cf. Eph. 1:10). Consequently, God’s hour must come, not necessarily at the end of time, but now, in order to restore the reign of God’s will to this present hour, when the sin of paradise is being repeated: the decision to replace God’s design with man’s.

At the end of this long journey in darkness, we, like the apostles after their failed fishing attempt, find ourselves tired and empty after an exhausting effort. Despite this, we cast our nets once again, each one of us, each generation, with similar results. And each time we are told once again, “Don’t do things that way; that was not the right way; throw your nets in this new direction; throw them in a new way, in the way that I have taught you from the beginning; in other words, in the direction of Truth, of Freedom, and of Peace, which I am.” In fact, every human endeavor results in failure until we discover God standing on the shore.

To flee from God is to walk toward nothingness and the absurd. This is what happens when the attitude denounced by the prophet Jeremiah is repeated, “But they did not listen to me, nor did they pay attention. They walked in the stubbornness of their evil hearts and turned their backs, not their faces, to me.” (Jer. 7:24). Man will be restless until he is reconciled with himself; that is, until he rediscovers his true image, with its original destiny, as he received it from the Creator.

The Council warned us: “as deformed by sin, the shape of this world will pass away; (cf. 1 Cor. 7:31) but we are taught that God is preparing a new dwelling place and a new earth where justice will abide … we are warned that it profits a man nothing if he gain the whole world and lose himself (cf. Lk. 9:25)” (Gaudium et Spes 39 §1, §2). St. Peter tells us that “according to his promise we wait for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells.” (2 Pet. 3:13)

Each day, God sets out to meet man in order to respond to that hope, but He may also reach out to man in order to journey again with him through the desert, as He did with the Israelites, in order to lead him to the freedom and the inheritance that awaits him.

God will again tear to pieces the false images we have fashioned of Him and of ourselves. He will come again to fulfill what was once announced by Isaiah: “I will lead the blind in a way that they know not, in paths that they have not known, I will guide them. I will turn the darkness before them into light, the rough places into level ground” (42:16).

In fact, God is on his way: “Now I will arise,” says the Lord, “now I will lift myself up; now I will be exalted” (Is 33:10). “Be silent before the Lord God! For the day of the Lord is at hand; the Lord has prepared a sacrifice and consecrated his guests” (Zeph. 1:7; 1:14). For now, once again, it is the hour of the Lord, an hour with its own rhythm and laws: the call to conversion, the offering of mercy, warning and punishment according to what each man deserves; the gift of the New Pact.

This language, which speaks to us in such categorical terms about the renewal that stands on the horizon, and about the magnitude of the crisis, allows us to imagine that, in the face of man’s lack of control over life’s events, something new that goes beyond human intervention is still possible: “Listen to me, my people, and give ear to me, my nation; for a law will go forth from me, and my justice as a light to the peoples. My deliverance draws near speedily…, and my arms will rule the peoples; the coastlands wait for me, and for my arm they hope” (Is. 51:4-5). For “thus says the Lord, the Redeemer of Israel and his Holy One, to one deeply despised, abhorred by the nations, the servant of rulers: ‘Kings shall see and arise; princes, and they shall prostrate themselves…’” (Is. 49: 7ff.). “You are my son, today I have begotten you. Ask of me, and I will make the nations your heritage, and the ends of the earth your possession” (Ps. 2:7-8).

Certainly it seems that the most significant event that has occurred in the present age is the silence of God, who is allowing man to speak his word, and allowing him to freely express his powers, his knowledge, and his liberty. Yet the Ancient of Days riding in the clouds is preparing the way. His footsteps can be heard, and His footprints can be seen, but we need ears that hear and eyes that see.

We carry within ourselves the sometimes inconsistent expectations of a new coming, of a new world, of a new creation. The One who is coming tell us, “Behold, I make all things new” (Rev. 21:5). However, before “building and planting” it is necessary “to pluck, to destroy, and to smite” (cf. Sir. 49:7) much of what we have built, since these structures have not been built by the Father. “The day of the Lord is close at hand” (Is. 13:22). Or as we read in Hebrews “For yet a little while, and the coming one shall come and shall not tarry” (Heb. 10:37), in order that the Scriptures might be fulfilled. And again, elsewhere in Scripture it is written, “They shall look on him whom they have pierced” (Jn. 19:37).

God will again reveal His face to humanity, since he is the Head of the new humanity, the “Everlasting Father,” (Is. 9:6); for it is necessary that Christ return to dwell among us as the Light and Law of the world.

During Advent, the liturgy invites us to turn our gaze toward the One who comes, “Watching from afar I see the power of God advancing; let us go out to meet Him. Rise up, lift up your heads, your redemption is near at hand.” For behold, “I stand at the door and knock” (cf. Rev 3:20). To the “King who comes, to the Lord who draws near, come, let us adore Him.”

In the introduction to my speech* – which I entitled “Francis of Assisi, Sanctity for Times of Crisis” – I am going to talk about the discourse taking place at present on crisis. It is a fashionable discourse. There is talk of the financial crisis; of climate warming, which is a serious ecological crisis; and of the cultural crisis. Christian thinkers say, that basically, we are to a great extent in a situation of anthropological crisis, as there is opposition even to the very structure of the human body (the elemental structure of paternity) to the point that it is now possible to imagine factory production of the human being as a pure product, without defects, with a view to a perfection in the human market.

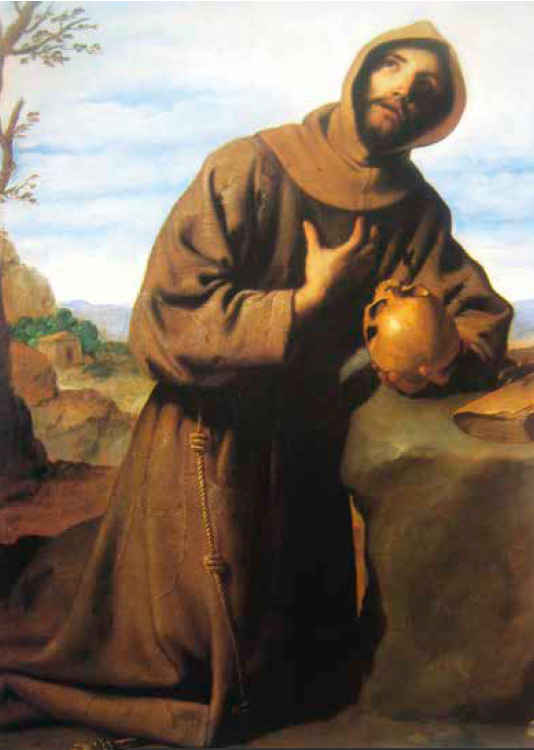

«He strips existence, taking away its dross and worldly plaques, to return to the source of being, to see one’s own existence spring from the bosom of God. It is through poverty that Francis resolves three great antinomies: between being and having, between fraternity and hierarchy, and between the cross and joy.» (Sculpture of Saint Francis by Pedro Mena. 1653, Cathedral of Toledo)

«He strips existence, taking away its dross and worldly plaques, to return to the source of being, to see one’s own existence spring from the bosom of God. It is through poverty that Francis resolves three great antinomies: between being and having, between fraternity and hierarchy, and between the cross and joy.» (Sculpture of Saint Francis by Pedro Mena. 1653, Cathedral of Toledo)

This discourse on crisis is quite peculiar for a Christian. Is it not a negative discourse on progress? Does it not correspond to the last sudden shock of a dying progressivism? If we believe that this crisis is an exception, this means that we still believe in a perfect society on earth or in progress that will lead us finally to an absolutely fraternal society. However, for its part, this is a discourse which has produced great totalitarianisms: the millennial Reich with a humanism limited to Aryans; Communism with the idea of producing an international, classless society; and Liberalism, which seeks to manage society by excluding ideology which, it believes, would make it possible to produce peace with the coexistence of individuals in a pluralist society. What we are left with, hence, is an horizon of progress where crisis appears to be something exceptional, from which it is necessary to emerge by retying together the broken ends. The problem, however, is that young people no longer believe in this. Our condition is always critical. The Church herself, through her proclamation, puts the world in crisis. When everything could be all right in an absolutely peaceable world, the discourse of the Church would generate a crisis in it and cause the unleashing of the forces of darkness. This is what occurs with Christ and his proclamation. It causes crisis because it impedes the world from shutting in on itself as totalitarianisms would have it and it obliges each one to decide, in advance, either for Paradise or hell. All individual life, no matter how small it is, is destined to this sort of absolute that leads it to a crisis, because it is, inevitably, a question of choosing eternal good or eternal doom.

In this respect, Francis was always radical. However, within this general crisis of history – since the fall and considering our redemption – I would like to point out a particularity of the present time. It is very important to consider the special moment in which we find ourselves, a moment described by a philosopher as “time of the end” (which is not the same as the end of times!). Why? The explanation is linked to three proper names which are the names of cities: Kolyma – Auschwitz – Hiroshima.

It is the end of all earthly hopes. It is the fall of progressivism and this… is marvelous! Because it shows that there is an urgency to re-found everything, not by resting on the world, but by depending upon God’s promises, namely, by re-founding everything on theological hope, which does not allow us to believe that the world will create the conditions of possibility, but that these are given to us by eternity. Hence, we can have confidence in the earth from what heaven gives us. And in this sense there is, contemporaneously, a real hope.

Perhaps the great danger today is fundamentalism. People will perceive, to such a great degree, the vanity of the world that they will try to escape to the beyond. When one is Christian, one knows that eternity is the cause of time, that eternity consists in seeing one’s neighbor and the whole of creation in God, so that eternity occurs here and now in a love that manifests itself on earth and in eternity (it is not a flight to the beyond).

It is here that Francis is our man!

What is the specific character of the Franciscan charisma? Does such a character exist or is Francis such an alter-Christus that he exceeds any specificity? I think there is a specificity. Francis is the Saint of crisis, not only because he enters the fire, converts wolves, and casts out the demons of Arezzo, but because he started from nothing and arrived … at nothing, which is even better!

It is said that God created from nothing. In Francis, when there is nothing, that is better. It is about having nothing in order to be better, to go to that nothingness from which God made himself Creator and re-Creator; to go to that nothingness where the creative power springs and springs again in us. Therein lies the specific Franciscan character: by the side of this sense of nothing from which springs the divine power and that Francis calls poverty. This is the most persistent call in Saint Francis and Saint Clare. In the Dominicans, it is to preach; in the Benedictines, the opus Dei, the liturgy; in the Cistercians, work and penance; in the Carmelites, prayer; in the Jesuits, the evangelization from the highest of society, but in the Franciscans it is poverty that occupies the first place.

In a letter to Brother Leo, Francis wrote: “To follow Christ’s footsteps and his poverty”. In an address transmitted to us by Saint Clare, he says: “I, little Brother Francis, want to follow the life and poverty of Our Lord Jesus Christ and his Most Holy Mother… and I beg you… to always live in this very holy life and in poverty…”

What poverty?

There is a danger in placing poverty as a banner, posing as being poor, boasting of a certain poverty. Francis abstained from denouncing the rich as evil. He was not about Liberation Theology nor was he a Marxist. In the second rule, he counsels the wearing of coarse habits… but also not to judge… and that each one judge himself and have contempt for himself

Francis is not a man about the personal development of a psychologizing type. It is not confidence in oneself that predominates in him, but resting in confidence in God, eventually in oneself, but through God, and not through one’s own natural strength. And it is in this that he espouses the crisis. By engaging in permanent interior criticism Francis leaps over paths, a highway bandit -; he comes to help us by stripping us (see in The Little Flowers, the doorman in “perfect joy”: he is right when he says that he robs the alms of the poor). Francis is not a humanitarian, he does not help the poor; he adopts poverty. If one is poor, he impoverishes one even more. Why? Because he knows that the Holy Spirit is the Father of the poor. He strips existence, taking away its dross and worldly plaques, to return to the source of being, to see one’s own existence spring from the bosom of God. It is through poverty that Francis resolves three great antinomies: between being and having, between fraternity and hierarchy, and between the cross and joy.

In Francis, the experience of money is fundamental. He is a bourgeois, son of the rising class that practices usury. Recall the three Giotto frescoes (the gift of the cape, the dream of the palace of arms, and the call of Christ of San Damiano), three comical scenes that are cruel at the same time, because in the face of God’s call in favor of his neighbor, given the urgency of the world, and in relation to the heart itself of the Church, Francis gives an answer that is good, but which is outside his vocation: he responds with money–it is an incorrect answer. Thanks to money, nobility no longer counts: the knight is no longer armed in nobility, but in the new hierarchy of money! His alms are ambiguous: is it revenge after having lost the war against the nobility of Perugia?

In fact, given the call “Be my soldier,” he buys arms! (fortunately, he soon falls ill). Then, when he hears “Repair my Church,” he does everything the wrong way round: he steals his father’s materials and his horse and offers his purse, always with the power of money. He realized that money could break the great traditional hierarchies; that money could become a means of a certain charity. Those answers are not in the evangelical radicalism of his vocation. In the long run, what would be the meaning of what Francis had done? In general terms, it would mean “to work more to give more”, which is always a temptation for Christian business leaders, who with difficulty return to their homes, and also pretend to no longer be able to observe Sunday because they have a target of alms that they must achieve: one must always give and hence one must always produce more… and the Shabbat came to an end. And Sunday rest came to an end! That is what money will demand: a logic in which one can give with money, enter into communication, a sort of equality through money, but in which one stays on the level of having, of production, and being is lost from view.

This logic has two limitations: on one hand, one remains in the order of having and on the other, one remains within the limit of giving and not of receiving. In my book “La foi des demons” (“The Faith of Demons) [Note of the editor: Cf. Humanitas 60, page 827], I explain that gift is what most attracts the devil, because he always wants to give, but from his own self, with his own strength, without having previously received by the grace of God. When one is a creature it is necessary, in the first place, to learn to receive; receptivity is fundamental. It is necessary to acknowledge that we are nothing by ourselves. We cannot give from our own self. (Saint John, chapter 8, says that the devil is a liar because he speaks of his own fund; he has forgotten the fundamental receptivity of the creature. He certainly knows better than us that nothing is by itself, but he would like to act with the minimum of communication with God and, consequently, especially without grace). If we want to give in the order of being, as we are not the first cause of being, we can only do so by having received previously from God. What we can give, believing that we are its first cause, is nothing. When it is a question of destroying, we are the first cause, we can do that alone. A logic of gift, which is disconnected from an initial receptivity, is a destructive logic. Man will want to transform everything with his own plans. And that is why he will decimate, put people in the Gulag or the gas chambers. Hence, Francis has nothing to give. In this he is faithful to the first mission of the Apostles after Pentecost: before the paralytic of the beautiful Door, Peter says: “I have nothing to give you… but in the name of Jesus…”

Francis teaches us a far more fundamental art than giving, he teaches us the art of receiving: to receive in mendicancy, in hospitality, in gratitude. He is a profoundly sabbatical man.

I am thinking here of that passage in The Little Flowers where Francis, in face of the crumbs he received, says that he is before a magnificent feast, and, on hearing this, Brother Leo replies: “But we mustn’t exaggerate!” It is important that there should be a Brother Leo; without him our Saint would seem like a sort of romantic who embellishes things. Francis’ answer is: “We have received it from the hand of God.” Pure Providence, and hence it is wonderful! Those crumbs are brought by eternity, enveloped in the tenderness of the infinite, so that it is something greater than the feast that we would have prepared with our own hands. It is the radical position of poverty to be more receptive to the gift of God. And precisely in this is an answer to the economic crisis.

Today we live in the logic of growth and consumption.

If poor people have acquired credits, it is because they believe in the paradise of consumption: there is the need to have a house, to obtain extremely dear credits. They did not come across Francis on their path, who would have told them that access to property is important, but it is necessary to be aware of illusion, as those people who offer credits will subject them to slavery.

«Saint Bonaventure said this in regard to Francis: “From so much going back to the first origin of all things, he conceived for all of them an overflowing friendship and he called creatures brothers and sisters, even the smallest, because he knew that he and they came from the same unique principle.”» (Oil painting by Francisco de Zurbaran)

«Saint Bonaventure said this in regard to Francis: “From so much going back to the first origin of all things, he conceived for all of them an overflowing friendship and he called creatures brothers and sisters, even the smallest, because he knew that he and they came from the same unique principle.”» (Oil painting by Francisco de Zurbaran)

He is, instead, in a logic of decrease, not related to the economic order. He simply says that it is not about increasing riches, but about receiving what is. The meaning of the Shabbat is blessed, because it is the day in which man does not work, as it is the day in which he harvests. One can produce interminably to the point of not knowing how to use things, the small things. Poverty teaches us how to use things, to marvel at small things. Because of this, for Franciscans to be a prophetic sign today is to be faithful to their rule of poverty. Having said this, we must also say that ownership is proper to man. Animals do not have. Man produces and has. Francis is aware of this. However, one can also become a prophetic sign in this sense –the poverty of having can make one enter into the richness of being and that someone can tear people away from the madness of having increasingly more and more, to enter increasingly into being. The vocation to the strict observance of the Minor Brothers is not the same as that of their spiritual friends who must know how to use money. There is a difference between the vocation of the Religious and that of the layman. The Franciscans were the first to write treatises on the subject of loans, to emerge from the logic of usury, who wanted money to circulate in better distribution, but they themselves must not enter into that logic. They are foreign to it; they are, rather, the men who give up money and property to be in the nakedness of being.

At the end of the battle of Perugia, in which the nobility was expelled from Assisi, a pact was signed with the bourgeoisie of the city so that they would have some power in its governance. The word “minores” appears and describes the bourgeoisie, the nobles being entitled the “maiores.” The bourgeoisie are the minor citizens. Francis founded the Minor Brothers.

He realized that money makes possible that sort of leveling, it creates new inequalities and is, in addition, something extremely dangerous, as it bestows power, but the most ephemeral of powers. Someone becomes very rich and then everything collapses, yet he remains bound by the fascination for money. When the ecclesiastical hierarchy tended towards a worldly hierarchy and turned to money, as it acquired greater power, it was weakened. Francis perceived this fragility, reinforced by the logic of money. That is why he did not think of leveling the realm of having, as a Marxist would, but of a fraternity of being. Fraternity is to possess a sense of divine paternity. There is no fraternity without a father. It is necessary not to fall into the “republican” logic of fraternity, which would like us to be a fraternity without a father. Moreover, that does not work. One does not understand well what that “republican” fraternity in France’s motto is. Liberty, yes, equality, yes, but fraternity as it is understood today (without paternity), would be equivalent, rather, to laicity. Saint Bonaventure said this in regard to Francis: “From so much going back to the first origin of all things, he conceived for all of them an overflowing friendship and he called creatures brothers and sisters, even the smallest, because he knew that he and they came from the same unique principle.”

Francis is not a humanist in the strict sense of the term. The fraternity of which he speaks is a fraternity with all creatures. And he would go beyond the “deep ecology” that speaks of fraternity with animals and plants: for him it is also “my brother fire,” “my brother wind” and also “our sister death.” The radicalism of Franciscan fraternity is unique precisely because it understands that our being is received from God in the same way as any other creature and in that radical poverty of the creature. However, Francis will also not be in that shapeless fraternity. If our fraternity is constituted from our mother, the earth, the shapeless matter, then everything is the same and we would enter into the logic of the “deep ecology” of Peter Singer (Movement for Animal Liberation), which again creates a hierarchy from utility and holds, for example, that a good cow is more useful than a handicapped person, who cannot do anything and only digs a hole in social security. For Singer, such a cow would have a dignity that is superior to that of the useless person. Thus, in this perspective, that cow would also be superior to Francis of Assisi, who wished voluntarily to be a disabled person, a poor man among the poor, and to beg. Instead, as fraternity comes from the Father who orders all things, there will be an order, and fraternity will not oppose hierarchy, but will be rethought in greater depth in the hierarchy of beings.

When Thomas Aquinas asks if God loves all creatures equally, he returns to Aristotle’s definition and says: “To love is to will the good for someone, and the more or the less can be given whether it is in the realm of loving (with greater or lesser intensity), or in the realm of the good granted (a good of greater or lesser extent).” To which Thomas adds that there is inequality in the goods that God gives, but that this does not mean that each one is not fulfilled, but that each one is fulfilled in a different degree from another. Consequently, the good communicated is unequal. However, Thomas then adds something of which Francis possessed a profound intuition. That in God’s loving, there is only one act of will; it is one and the same infinite love, which is very amazing. There is equality in infinite love, in its intensity, but there is inequality in as much as each one is given what he can and must receive. That is why we really exist in a sense which is neither economic nor ecological, but in a creaturely sense, which is ordered and hierarchical, as each one is given according to his needs. This is fundamental. This is also true for the relations within the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Often there has been an attempt to present Francis’ universal fraternity in conflict with the papacy. Respect for priests and especially for the Pope is fundamental in Francis because he knows that degrees of hierarchy represent degrees of sanctity. In the Church there is a hierarchy, not of power but of service. The Pope is the servant of the servants of God; consequently Francis shows that this hierarchy is ordered towards universal fraternity and is not a proletarian fraternity, subjected to a hierarchy of power. It is about the grandeur of a very lofty poverty, receptive of God, and is heart of sanctity.

Fabrice Hadjadj was born in Nanterre in 1971 of parents of Jewish origin and Maoist ideology. He spent his childhood in Tunisia and France. At present he resides in French Provence, where he is a professor of Philosophy and Literature. He is a regular contributor to Le Figaro newspaper of Paris. Having converted to Catholicism in 1998, he sometimes introduces himself as “a Jew of Arab name and Catholic confession”. He is an essayist and playwright. He is married to actress Siffreine Michel, by whom he has five children. At present he teaches in the Sainte-Jeanne D’Arc private institute and in the Seminary of Toulon. The present text corresponds to a literal, translated, edited and revised transcription by its author, of an address given in the assembly of the Order of Saint Francis held at Lourdes, France on the 8th centenary of the Order. During the opening of his address Hadjadj pointed out: “In the first place, I would like to say that I am a perfect ignoramus; I have no Totum where I live. However, it is the Franciscan tradition to receive the poor, so I introduce myself to you as a poor man, as a person without any authority on the subject. “It will be a personal focus and my treatment will be doubly external, given that I belong rather to the Benedictine family (I am an oblate of Solesmes) and, in addition, I am of the Thomistic theological tradition, hence rather on the Dominican side. In any case, neither the figure of Saint Benedict nor the figure of Saint Dominic has marked me as much as that of Saint Francis. As you see, Saint Francis always had a radiation beyond his Order. It is one of his great particularities.”

Fabrice Hadjadj was born in Nanterre in 1971 of parents of Jewish origin and Maoist ideology. He spent his childhood in Tunisia and France. At present he resides in French Provence, where he is a professor of Philosophy and Literature. He is a regular contributor to Le Figaro newspaper of Paris. Having converted to Catholicism in 1998, he sometimes introduces himself as “a Jew of Arab name and Catholic confession”. He is an essayist and playwright. He is married to actress Siffreine Michel, by whom he has five children. At present he teaches in the Sainte-Jeanne D’Arc private institute and in the Seminary of Toulon. The present text corresponds to a literal, translated, edited and revised transcription by its author, of an address given in the assembly of the Order of Saint Francis held at Lourdes, France on the 8th centenary of the Order. During the opening of his address Hadjadj pointed out: “In the first place, I would like to say that I am a perfect ignoramus; I have no Totum where I live. However, it is the Franciscan tradition to receive the poor, so I introduce myself to you as a poor man, as a person without any authority on the subject. “It will be a personal focus and my treatment will be doubly external, given that I belong rather to the Benedictine family (I am an oblate of Solesmes) and, in addition, I am of the Thomistic theological tradition, hence rather on the Dominican side. In any case, neither the figure of Saint Benedict nor the figure of Saint Dominic has marked me as much as that of Saint Francis. As you see, Saint Francis always had a radiation beyond his Order. It is one of his great particularities.”

Francis was the first stigmatic in history. What the first Brothers would see in him, was the stigmatic, and not the Francis, the brother of creatures and very fashionable today, but instead the second crucified one. This is fundamental in avoiding a romanticism or forgetfulness of the drama of history. Fraternity is not only a fact but something that also happens through the cross. It is given, but also through sufferings, because we are sinners and we must be converted. Francis is often harsh, because he knows that he is speaking of a fraternity in God and that what is against God must be thrown into the fire and disappear. Therefore, he can make use of a tremendous force in fraternal correction. It is not about “our smiling, our being together in a mutual complacency, well accommodated in warmth while the evil ones are outside.” No, rather we are going to go before the evil ones because we know that without the grace of God we would have been worse than them. The cross is both the work of injustice as well as the work of joy (Cf. The Little Flowers, chapter “Perfect Joy”). It is joy that calls primarily for the cross in the present condition of the world, because joy, happiness, is received from God so that it crucifies our pride. Francis speaks about overcoming oneself. Consequently, in the first place is the suffering of pride, of the creature that is closed and must be torn, whose shell must be broken to receive divine light and hence true joy, separating himself from all petty pleasures. In the second place, not only is joy received, but it wants to communicate itself. What would a joy be that is kept to oneself in a narrow and egotistical manner? There is no better definition of hell than that of a small pleasure turned in on oneself. Then it is necessary to suffer to transmit joy. It is joy that goes searching for the cross. There is no duality. Hence, Francis the crucified, is the same as the joyful Francis, because it is this crucified one who receives the joy of God and communicates it to his brothers entering into their affliction, identifying himself with their affliction.

Helping the poor is not what he does, because as such it would only be a social work, of the world, as do others that are very good. It is essentially about becoming one with the poor. Christ willed to save us by becoming one of us. The Franciscan goes before the poor man, making himself poor. Here is a profound answer to the anthropological crisis, because if man destroys himself it is because he wants to save himself, to be the author of his joy rather than receiving it from God and all the other creatures from a fundamental poverty. Francis calls us again to this receptivity and he calls to it in praise, a poor word par excellence and also hospitable. When I praise God, I tell Him that I do not praise Him yet or that I praise Him insufficiently. It is a wounded, poor word. It calls all other creatures: “Praise the Lord with me,” to be able to approach God with praise worthy of Him. And in addition it calls to the future. Praise is always ecclesial, but in addition it appeals to the end of time. “I will sing to the Lord.” It receives the coming eternity. For that reason also, in this radical entrance into the mystery of poverty, Francis opens us to the loftiest praise.

Translated by Virginia Forrester.

When the fresco of the Last Judgment was first unveiled in the Sistine Chapel, Paul III fell to his knees in an act of humble reverence, fearful before the majestic figure of

New Book: “The Pope Benedict XVI Reader”

07 May 2021Newman’s Rhetorical Strategies in Idea of a University

14 January 2019Passion for man

04 December 2018On Forgiveness

04 December 2018