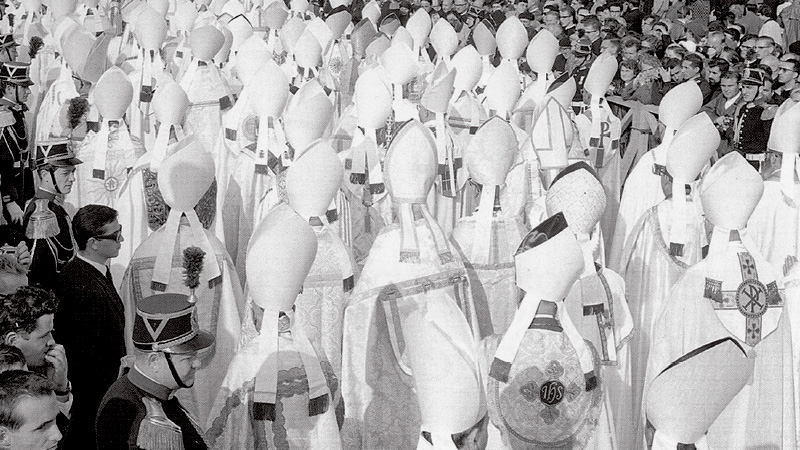

A few weeks before Vatican Council II, Cardinal Siri invited Cardinal Frings, Archbishop of Cologne, to Genoa for a conference on the Church in the modern world. The elderly German Cardinal asked for help from a young teacher and theologian whom he trusted: Joseph Ratzinger, who wrote the text for the conference. John XXIII was so impressed that during an audience he embraced Cardinal Joseph Frings and said to him: “Those where precisely my intentions for calling the Council.” On the occasion of the indiction of the Year of Faith and of the celebration of the anniversary of the Vatican Council II, the following pages present a summary of that enlightening text that exposed with surprising clarity the profound transformations that occurred after Vatican Council I (1869-1870) and that were the source for the need of calling the new Council.

Introduction

The text of the following lecture, composed by J. Ratzinger but delivered by Cardinal Josef Frings, in Genoa, November 20, 1961, was published as “Kardinal Frings über das Konzil und die modern Gedankenwel”» [Cardinal Frings on the Council and the Modern World of Thought] in Herder-Korrespondenz 16 (1961/62) 168- 174. It also appeared in other venues in the original German and translated in French. The Italian translation for delivery in Genoa also appeared in a book containing this and other lectures in the series in which it was given.1

Two Preliminary Considerations

1. The Council and the Present Age

Councils always express God’s word in a way influenced by contemporary circumstances which make it imperative to give Christian doctrine a new formulation.

Councils use the thought of their own age with the aim of taking the self-willed minds of their contemporaries captive for Christ (cf. 2 Cor. 10:5) and to deal with the Church in her spiritual growth toward “the full stature of Christ” (Eph. 4:13).

For the success of the coming Council, with its aim of aggiornamento (Pope John XXIII), it is especially important to examine the cultural and intellectual world of today, in the midst of which the Council intends to place the Gospel not under bushel basket but on a lamp-stand, so that it may enlighten everyone living in the house of the present age (cf. Mt 5:15).

2. Changes in the Cultural and Intellectual Situation since Vatican Council I

Vatican I met [1869-70] when liberalism was dominating politics and economic life, while also making initial inroads into theology through historicism, which soon led to the Modernist crisis in Catholic theology as the 20th century began.

Before Vatican I, after the seismic shocks of the Enlightenment, a theological rebirth had begun, along with the indispensable growth of sound philosophy. But a seething uncertainty, common to new beginnings, marked Catholic thought, as it swung between the extremes of rationalism and fideism in trying to ward off the attacks of liberalism. Also Feuerbach and Haeckel were making initial proposals of materialism.

One might think our situation resembles that of Vatican I, but major changes have taken place in the Church’s relation to the world around it. In a now united Italy, the Church is a far different since the end of the Papal States. France has experienced the triumph of a laicizing secularism and the German monarchy collapsed [in 1918], while secularizing governments in Latin America have expelled the Church from influence on public life.

The two World Wars set us at a distance from Vatican I. World War I brought the end of one type of liberalism with its proud confidence [in promoting human progress]. Catholic life was finding new vigor [in the 1920s], while two powerful movements filled voids left by discredited liberalism, namely, materialistic Marxism in Russia and romantic nationalism in Italy and Germany, leading to the horrors of World War II. With the evil abyss of these movements unmasked, liberalism is surging anew and making some aspects of our situation seem similar to that of Vatican I.

But the past does not simply return, whatever may be the connections between the present and what was present in embryo in 1869-70. Our age is truly different, and so we will try to characterize the basic currents of present-day culture and thought which affect the task incumbent upon the teaching work of the coming Council

The Church and Modern Thinking: The Spiritual-Intellectual Condition of Humanity on the Eve of the Council

1. The experience of the Human Race as One

Perhaps the most notable experience marking our present situation is how the world has shrunk and humanity senses its oneness. Radio and TV bring the whole world into every home and in large cities we meet persons from all over the world.

Covering over the special aspects of particular cultures, a unified technical culture influences our lives and gives all people the common categories of the European-American technological civilization, a situation comparable to the common Hellenistic culture around the Mediterranean in Jesus’ time.

This is a kairos for the church, a divine call to look to all human beings. “It has to become in a fuller sense than heretofore a world Church.”2 The process has begun in mission lands with the erection of indigenous hierarchies, but further steps must follow.

When Christianity first spread, it did not hesitate to embrace the koinē Greek of the day and proclaim the Gospel in the terms, and even the Stoic immanentist categories, of that language. Today another koinē is at hand, namely, the terms and categories of a technological civilization.

Regarding the missionary problem, we speak much of accommodation, by which the content of faith becomes assimilated to different national cultures […]. One can ask whether it is not at least just as urgent to look for a new form of proclamation which take captive for Jesus Christ the thinking of today´s unified technological culture and so transform humanity’s new koinē into a Christian dialect.3

One might see the dominance of this new civilization as a victory of European customs. But the experience of two world wars has revealed the dark and violent side of European culture, leaving other peoples skeptical about Christianity and its potential for changing the world. Asians take note of the Christian history bloodshed and persecution and ask themselves whether the patient genius of India or the abstaining and forgiving smile of the Buddha does not offer a more credible promise of peace than does Christianity.

Paradoxically, the victory of technology has been accompanied by a limited rebirth of other cultural currents, as we see in revived study of the Qur’an among Arabs and the attraction of Westerners to Hinduism and Buddhism. This affects the self-understanding of Christians who were inclined to attribute a certain absolute value to the western heritage.

The emergence of new worldwide perspectives has left Westerners disillusioned and aware of the limited significance of their own culture and history. This takes away one of the most important external supports for faith in the absolute character of Christianity and it exposes Westerners to a relativism that is probably one of the most characteristic elements of today’s intellectual life, an outlook present in believers too. But it would be mistaken to believe that relativism is completely bad. If it leads us to recognize the relativity of all human cultural forms and so inculcates a humility which sets no human and historical heritage as absolute, then relativism can serve to promote a new understanding between human beings and open up frontiers previously closed. If it helps us recognize the relativity and mutability of merely human forms and institutions, then it can contribute to setting free what is really absolute from its only apparently absolute casing and so let us see this really absolute more clearly in its true purity. Only when relativism denies all absolutes and admits only relativities, is it then a certain denial of faith.4

Amid this new concern for the special values of particular peoples outside Europe, the Church has the task of inculcating the unity of faith and worship as it carries out its vocation of creating peace across all frontiers.

The situation calls the Council to an examination of conscience with a view to opening the Church more than before to the varieties of human culture, which is proper to the Catholica. As the truly spiritual people born of the Spirit and water (Jn. 3:5), it has to remain open to the variety of humankind and “within the higher framework of unity it has to realize the law of diversity.”5 This has consequences, in order to make Catholicism more catholic:

– Not all laws are valid in the same degree in every country.

– While liturgical worship should be a sign of unity, it must also be an appropriate expression of given cultural specificity, if it is to be a peoples’ spiritual worship of God (Rom. 12:1).

– Local Episcopal authority has to be naturally strengthened in order to meet the needs of particular churches, while keeping bishops together in unity with the whole episcopate around its stable center, the Chair of Peter.

2. The Impact of Technology

The new technological culture affects human beings religiously in a manner different from that of previous cultures. Earlier human beings had many direct encounters with nature, but the world we now encounter bears the mark of human work and organization.

Historically, direct encounters with the natural world were important starting points for religious experience, since God is to be known through the things he has made (Rom. 1:20). But now we lack this significant source of religious experience, as shown by the decline of faith among modern industrial workers.

But we should not demonize technology, since God gave the earth over to human beings to till and subdue (Gen. 2:15, 1:28). In fact, every human situation has its own potential and dangers, and fallen human beings even worshiped God’s natural creatures. But technology can lead to the worship of the human itself.

Now the world has become irreversibly profane and human beings appear worthy of homage in bringing about progress. In this new situation religion has to interpret and justify itself in new ways. To indicate the way ahead, we have to introduce a further consideration.

3. The Credibility of Science

Masses of people now have high expectations of science, even for solutions to deep human needs, e.g., for norms of practice from social research like the Kinsey-Report,6 or for healing from therapy based on psychological insights. Many hope to evade ethical struggles.

But here is the point at which the meaning of faith can be shown to those of the technological era.

The human person remains “the unknown” entity (A. Carrel)7 or “the great abyss” (Augustine),8 about whom, to be sure, today’s scientific methods explain much, but in whom, an unexplained and inexplicable remainder always lies beyond sociology, psychology, pedagogical research, and whatever else. This remainder is basic, in fact decisive, for it is what is properly human. Love remains the great miracle outside all calculation. Guilt remains the dark possibility that statistics can never discuss away. In the depth of the human heart, a solitude remains which cries out for the infinite and finds ultimate satisfaction in nothing else. It remains true solo Dios basta [God alone suffices].9 Only the infinite suffices for the human being, whose true measure is nothing less than the infinite.

Can it be impossible to make technological humans aware of this? While they no longer have nature to speak to them of God, they still have themselves and their hearts which cry out for God. This is the case even when they no longer understand the language that springs from solitude and need interpreters to lay open its meaning.10

In this technological age, religion will be more sparse in content, but perhaps deeper. To give persons the help they expect, the Church may well leave behind older outward forms, to allow what are properly matters of faith to appear more clearly as being of lasting value.

The Church must show itself fearless before science, since she is secure in God´s truth, which no true progress can contradict. The Church’s certainty, underlying its freedom and composure, can well point our contemporaries towards that unconquerable faith that the world cannot overcome because such faith contains the force that overcomes the word (1 Jn. 5:4).

4. Ideologies

So far, no mention has been made of Marxism, existentialism, and neo-liberalism, the ideologies born from a world made profane to replace faith as an account of the world and source of the meaning of life, which they offer, but without referring to a transcendental Other. Ideology springs from the human person thrown back upon himself and hesitant to make the wager of faith, but still producing what religion once gave.

Actually wide swaths of European, American, and Russian populations have been “un-ideologized” and live in a pragmatic but shrunken worldview no longer promising earthly paradise but only serving to support consumerism and comfort. But this is no lasting answer to the human quest.

Here the Church has its positive task, namely, to show that that Christian faith is the true answer to the human quest for meaning. It has to make perceptible what appeals to individuals in ideologies, such as a hope that saves from despair. This rests on a promise made not only for the individual, but for humanity, the earth, and the whole world.

Nineteenth century Christianity went too far in concentrating on individual salvation in eternity, while neglecting Christianity’s universal hope for the whole of creation destined for salvation, since Christ is Lord of all things.

Christianity has the task of thinking through anew, and meeting modern people’s ardor for the earth, with a fresh interpretation on the world as creation giving witness to the glory of God and as a whole destined for salvation in Christ. He is not only head of his church, but Lord as well of creation (Eph. 1:22; Col. 2:10; Phil. 2:9f).11

Liberalism promotes true values, such as a tolerant respect for the spiritual freedom of others and an unconditional drive for honesty over and against slogans. Christians can well embrace these outlooks, which ground opposition to totalitarian claims. The Church, in the Council, should undertake a full and critical review of its own practice, like the Index of Forbidden Books, which resemble totalitarian restriction on the quest for truth.

The Hole Father has spoken of the coming Council as especially a reform council dealing with practical matters. In re-examining old forms, the Council will find a series of tasks which may seem concerned with externals, even with small points. But if this is carried out, such action, more than many words, will make the Church more accessible for the people of today as the Father’s house in which they can dwell joyfully and secure.12

Concluding Thoughts

So far we have spoken of the world outside the Church, not taking account of the Church’s modern condition, to which the last half-century has brought benefits unthinkable at the time of Vatican I. Charismatic gifs of God’s Spirit abound for the vitality of the Church and they have taken their place alongside the order created by regular Church government.

Two broad movements have arisen and been officially recognized as relevant for the whole Church, namely, the Marian movement spurred on by Lourdes and Fatima, and the liturgical movement beginning in French, Belgian, and German Benedictine monasteries. The latter has led many to discover the Bible afresh, along with the Church Fathers, and this has created conditions for dialogue with separated Christians and most recently led to the creation of the new Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity.

But the two movements, with their characteristic impulses, are strangely alien to each other. Liturgical piety can be called “objective and sacramental,” while Marian piety is “subjective and personal.” In liturgy one moves “through Christ to the Father,” while Marian devotion goes “to Jesus through Mary.” Although both are present everywhere, the Marian movement flourishes in Italy and lands where Spanish and Portuguese are spoken, while the liturgical movement is strong in France and Germany.

This shows, first, that diversity enriches, as people bring their own gifts into the unity of the body of Christ. We cannot yet imagine the new riches to come when the charisms of Asia and Africa make their contributions to the whole Church.

A glimmer of the unity of the two movements begins to emerge with the insight that Mary does not stand alone, but is the icon and image of mater ecclesia [Mother Church]. She shows that Christian devotion does not leave individuals alone before God, but takes them into the community of the saints, where Mary is central as our Lord’s mother. She shows that Christ will not remain alone, but intends to form believers into one Body with himself, to have “the whole Christ, head and members” (St. Augustine).

This community comes together in liturgical prayer and the liturgical movement should in the coming decades seeks to integrate Marian piety, with its warmth, personal commitment, and readiness to do penance, while promoting among Mary’s devotees a holy sobriety and the disciplined clarity of early Christian norms of prayer and worship.13

Finally, there is the witness of suffering and martyrdom, which has marked the past half-century even more widely than in the first three centuries of Roman persecution. This gives us good reason not to bewail our spiritual situation as tired and impoverished, for the power of the Holy Spirit is not absent amid such signs of victorious life.

The Council must serve this vitality of the Church, promoting the witness of Christian life more than issuing doctrines. This will show the world what is truly central, namely, that Christ is not merely “«Christ yesterday,” but is the one Christ “yesterday, today, and forever” (Heb. 13:8).

The Council must serve this vitality of the Church, promoting the witness of Christian life more than issuing doctrines. This will show the world what is truly central, namely, that Christ is not merely “«Christ yesterday,” but is the one Christ “yesterday, today, and forever”

The Council must serve this vitality of the Church, promoting the witness of Christian life more than issuing doctrines. This will show the world what is truly central, namely, that Christ is not merely “«Christ yesterday,” but is the one Christ “yesterday, today, and forever”