Theodosius Dobzhansky, the great researcher and thinker who made fundamental contributions to the subject of evolution, stated: “Undoubtedly, the human mind clearly separates our species from non-human animals. […] Human self-consciousness obviously differs greatly from every rudiment of mind that may be present in non-human animals. The magnitude of the difference makes it a difference in kind, not in degree. Because of this primary difference, mankind became an extraordinary and unique product of biological evolution.”1

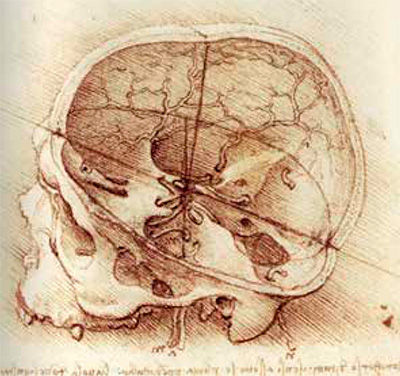

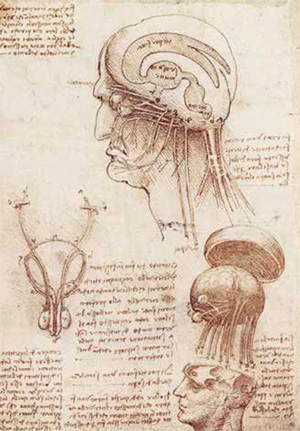

«Stoeger, in a concise philosophical analysis on the mind-brain problem, observes: “We know that matter is necessary for the mental and spiritual we experience, but we also know that what we understand and know about neurologically organized matter is not sufficient for explaining the manifestations of the ‘mental’ or ‘the spiritual.’» (Study by Leonardo da Vinci)This reliable and indisputable statement definitively confirmed the truth of the Homo sapiens. Man, of whom it may certainly be said that a particular aspect deserves serious attention: the relationship between brain and mind. In a careful study on the architecture of the brain, L. W. Swanson stated: “The cerebral cortex is the crowning glory of evolution. It is the part of the nervous system that is responsible for thinking. […] It is the organ of thought.” Further on, after having observed that “the actual dynamics of information processing within the network of connections between the various cortical areas is far from understood,” he concluded: “The cerebral hemispheres appear to form an integrated unity – which from the functional perspective is responsible for elaborating cognition and for transmitting cognitive influences to the motor, sensory, and behavioral state systems.”2 However, W. R. Stoeger, in the introduction to a comprehensive work on the mind-brain problem, rightly noted: “At least at our level of understanding of the brain and its processes – extensive and detailed as it is – we do not yet know how mind and brain are related.”3 In reality, the adult human brain – weighing around 1,300 grams, composed of approximately 100 billion neurons, 30 billion of which are found in the cerebral cortex, and numbering as many as 100,000 different kinds,4 each contributing to different aspects of mental life5 – does not think, but readies, as N. Chomsky emphasizes, “the physical realization of mental life.”6 The architecture and activity of the neo-cortex is essential to this process. Its functions in the human subject include: the execution of motor skills, the expression of emotion, the use of words and an active mental development proper to the human species. It is an extraordinary instrument composed of parts that are formed, developed and arranged in accord with a plan written into the DNA proper to each individual that is gradually realized through the subject’s growth and development. It is a highly perfected organ, essential to the human person, which receives, records, and stores. But W. R. Stoeger, in a concise philosophical analysis on the mindbrain problem, observes: “We know that matter is necessary for the mental and spiritual we experience, but we also know that what we understand and know about neurologically organized matter is not sufficient for explaining the manifestations of the ‘mental’ or ‘the spiritual.’”7 Careful reflection clearly shows the presence of an energy of the mind, formed by two forces that are not material but spiritual. Rightly, then, did G. M. Streeter state: “The brain is not the mind. The brain is the mind’s physiological infrastructure. […]. [We] have, perhaps for the first time, a modest beginning account of what empirical functions belong properly to the human spirit, as we have had from science the continually unfolding discovery of the functions of the brain.”8

«Stoeger, in a concise philosophical analysis on the mind-brain problem, observes: “We know that matter is necessary for the mental and spiritual we experience, but we also know that what we understand and know about neurologically organized matter is not sufficient for explaining the manifestations of the ‘mental’ or ‘the spiritual.’» (Study by Leonardo da Vinci)This reliable and indisputable statement definitively confirmed the truth of the Homo sapiens. Man, of whom it may certainly be said that a particular aspect deserves serious attention: the relationship between brain and mind. In a careful study on the architecture of the brain, L. W. Swanson stated: “The cerebral cortex is the crowning glory of evolution. It is the part of the nervous system that is responsible for thinking. […] It is the organ of thought.” Further on, after having observed that “the actual dynamics of information processing within the network of connections between the various cortical areas is far from understood,” he concluded: “The cerebral hemispheres appear to form an integrated unity – which from the functional perspective is responsible for elaborating cognition and for transmitting cognitive influences to the motor, sensory, and behavioral state systems.”2 However, W. R. Stoeger, in the introduction to a comprehensive work on the mind-brain problem, rightly noted: “At least at our level of understanding of the brain and its processes – extensive and detailed as it is – we do not yet know how mind and brain are related.”3 In reality, the adult human brain – weighing around 1,300 grams, composed of approximately 100 billion neurons, 30 billion of which are found in the cerebral cortex, and numbering as many as 100,000 different kinds,4 each contributing to different aspects of mental life5 – does not think, but readies, as N. Chomsky emphasizes, “the physical realization of mental life.”6 The architecture and activity of the neo-cortex is essential to this process. Its functions in the human subject include: the execution of motor skills, the expression of emotion, the use of words and an active mental development proper to the human species. It is an extraordinary instrument composed of parts that are formed, developed and arranged in accord with a plan written into the DNA proper to each individual that is gradually realized through the subject’s growth and development. It is a highly perfected organ, essential to the human person, which receives, records, and stores. But W. R. Stoeger, in a concise philosophical analysis on the mindbrain problem, observes: “We know that matter is necessary for the mental and spiritual we experience, but we also know that what we understand and know about neurologically organized matter is not sufficient for explaining the manifestations of the ‘mental’ or ‘the spiritual.’”7 Careful reflection clearly shows the presence of an energy of the mind, formed by two forces that are not material but spiritual. Rightly, then, did G. M. Streeter state: “The brain is not the mind. The brain is the mind’s physiological infrastructure. […]. [We] have, perhaps for the first time, a modest beginning account of what empirical functions belong properly to the human spirit, as we have had from science the continually unfolding discovery of the functions of the brain.”8

The mysterious emergence of the word in the human species is truly an extraordinary event: it is the means by which thought that is elaborated by the mind through an intense and ordered cerebral activity is communicated. Mind and consciousness are the two essential, characteristic features that clearly separate the Homo sapiens from all the rest of the animal world. Mind, an energy that thinks, reflects and expresses itself through language that is understandable, highly developed and extraordinarily driven by the activity of billions of neurons that operate in an orderly manner without interruption in the brain. Consciousness, a power of reflection that examines what the mind expresses, in order to judge its value: good or evil. “Faced with the revelation of the structures of the human brain, which develop gradually as an indispensable instrument that enables the human person to elaborate and express the fruit of his mind, and to choose and execute his own decisions, we cannot but perceive the enjoyment of a privilege particularly reserved to the species Homo sapiens.”9

Splendor and shadows of the human brain

The essential framework of an adult human brain is the critical structure for the apprehension and formation of memory. It is a veritable “jungle” of approximately 100,000 kinds of neurons, each contributing to a different aspect of mental life10 nourished by a thick network of blood capillaries through which it receives oxygen and glucose in a rigorously controlled flow. However, it is a jungle that is clearly structured into the so-called three-dimensional topological organizations. The principal one among them is the cerebral cortex: an intricately involved, thin sheet of about 1,000 cm2, 35 cm in diameter and 2-3 mm thick, consisting of six layers of cells, each of which sends and receives specific signals, with a density of approximately 100,000 cells per mm2. This is the most important population; but others of no lesser importance are also present, each with its own proper characteristics and tasks. Today, through more refined instruments, it is a jungle that is more widely travelled and explored. The cognitive system deserves particular exploration and study. With evident satisfaction, but also with a certain concern, L. W. Swanson in his careful study on the architecture of the brain states: “The cerebral cortex is the organ of thought. Can the organ of thought ever understand itself? Will we ever understand the physical basis of thought? […] What is the biology of consciousness? If nothing else – how far have we come in our attempts to understand the brain substrates of thinking?”11

Today it is believed that man’s cerebral cortex, called the isocortex, is formed by six layers of neurons, divided into three super layers: 1) the supragranular layers, which generate the immensely complex network of connections between the three cortical areas, probably responsible for thinking, learning, and memory; 2) the infragranular layers, which are essentially the “motor” part of the cerebral cortex; 3) the descending projections of the pyramidal neurons in the infragranual layers. Given their complexity, W. Swanson rightly observed: “the actual dynamics of information processing within the network of connections between the various cortical areas is far from understood”; but he concluded: “The cerebral hemispheres appear to form an integrated unity – which from the functional perspective is responsible for elaborating cognition and for transmitting cognitive influences to the motor, sensory, and behavioral state systems.” Three observations merit particular attention. The first, initially made in an extensive study of D. Albright and his colleagues,12 demonstrates that we are still far from an in-depth knowledge of the state of neuro-psychic mental activities and from other similar considerations, which underscores the need for a serious study of many aspects of the human mind that are still problematic. The second, offered in a recent work by L. Cahill,13 who put forth a synthetic analysis of the brain of the two sexes over the last decade, concluded by stating: “The existence of widespread anatomical disparities between men and women suggests that sex does influence how the human brain works.” His assertion was confirmed by examinations of the cerebral cortex of postmortem subjects, which showed that, of the six layers present, two showed more neurons per unit volume in females than in males: with these findings, neuroscientists can now explore whether or not these differences correlate with differences in cognitive abilities. The third is the decisive advancement made by G. M. Edelman,14 the Nobel prize winner for Philosophy and Medicine, who stated that what we know until now demonstrates that “the brain is the organ of consciousness”; indeed “that every cognitive task involves the activation or the distillation of many large parts of the brain,” and that “memory is the essential component of the brain mechanisms that generate consciousness.” Moreover, “with the attainment of language,”15 a consciousness of a higher order emerged in humans, followed in turn by thought, which came to light and is kept alive in all its splendor and remarkable complexity.” 16 It was natural selection that, over the course of a long period of evolution, gave rise to this being, Man, whose thoughts arise from the structure and interactions of his body. The mind flows from the body and from its development; it is rooted in the body and therefore belongs to its nature.

(Study by Leonardo da Vinci)The brain does not think, but as N. Chomsky emphasized, it readies “the physical realization of mental life.”17 Essential to this process are the architecture and activities of the cerebral neocortex, whose function in man it is to execute motor tasks, such as the muscular skeletal and eye movements, the expression of emotion, and the use of words. Indeed, the anterior part of the cerebral cortex, called the prefrontal cortex, increases in size as evolutionary development progresses: it is 3.5% in cats, 7.5% in dogs, 10.5% in monkeys and approximately 30% in man: the latter figure suggests the physiological importance of an ordered and active mental development proper to the human species that is vastly superior to what occurs in the brain development of the most advanced primates, which – as the extensive work of E. S. Savage-Rumbaugh18 demonstrates – failed to learn to pronounce 250 words, even in an unconnected manner, after many years of continual contact with their keepers.

(Study by Leonardo da Vinci)The brain does not think, but as N. Chomsky emphasized, it readies “the physical realization of mental life.”17 Essential to this process are the architecture and activities of the cerebral neocortex, whose function in man it is to execute motor tasks, such as the muscular skeletal and eye movements, the expression of emotion, and the use of words. Indeed, the anterior part of the cerebral cortex, called the prefrontal cortex, increases in size as evolutionary development progresses: it is 3.5% in cats, 7.5% in dogs, 10.5% in monkeys and approximately 30% in man: the latter figure suggests the physiological importance of an ordered and active mental development proper to the human species that is vastly superior to what occurs in the brain development of the most advanced primates, which – as the extensive work of E. S. Savage-Rumbaugh18 demonstrates – failed to learn to pronounce 250 words, even in an unconnected manner, after many years of continual contact with their keepers.

These brief comments on the achievements of neuroscience, which is in continual and rapid development, clearly demonstrate that the human brain is an extraordinary instrument composed of parts that are formed, developed and arranged in accord with a plan written into the DNA proper to each individual: a plan and program that is gradually realized through the subject’s growth and development. Yet careful examination shows that this wonderfully complex structure that constitutes the brain, the central and essential organ of the human person, is a highly perfected instrument that receives, records, and stores; but, as we have said, we are still unable to understand how the mind and the brain relate.

The enigma of the mind

The well known researcher Francis Crick, in his forward to the volume by Christof Kock19 – an excellent and out of the ordinary book – clearly points out regarding the voice of consciousness “that it is the main unresolved question in biology.”. This observation is correct, for consciousness –is “the presence of the mind to itself in the act of apprehending and of judging what is currently present to the mind.” But the mind is not a biological structure. Francis Crick and Christof Kock boldly conclude: “We live in a unique moment in the history of science. It is easily within technology’s reach to discover and characterize how the subjective mind arises from the objective brain. The coming years will be decisive.”

An immediate question arises: how can thought, which is the expression of a subjective mind, arise from an objective brain, which is finite in its biological structure? In reality, careful examination shows that this wonderfully complex structure that constitutes the brain, the central and essential organ of the human person, is a highly perfected instrument that receives, records, and stores; however, as W. R. Stoeger20 observes, the need and presence of an energy called “mind” clearly emerges.

Faced with the revelation of the wonderful structures of the human brain, which develop gradually as an indispensable instrument that enables the human person to elaborate and express the fruit of his mind, and to choose and execute his own decisions, we cannot but perceive the enjoyment of a privilege particularly reserved to the species Homo sapiens. C. M. Streeter, who proposed an anthropological vision of neuroscience, rightly stated: “The brain is not the mind. The brain is the mind’s physiological infrastructure. […] [We] have, perhaps for the first time, a modest beginning account of what empirical functions belong properly to the human spirit, as we have had from science the continually unfolding discovery of the functions of the brain.”21

In fact, mind and conscience are two essential, characteristic features that clearly separate the species “Man” from the rest of the animal world. In reality, the enigma of the mind and consciousness, which are exclusive to the human species, is resolved and at a level vastly superior to the strictly biological, which serves all the same as its indispensible basis. With keen observation, G. Buzsaki – in a careful and comprehensive volume on the human brain, acknowledges its greatness and personal importance with these clear and simple words: “The human brain is the most complicated mechanism ever created in nature. […] The hope is that the new knowledge about the brain will … provide a better understanding of ourselves.”22